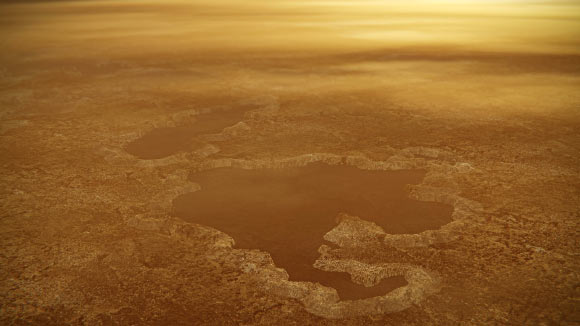

Small methane-filled lakes on the surface of Titan were likely formed by explosive, pressurized nitrogen just under the hazy moon’s surface, according to a new analysis of radar data from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft.

Source: Sci News

Most existing models that lay out the origin of Titan’s lakes show liquid methane dissolving the moon’s bedrock of ice and solid organic compounds, carving reservoirs that fill with the liquid.

This may be the origin of a type of lake on Titan that has sharp boundaries. On Earth, bodies of water that formed similarly, by dissolving surrounding limestone, are known as karstic lakes.

The new, alternative model for some of the smaller lakes — tens of miles across — turns that theory upside down. It proposes pockets of liquid nitrogen in Titan’s crust warmed, turning into explosive gas that blew out craters, which then filled with liquid methane.

The new theory explains why some of the smaller lakes near Titan’s north pole appear in radar imaging to have very steep rims that tower above sea level — rims difficult to explain with the karstic model.

“The rim goes up, and the karst process works in the opposite way,” said Dr. Giuseppe Mitri, a researcher at the G. d’Annunzio University.

“We were not finding any explanation that fit with a karstic lake basin. In reality, the morphology was more consistent with an explosion crater, where the rim is formed by the ejected material from the crater interior. It’s totally a different process.”

This new study meshes with other Titan climate models showing the moon may be warm compared to how it was in earlier Titan ‘ice ages.’

Over the last half-billion or billion years on Titan, methane in its atmosphere has acted as a greenhouse gas, keeping the moon relatively warm — although still cold by Earth standards.

Planetary scientists have long believed that the moon has gone through epochs of cooling and warming, as methane is depleted by solar-driven chemistry and then resupplied.

“In the colder periods, nitrogen dominated the atmosphere, raining down and cycling through the icy crust to collect in pools just below the surface,” said Professor Jonathan Lunine, Cassini scientist from Cornell University.

“These lakes with steep edges, ramparts and raised rims would be a signpost of periods in Titan’s history when there was liquid nitrogen on the surface and in the crust.”

“Even localized warming would have been enough to turn the liquid nitrogen into vapor, cause it to expand quickly and blow out a crater.”

The study is published in the journal Nature Geosciences.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.