A new study’s “treasure map” suggests that a planet several times more massive than Earth could be hiding in our solar system, camouflaged by the bright strip of stars that make up the Milky Way.

Source: awsforwp.com

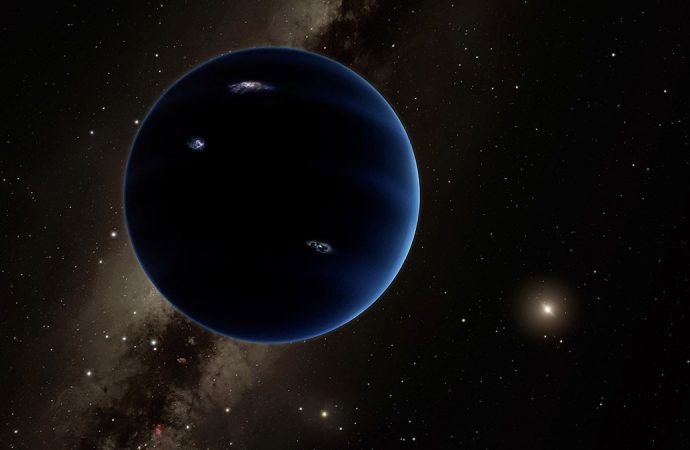

One of the more intriguing mysteries of the solar system is whether a large, icy planet lives in the outer reaches of our cosmic environment, far beyond Neptune’s orbit. Nicknamed “Planet Nine” by some scientists who search for it, this hypothetical world has sparked controversy since it was first proposed.

The invisible planet is predicted to exist based on the apparent influence of gravity on a group of small objects with strange, clustered orbits. But so far, searches for it have come up blank, and critics argue that the hints of its presence are just ghosts in the data.

Now, a new analysis predicts that if it’s out there, that creeping planet could be closer, brighter and easier to spot than previously estimated.

Instead of orbiting our home star once every 18,500 years, astronomers calculate that it orbits the sun in about 7,400 years. That tighter orbit brings it much closer to the sun than previously expected, meaning Planet Nine may appear brighter to telescopes on Earth.

“I think it will be found in a year or two,” said Mike Brown, an astronomer at the California Institute of Technology and an author of the new study, which has been accepted for publication in the Astronomical magazine. But, he adds, “I’ve made that statement every year for the past five years. I am super optimistic.”

Brown’s latest analyzes of Planet Nine’s gravitational shenanigans, calculated with his Caltech colleague Konstantin Batygin, suggest the world is about six times as massive as Earth — which would likely give him a rocky super-Earth or a gaseous mini-Neptune. to make. If discovered, the planet would be the first major world to join the solar system’s cast of characters since 1846, when astronomers announced the discovery of Neptune — an ice giant whose presence was predicted by its gravitational influence on Uranus.

But over the years, skeptics have suggested that the gravitational signatures that betray the presence of Planet Nine are nothing more than observational artifacts. The apparent clustering of the orbits of distant objects does not reflect the influence of an invisible world, critics argue, and is instead the result of natural biases in aerial surveys.

“Most of these objects are discovered with large telescopes that have little time for exploration of the outer solar system, and they look where they can look, depending on where they are,” said Renu Malhotra of the University of Arizona. who is agnostic about the existence of the planet and works on her own estimates of her position. Astronomers have discovered only a handful of these distant objects so far, and without a more complete count of the outer solar system, it’s hard to say whether these tiny, icy objects are really acting strangely or scattered randomly.

To help searchers in the meantime, Brown and Batygin used their revised calculations to create a “treasure map” that points to a patch of sky most likely to find Planet Nine. That region traverses the Milky Way’s densely populated, sparkling plane, which could have helped the planet hide during previous searches.

“Now we really know where to look and where not to look,” Brown says. “This should do it — unless we’ve done something wrong.”

Ghost Planets in the Distant Solar System

Brown and Batygin originally released their prediction of Planet Nine in 2016, but the pair aren’t the first to suggest an undiscovered world hides in the backcountry of the solar system. For more than a century, astronomers have mused about such a planet, mistakenly assuming that something significant is interfering with Neptune’s orbit. Astronomer Percival Lowell named the world Planet X and was so determined to find it that he left a million dollars to fund the ongoing search after his death in 1916. (In 1930, Clyde Tombaugh of the Lowell Observatory found tiny Pluto instead. .)

The Caltech team based their prediction of Planet Nine’s existence on how it apparently disrupts a group of Kuiper Belt Objects, or KBOs. These small, icy worlds beyond Neptune contain a population of objects with extreme orbits that take them at least 150 times further from the sun than Earth’s orbit.

In 2016, Batygin and Brown examined six such objects, whose elongated, tilted orbits have puzzled scientists for years. The team concluded that an invisible planet, about 10 times the mass of Earth, must gravitate the objects into their catawampus orbits. The planet’s estimated mass is between Earth and Neptune, making it a kind of world that is found all over the galaxy, based on studies of planets orbiting other stars, but which is conspicuously absent from our own solar system.

