It’s the first in nearly 10 years, and there are only two more transits in the next couple of decades.

A Guide to the Transit of Mercury on May 9, 2016

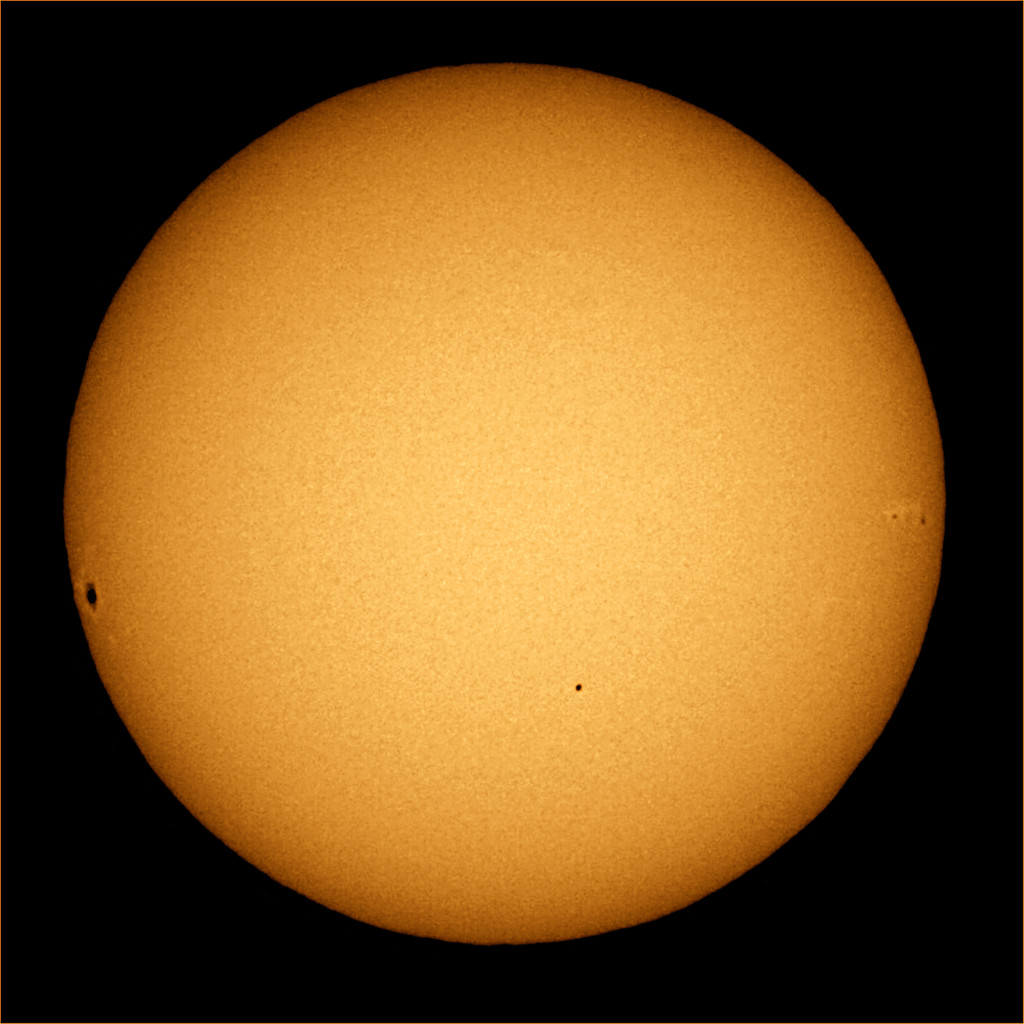

The disk of Mercury, below and right of the center of the Sun’s disk, during the transit of November 8, 2006. Credit: Brocken Inaglory through Wikipedia Commons.

The planet Mercury will appear to pass across the face of the Sun on Monday, May 9, 2016. This event, known as a transit, will be visible in a small telescope with a proper solar filter from much of North and South America, Africa, and western Europe. It’s a great opportunity to see the mechanics of the solar system in action and to spot the elusive inner planet as it passes across the blazing solar disk.

