As far as Shirkey’s concerned, his inexplicable departure from Roswell “was part of the cover-up” of the saucer crash.

Roswell Army Air Field Master Sergeant Robert Porter, a flight engineer in 1947, states that he flew wreckage from a UFO from Roswell to Carswell Air Force Base in Fort Worth, Texas, following the Roswell UFO Crash in July 1947.

Robert Shirkey Interview:

509th Bomb Group operations officer Robert Shirkey first learned that something unusual was being flown to Fort Worth when he returned from lunch July 8, 1947 and wonders if his interest in it caused him to be transferred unexpectedly to a non-existent job days later.

“I entered the Operations building and asked the civilian clerk on duty what was going on and he said, `We just got an order from Col. Blanchard to have a B-29 go to Fort Worth.’

“I walked out towards the ramp on the south side of the building and watched the B-29 pull up by the building and shut its engines off.

“I walked back in to (say) the plane was there and a voice behind me said, “Where’s my airplane?’ and it was Col. Blanchard who had come in through the front door. He stepped back into the hallway and waved at several people who were standing outside. They came into the front door and down the hallway and Blanchard stepped back into the doorway.

“I said to him, `Colonel, turn sideways I want to see too.’ Of course he gave me his usual scowl and we stood belt buckle-to-belt buckle with our heads turned, watching these people go through the hallway carrying boxes of this material they picked up.

“Maj. Marcel came along with an open cardboard box with several pieces of this aluminum-like material with one of the I-beams sticking up in the corner…with characters written on a portion of it. What the characters were I cannot recall at all.

“Another gentleman in a civilian suit was walking along with a piece stuck under his arm like a poster board.”

“The group went out on the ramp and across to the airplane. Col. Blanchard and I watched them hand the boxes up through the wheel well and they climbed the ladder and shut the door.”

At the same time a staff car came up to the back end of the airplane and was handing some boxes up to the rear door. It left and the aircraft started up its engines and taxied over to the runway and we stood there until we saw it leave the ground and start its turn toward Fort Worth.”

Shirkey said the debris that he saw loaded aboard the bomber looked nothing like weather balloons he saw launched from the weather building located near his own office at Roswell Army Airfield.

Shortly after this event, Shirkey, who was awaiting promotion to captain and assignment to a new job at Roswell air base, shortly afterward received some startling news.

“Nine days later I got a telegram from the Eighth Air Force sending me to Clark Field in the Philippines to fill the request the 13th Air Force had made for a weights and balance officer,” said Shirkey.

His orders, oddly enough, were signed by Brig. Gen. Roger Ramey, the Eighth Air Force commander who ordered Marcel to pose next to the debris that Marcel said was not what he had recovered.

If Shirkey felt he was being shuffled away from Roswell unceremoniously he found himself receiving unusually grand treatment in the way he was to fly to Hamilton Field, Calif., on the way to the Far East.

Deputy Base Commander Lt. Col. Payne Jennings, who flew the B-29 with the debris aboard to Fort Worth, informed Shirkey that he would personally fly him to California for his next assignment.

“He told me, `Take a few says off and next Sunday give me a call and I’ll take you to California.’

“A week or two later, Lt. Col. Payne Jennings – the deputy base commander – flew me as a first lieutenant to my next station in California before going overseas.

“As we were flying along at altitude I asked him why are you making this flight colonel and he said, `Just to take you to your next base.’

“When was the last time you heard of a first lieutenant being taxied by a deputy base commander in a B-29 to his next station?” asked Shirkey.

When he arrived at Clark Field in the Philippines he had another surprise when he was informed that no such job vacancy existed.

Shirkey was told the 13th Air Force had a weights and balance officer and didn’t need one. He would instead be made assistant operations officer in a photo reconnaissance unit.

As far as Shirkey’s concerned, his inexplicable departure from Roswell “was part of the cover-up” of the saucer crash.

Today, Shirkey teaches oil field safety techniques at a junior college branch of Eastern New Mexico University located on the grounds of the former Roswell Army Airfield.

Nearby is the one-time operations center, where Shirkey worked. It is today used by an aviation firm.

~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~

Walter Haut Interview:

On July 8, 1947 Walter Haut found himself at the epicenter of the most sensational and shortest news flap of his career as an Army Air Force public relations officer.

I got a call around 10:30 a.m. from Col. Blanchard’s office saying he wanted to see me so I immediately drove over to base headquarters and went into to see him,” said Haut, 75.

“He told me that he wanted me to put out a press release and take it to town and hand-deliver it to the news media.

“He told me exactly what he wanted in the press release — in essence that we had in our possession a flying saucer that had crashed north of town and that Maj. (Jesse) Marcel, our intelligence officer, had flown the material to Fort Worth.

“I did not ask him (Blanchard) any questions,” said Haut.