Shortly after the announcement, however, astronomers began to cast doubt on the Planet Nine hypothesis. Chief among their concerns was that the peculiar clustering of jobs may not cluster at all. Instead, over the past five years, multiple teams using different data sets have repeatedly concluded that the evidence pointing to Planet Nine is nothing more than an observing artifact.

Perhaps Planet Nine is an apparition, its supposed gravity handiwork a false signature created by a small number of misleading data points. Astronomers are still working to resolve the controversy, and this latest analysis from Brown and Batygin is an attempt to do just that.

“Glad they made a detailed prediction and put it out there,” said Michele Bannister of the University of Canterbury, whose work challenged the Planet Nine hypothesis in 2017. “I’ll be really happy if this thing turns out to exist — it’s going to be a fun solar system to live in.”

Refine the search

Brown and Batygin based their latest predictions of Planet Nine’s size and orbit on a slightly different set of objects. Some of the original KBOs remain in their dataset, but the team added new ones and discarded any objects whose orbits appeared to be affected by Neptune’s gravity. In the end they worked with 11 KBOs.

“If you count Neptune’s, you blur your signal and you don’t know what’s going on,” Brown says.

The new study finds there’s a 99.6 percent chance that the peculiar orbital alignment of these objects is the work of an invisible planet and not random. That sounds pretty good, Malhotra says, but it means there’s a 1 in 250 chance that the alignments are a fluke — which is far greater than the 1 in 10,000 chance that Brown and Batygin published in 2016.

Still, Malhotra says the new analysis is an improvement on previous work, even if it’s based on a small number of objects. “It’s intriguing enough to watch, but it’s not convincing,” she says.

Batygin also ran a ton of simulations to predict the characteristics of whatever world those 11 orbits would make up, mainly its location and mass. The end result is the “treasure map” pointing to planet Nine’s orbit in the sky, though the team still has no idea where the planet might be on that path.

Though it’s now estimated to be smaller — about five or six times Earth’s mass instead of 10 — the planet is apparently closer too. This means Planet Nine should be brighter in the sky, although Brown points out that the planet’s estimated brightness is based on assumptions about its composition, which could be wrong.

The new predictions bring the hypothetical world more in line with a similar claim made by astronomers Chad Trujillo and Scott Sheppard. In 2014, that team reported the discovery of an object called 2012 VP113, which they jokingly named “Biden” after then-U.S. Vice President Joe Biden. They suggested that a distant world five times as massive as Earth could push Biden and several other distant objects into clustered orbits.

But despite the converging hypotheses, experts in the field are nowhere near a consensus on Planet Nine’s existence.

“Overall, it holds up surprisingly well for something that hasn’t been found yet,” said Greg Laughlin, an astronomer at Yale University. “I feel like there’s a strong and interesting case out there, but it’s like, why haven’t they found it? And where is it?”

Finding Planet Nine

The fact that scientists have not yet seen Planet Nine could indicate that if it exists, the world will be near the farthest reaches of its orbit, making it a faint, slow-moving target hiding in the starlight. . Brown and Batygin, plus Sheppard and Trujillo, use the powerful Subaru telescope atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii to hunt for the elusive planet. But even with the sharpest tools in astronomers’ arsenal, the quest is challenging.

With its probable brightness and orbit, planet nine clumsily blends into the glittering masses of background stars – a world adrift amid our galaxy’s milky streamer in the night sky.

“It’s bright enough and close enough and prominent enough that that’s really the only region where it can lurk undetected,” Laughlin says. “My feeling is that if it’s there, it’ll be pinned down pretty quickly.”

Searching starfields with Subaru isn’t the only way astronomers can pin the planet to the sky. Busy searching for planets orbiting other stars, NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) may spot Planet Nine as it scans areas encompassing the planet’s supposed orbit.

In 2019, astronomers suggested that smart computing could extract objects from the distant solar system from TESS observations — a technique that Laughlin and Malena Rice of Yale University are currently working on.

“I’m not putting a super high probability on this, but it’s certainly not impossible that TESS frames can reveal an object if it’s there,” says Laughlin. “Every so often something happens that’s so amazing it doesn’t normally happen.”

Many astronomers agree that planet hunters’ most likely chance of finding Planet Nine is the Vera Rubin Observatory, which is currently under construction atop a Chilean mountaintop. This 8.4-meter telescope with a huge field of view will photograph the entire visible sky every few nights. Beginning in 2023, the observatory will allow astronomers to track the movements of millions of celestial bodies, including space junk, asteroids, comets, spy telescopes, stars and perhaps even planet nine.

“Vera Rubin will cover about two-thirds of the sky, but it will cover that sky evenly and repeatedly,” says Malhotra. “It will really help us make great progress on these kinds of issues.”

Brown thinks the planet could show up before fancy next-generation telescopes come online — perhaps, he says, the nondescript world is lurking in data astronomers already have in hand.

“I bet — and I often lose bets — that images of it exist in surveys we already have,” Brown says. “I don’t think anything was discovered that wasn’t later found in existing data, starting with Uranus, all the way to Pluto and Eris.” Brown discovered the dwarf planet Eris in 2005 at the Palomar Observatory, and he later found that the earliest image of it on a photographic plate was taken by the same telescope in 1955. “I just have a feeling it’s going to happen again.”

Source: awsforwp.com

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.