A scientist on the great responsibility of using ancient DNA to rewrite human history0

- From Around the Web, Science & Technology

- April 6, 2021

There are ethical and methodological pitfalls to avoid.

There are ethical and methodological pitfalls to avoid.

To reach the Mariana Islands in the Western Pacific, humans crossed more than 2,000 kilometers of open ocean, and around 2,000 years earlier than any other sea travel over an equally long distance. They settled in the Marianas around 3,500 years ago, slightly earlier than the initial settlement of Polynesia.

For today’s Buddhist monks, Baishiya Karst Cave, 3200 meters high on the Tibetan Plateau, is holy. For ancient Denisovans, extinct hominins known only from DNA, teeth, and bits of bone found in another cave 2800 kilometers away in Siberia, it was a home.

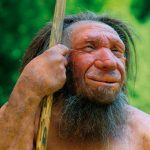

Study seeks to compare microbiomes of our ancestors for clues to modern diseases

The genomes of our closest relatives, Neanderthals and Denisovans, have been sequenced and compared with that of modern humans. However, most archaic individuals with high-quality sequences available have been female. In new research, a team of geneticists from the United States, China and Europe has sequenced the paternally inherited Y chromosomes from three Neanderthals and two Denisovans; comparisons with archaic and modern human Y chromosomes indicated that, similar to the maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), the human and Neanderthal Y chromosomes were more closely related to each other compared with the Denisovan Y chromosome; this result supports the conclusion that interbreeding between early Homo sapiens and Neanderthals replaced the more ancient Denisovian-like Y chromosome and mitochondria in Neanderthals.

In the public imagination, the Vikings were closely-related clans of Scandinavians who marauded their way across Europe, but new genetic analysis paints a more complicated picture.

When did something like us first appear on the planet? It turns out there’s remarkably little agreement on this question.

For tens of thousands of years, a Neanderthal molar rested in a shallow grave on the floor of the Stajnia Cave in what is now Poland. For all that time, viable mitochondrial DNA remained locked inside – and now, finally, scientists are discovering its secrets.

Darwin would be delighted by the story his successors have revealed

Synthetic DNA nanovaccines enhance killer T cell immunity resulting in tumor control in preclinical studies