Tiny traces of DNA found in cave dust may unlock secret life of Neanderthals0

- Ancient Archeology, From Around the Web

- May 18, 2021

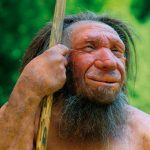

Advanced technique used to recover genetic material may help solve the mystery of early humans

Advanced technique used to recover genetic material may help solve the mystery of early humans

There are ethical and methodological pitfalls to avoid.

To reach the Mariana Islands in the Western Pacific, humans crossed more than 2,000 kilometers of open ocean, and around 2,000 years earlier than any other sea travel over an equally long distance. They settled in the Marianas around 3,500 years ago, slightly earlier than the initial settlement of Polynesia.

For today’s Buddhist monks, Baishiya Karst Cave, 3200 meters high on the Tibetan Plateau, is holy. For ancient Denisovans, extinct hominins known only from DNA, teeth, and bits of bone found in another cave 2800 kilometers away in Siberia, it was a home.

Study seeks to compare microbiomes of our ancestors for clues to modern diseases

The genomes of our closest relatives, Neanderthals and Denisovans, have been sequenced and compared with that of modern humans. However, most archaic individuals with high-quality sequences available have been female. In new research, a team of geneticists from the United States, China and Europe has sequenced the paternally inherited Y chromosomes from three Neanderthals and two Denisovans; comparisons with archaic and modern human Y chromosomes indicated that, similar to the maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), the human and Neanderthal Y chromosomes were more closely related to each other compared with the Denisovan Y chromosome; this result supports the conclusion that interbreeding between early Homo sapiens and Neanderthals replaced the more ancient Denisovian-like Y chromosome and mitochondria in Neanderthals.

In the public imagination, the Vikings were closely-related clans of Scandinavians who marauded their way across Europe, but new genetic analysis paints a more complicated picture.

Today’s humans carry the genes of an ancient, unknown ancestor, left there by hominin species intermingling perhaps a million years ago.

Genetic information from an 800,000-year-old human fossil has been retrieved for the first time. The results from the University of Copenhagen shed light on one of the branching points in the human family tree, reaching much further back in time than previously possible.

In the 1980s, paleontologists found a dinosaur nesting ground with dozens of nestlings in northern Montana and identified them as Hypacrosaurus stebingeri, a species of herbivorous duck-billed dinosaur that lived some 75 million years ago (Cretaceous period). Now, a team of researchers from the United States, Canada, and China has investigated molecular preservation of calcified cartilage in one of the Hypacrosaurus stebingeri nestlings at the extracellular, cellular and intracellular levels. They’ve found chemical markers of DNA, preserved fragments of proteins and chromosomes in the dinosaur chondrocytes (cartilage cells). The findings further support the idea that these original molecules can persist for tens of millions of years.