Scientists get hands dirty with research into medieval poop0

- Ancient Archeology, From Around the Web

- October 10, 2020

Study seeks to compare microbiomes of our ancestors for clues to modern diseases

Study seeks to compare microbiomes of our ancestors for clues to modern diseases

Archaeologists have uncovered evidence of an Iron Age massacre, frozen in time for thousands of years until excavation.

The genomes of our closest relatives, Neanderthals and Denisovans, have been sequenced and compared with that of modern humans. However, most archaic individuals with high-quality sequences available have been female. In new research, a team of geneticists from the United States, China and Europe has sequenced the paternally inherited Y chromosomes from three Neanderthals and two Denisovans; comparisons with archaic and modern human Y chromosomes indicated that, similar to the maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), the human and Neanderthal Y chromosomes were more closely related to each other compared with the Denisovan Y chromosome; this result supports the conclusion that interbreeding between early Homo sapiens and Neanderthals replaced the more ancient Denisovian-like Y chromosome and mitochondria in Neanderthals.

Roughly 80 million years ago in the shallow inland sea that once split North America into eastern and western land masses, a fearsome 10-meter-long (33-foot-long) marine reptile with powerful jaws and tremendous bite-force was one of the apex predators.

New bioarchaeology research from a University of Otago Ph.D. candidate has shown how infectious diseases may have spread 4000 years ago, while highlighting the dangers of letting such diseases run rife.

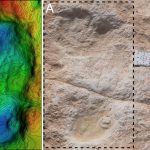

One day about 120,000 years ago, a few humans wandered along the shore of an ancient lake in what is now the Nefud Desert in Saudi Arabia. They may have paused for a drink of fresh water or to track herds of elephants, wild asses, and camels that were trampling the mudflats. Within hours of passing through, the humans’ and animals’ footprints dried out and eventually fossilized.

In the public imagination, the Vikings were closely-related clans of Scandinavians who marauded their way across Europe, but new genetic analysis paints a more complicated picture.

One of Germany’s most famous ancient artifacts may not be what it seems, if a new study is to be believed.

When did something like us first appear on the planet? It turns out there’s remarkably little agreement on this question.

For tens of thousands of years, a Neanderthal molar rested in a shallow grave on the floor of the Stajnia Cave in what is now Poland. For all that time, viable mitochondrial DNA remained locked inside – and now, finally, scientists are discovering its secrets.