A Rare Celestial Event

Transits of Mercury are relatively rare. They occur just 13 to 14 times each century. The last transit of Mercury occurred on Nov. 8, 2006. The next two happen on Nov. 11, 2019 and Nov. 13, 2032. Venus, the only other planet to appear to transit the Sun as seen from Earth, does so far less frequently, only twice per century on average. The last two transits of Venus were on June 8, 2004 and June 5, 2012. The next pair occur more than a hundred years from now in 2117 and 2125. So if you want to see a transit of an inner planet in your lifetime, it’s going to have to be a transit of Mercury.

The May 9, 2016 transit of Mercury occurs over a 7.5 hour period from 11:12 Universal Time (UT) to 18:42 Universal Time. This handy online calculator converts Universal Time, which is essentially Greenwich Mean Time, to your own time zone. The exact timing depends very slightly on your location and can vary by a minute or two.

The projected path of Mercury across the disk of the Sun during the transit of May 9, 2016. Credit: Fred Espenak at EclipseWise.com

The transit begins as the leading edge of Mercury’s tiny disk just contacts the face of the Sun. Just 3 minutes and 12 seconds later, near 11:15 UT, the full disk of the planet becomes visible against the Sun. The point of greatest transit, when Mercury lies closest to the center of the Sun’s disk, occurs at 14:57 Universal Time. The leading edge of the planet moves off the Sun’s disk at 18:39 UT, then the trailing edge exits the disk, and the transit ends, at 18:42 UT. At greatest transit, the center of Mercury’s disk will be 318.5” from the center of the Sun’s disk. The diagram above from Fred Espenak at EclipseWise.com shows the path of the planet, the timing, and the celestial coordinates of the Sun and Mercury at greatest transit.

The timing of this transit of Mercury favors observers in eastern North America, most of South America, and western Europe. The full transit will be visible in these regions. In western North America, Chile, and Hawaii and much of the Pacific, the transit will be in progress as the Sun rises. In central Europe, western Asia, India, and Africa, the transit will be in progress as the Sun sets.

This transit is not visible from Australia or New Zealand.

Worldwide visibility of the transit of Mercury on May 9, 2016. Credit: Fred Espenak at EclipseWise.com.

How to Observe the Transit of Mercury

The disk of the Mercury is just 12” across, too small to see with your unaided eyes and a pair of eclipse glasses. The planet will have an apparent area just 3% that of Venus during its transits, for example, so it will be hard to distinguish Mercury from a small sunspot. You will need a telescope at a magnification of at least 50x to see or image the transit. And, of course, you will need a good solar filter to keep the brilliant light of the Sun to a safe level. At no time during the transit of Mercury is it safe to look towards the Sun or attempt to image the Sun without a proper solar filter.

Which solar filter works best for observing a transit? Both main types of solar filter– broadband or “white-light” solar filters and narrowband or “hydrogen-alpha” solar filters work just fine for visual observation and imaging.

If you find yourself without a solar filter, you can project the image from your telescope with your lowest-power eyepiece onto a sheet of white paper a couple of feet away. This projection method, which is recommended only for scopes with aperture 80mm or less, isn’t as effective as direct observation with a solar filter, but it should be sufficient to show Mercury’s disk during the transit. Take great care when using this method to ensure no one looks through the unfiltered telescope.

Timing the Transit of Mercury

Most backyard astronomers enjoy the transit of Mercury simply for pleasure. But keen observers can make a contribution to science by attempting to measure the precise timing of the transit from their location. ALPO (The Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers) has a program to study the transit. You can learn more at this link.

Whether your interests lie in observing and enjoyment or precise measurement and science, plan to have a look at the May 9, 2016 transit of Mercury. It’s the first in nearly 10 years, and there are only two more transits in the next couple of decades. So gear up and get ready to see the solar system in action.

Source: Cosmic Pursuits

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.