“This was the 509th bomb group which was a very secretive organization. (Even) I could not get close to an airplane that had the configuration to carry an atomic bomb in its bomb bay.

“At that point in time if you needed to know they told you. If you wanted to know — don’t ask — or you might end up being transferred to a nice place like Thule (Greenland).”

“I did exactly what he told me and delivered it to two newspapers and a radio station. I came home and had lunch. I went back to the base and the phone was ringing. The enlisted personnel said it had been ringing like mad.

“I picked up (the phone) and they wanted to know primarily how Maj. Marcel knew how to fly the object,” laughed Haut.

The release was worded in such a that it made it sound like Marcel had flown the mystery craft to Eighth Air Force Headquarters. Haut explained to reporters that only fragments of the craft were flown aboard a plane to Fort Worth.

“We were through with it (the saucer story) when I put out that release,” he said. “When (Brig.) Gen. (Roger) Ramey came out with the statement that it was not a flying saucer, that killed it.”

Ramey was commander of the Eighth Air Force at Fort Worth Army Airfield at the time and oversaw the new and improved explanation of what the rancher William “Mac” Brazel had discovered.

“It (the story) died a quick and sudden death,” said Haut who was then exposed to some ribbing by his colleagues.

“Some of my fellow officers said you sure blew that one didn’t you? I said, `Not me! It was the boss!'”

Except for one, side comment, Blanchard said nothing at all to Haut about what had happened.

The Monday following the (issuance of the now-famous) press release we were in a staff meeting,” said Haut. “I happened to be sitting close to him in the chair at the end of the table and he leaned over to me and said, `We sure blew that one didn’t we?'”

“We never talked about it. I never asked him and he never told me.”

Blanchard was based again at Roswell from 1951-1953 allowing the two to continue their friendship over occasional luncheon and dinner meetings.

During this period Haut would occasionally serve as base public relations officer at Blanchard’s request.

One extremely odd circumstance continued for years after the 1947 flying saucer episode in the form of visits that Haut and his wife “Pete” received over the years from an Air Force intelligence officer Haut knew from his days in the service.

“Anytime there was a flap over UFO sightings in the news anywhere in the country he would show up,” said Mrs. Haut still irritated by the visits.

“He would always say he had some business at the base and he wanted to come by for a visit and he would spend a lot of time talking about how the Air Force had explained away this UFO sighting or that one.”

“I really got tired of it,” she said.

Haut said visits eventually stopped and a UFO researcher inquired about the intelligence officer only to be told curtly by the Pentagon that the man had died.

Today, Haut is distressed by those who don’t take the mystery of the Roswell incident seriously by either debunking the event or by embellishing stories about what happened.

“People are trying to make a farce out of it” said Haut. “The people I know who were in a position to see and handle the material were not a bunch of weirdos seeking any sort of notoriety.

He recalled the then-Maj. Jesse Marcel as a capable and professional officer who lived two blocks from his own home. The two would occasionally drive to work together.

“Based on the fact they were in the 509th, their attitude was different than (that of) the normal personnel. When you handle atomic weapons you didn’t go around flipping out about this, that or the next thing.

To this day, Haut believes that what Blanchard told him was something that his commander absolutely believed. The press release, said Haut, is something that described precisely what happened.

The events surrounding Blanchard’s announcement about the recovery of a space craft apparently had no impact on Blanchard’s career since he attained the rank of general at the age of 40 and four-star rank at 50.

The official debunking of Blanchard’s announcement about flying discs was “orchestrated” by higher headquarters and acquiesced to by Blanchard, the quintessential professional soldier, believes Haut.

And what does Haut believe was found in the hills south of Corona?

“A vehicle of some sort, probably coming from outer space,” said the retired insurance man. “Or, perhaps some foreign country may have had an (aircraft) that crashed, but I don’t think that’s feasible.”

“I sincerely do not think in my lifetime or your lifetime that they (the Air Force) will come out with anything new (on this). I think they’ve had egg on their face for so long there’s no way they can wipe it off.”

~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~

COL. William “Butch” Blanchard

Col. William “Butch” Blanchard was commander of the 509th Bomb Wing at Roswell Army Airfield during the now-famous discovery of the mysterious wreckage near Corona, N.M.

The extraordinary career of the highly-decorated West Point graduate — who rose to the top of the ranks before his death at 50 — made it seem that Blanchard would know the difference between a balloon and an alien space craft.

Born in 1916 to a physician and his wife, Blanchard would ultimately rise to four-star rank in the United States Air Force before dying suddenly in 1966 of a heart attack at the Pentagon.

During World War II, he commanded the 58th Bomb Wing in the China-Burma-India Theater. In 1944 he flew the first B-29 into China from India to begin bombing operations against Japanese Army forces. He later commanded strategic bombing missions against Japan from the Marianas Islands.

