Marine plants and animals that cling to the pieces of pumice could help revive the Great Barrier Reef, scientists say.

Source: NBC News

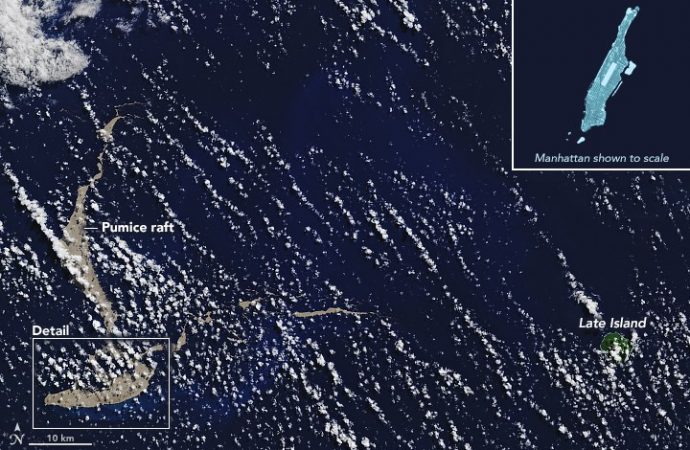

A huge raft of volcanic rock has been spotted in the Pacific Ocean, and the Manhattan-size mass appears to be drifting slowly toward Australia.

As it floats along, scientists said various marine plants and animals would populate the loose collection of light, porous rock — and that their arrival and dispersal Down Under could help revive portions of the Great Barrier Reef that have been damaged by pollution and the warmer, more acidic waters resulting from climate change.

The mass, which was spotted on Aug. 9 by NASA’s Terra satellite, is made up of an estimated 1 trillion bits of pumice ranging in size from marbles to basketballs. All of the material is believed to have come from the eruption of an underwater volcano near the island nation of Tonga in early August.

“If you think about the eruption like a bottle of Coke or Champagne, and you shake it up and take the lid off, there’s all that foam that comes out,” said Scott Bryan, a geologist at the Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia. “If we solidify that foam, that’s basically what pumice is when it cools and falls back down to the ocean.”

The brownish mass has a distinct odor, according to an Australian couple who sailed through it a few days after the satellite snapped images of it. “The rubble slick went as far as we could see in the moonlight and with our spotlight,” Michael and Larissa Hoult said in an Aug. 15 Facebook post, adding that they noticed a “faint but distinct smell of sulfur” as their catamaran navigated the floating rubble field.

Bryan said pumice eventually becomes water-logged and sinks but that rafts like the one spotted recently can persist for months or years. As they do, mollusks, anemones and other marine animals and plants start to occupy the nooks and crannies — and go along for the ride.

Since 2001, Bryan and his colleagues have studied pumice rafts formed by three separate underwater volcanic events. Each time, they reported that pieces of pumice were covered with living organisms. “There was an amazing diversity of marine plants and animals,” Bryan said. “Each pumice was an amazing ecosystem, like its own little community.”

Models of ocean currents and winds suggest that it will take the raft about a year to reach Australia’s eastern shore and the Great Barrier Reef, which in recent years has experienced a number of bleaching events in which coral die and turn a ghostly whitish color.

“These billions and billions of rock can carry corals, and in the best-case scenario, they spread these little corals through the Southwest Pacific and resettle on the Great Barrier Reef,” said Martin Jutzeler, a lecturer at the University of Tasmania, in Australia, and an expert on underwater volcanoes.

Even if only 0.1 percent of the pumice rocks deliver baby corals that successfully colonize the Great Barrier Reef, Bryan said, that could represent hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of new corals added to the imperiled reef.

“It’s certainly not a silver bullet, but it’s important to recognize that this is happening naturally and nature is a bit more interconnected than we assumed or understood in the past,” Bryan said. “But that doesn’t mean we don’t need to do anything” to protect the world’s coral reefs.

Jutzeler agreed, saying the only way to save the planet’s reefs is to address the root cause of coral bleaching: climate change. “This is a natural and easy way to replenish life on the Great Barrier Reef,” he said. “But if the climate continues to warm, bleaching events will occur again and this replacement of life will not last very long.”

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.