It was during the war that Blanchard began a close professional and personal relationship with B-29 navigator Walter Haut who would later become his public relations officer at Roswell Army Air Field.

It was to Haut that Blanchard would dictate the announcement that a space craft had been recovered by the Air Force.

As commander of the 509th Bomb Wing, Blanchard oversaw the only U.S. military unit capable of delivering America’s then-small arsenal of nuclear weapons. He would later command the bomb wing during its participation in live nuclear weapon tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands.

A tall man, Blanchard was a perfectionist and a demanding leader. Those who served under him remembered he could turn steely cold if he found something done improperly.

Haut recalls that Blanchard would sometimes interrogate subordinate staff officers mercilessly to test their knowledge and get to the absolute bottom of a problem.

Those beneath him learned to obey him instantly and completely.

When Blanchard called Haut into his office and dictated to him the press release about the discovery of a “flying disc”, Haut took the information down, repeated it to Blanchard for confirmation and issued it to local news organizations.

That was the way you did business with Col. Blanchard, said Haut. If Blanchard said it, it was the gospel.

“He was a good guy,” Haut says of Blanchard. “But you never crossed him. He didn’t put up with foolishness. With him it was `do it and do it right’.

“I think he was a hand’s-on officer. He knew what was going on on the base. He would ask questions of all his squadron commanders and provost marshals I remember at staff meetings he would almost grill someone (asking), “Why did you do it that way.”

“When he wanted information he wanted it then and he wanted it accurately.”

“He was a very fine officer,” said Haut whose relationship with Blanchard ran so deep that when his former superior died in 1966, Blanchard’s widow requested that Haut be notified before any public announcement was made.

Haut, who lives in Roswell where he ran his own insurance business, recalled his surprise when a uniformed colonel came to his home to inform him of Blanchard’s death.

~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~

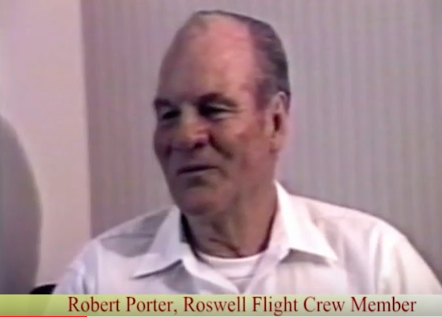

B-29 Flight Engineer Robert Porter Interview:

New Mexico native Army Air Force flight engineer Robert Porter knew nothing of his sister Loretta Proctor being asked by William “Mac” Brazel to look at a piece of unusual debris when he was asked to help fly the wreckage to Fort Worth on July 8, 1947.

Retired from the Air Force and now living in Great Falls, Mt., Porter remembers being told to man a B-29 carrying the wreckage to Eighth Air Force headquarters in Fort Worth.

The 76-year-old Porter said he’d heard nothing about the so-called saucer crash when he was ordered to man a B-29 bomber for a flight to Wright Field, Ohio with a stop at Fort Worth.

“They handed it (the debris) through the hatch,” he recalled. It was real light and wrapped in brown wrapping paper and taped.”

“There wasn’t more than about four or five pieces of it and one triangular piece about 18 inches across by two feet and the rest was in boxes like shoe boxes.”

Porter said he and his fellow crew members stayed on the field until the material was unexpectedly transferred to a smaller B-25 bomber that flew on to Wright Field.

“We just turned around and went back to Roswell,” said Porter.

Porter said that shortly after the flight he and his sister discussed what Brazel had shown her and they decided that it must have been what he and his fellow crew members flew to Fort Worth.

Porter also knew Brazel, describing him as a “quiet” man. “You could believe anything he said.”

Shared by Elizabeth Trutwin

Video source: Noe Torres

3 comments

3 Comments

Roswell UFO And Alien Corpses Were Stored Inside Top-Secret Hangar 18 At Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Whistleblowers Claim [Video]

September 6, 2016, 2:28 pm[…] Robert Porter claimed to have flown the UFO wreckage to Texas, according to Earth Mystery […]

REPLYRoswell UFO And Alien Corpses Were Stored Inside Top-Secret Hangar 18 At Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Whistleblowers Claim [Video] -

September 6, 2016, 2:31 pm[…] Robert Porter claimed to have flown the UFO wreckage to Texas, according to Earth Mystery […]

REPLY#Roswell-Zwischenfall: #UFO-Wrack und Aliens in Hangar 18 gelagert? » Mysteryblog

September 24, 2016, 12:01 pm[…] Robert Porter habe das Wrack des Roswell-UFOs nach Texas geflogen, berichtete Earth Mystery News. Laut den Aussagen von Lt. Robert Shirkey und Sgt. Robert Smith hätten sie dabei geholfen, […]

REPLY