A prominent scholar and historian of Second Temple period Judaism revisits the tantalizing issues surrounding the almost forgotten “Abba Cave” tomb in Jerusalem.

Lost and almost forgotten over the years amidst the flurry of news about other archaeological discoveries in and around Jerusalem, the ‘Abba Cave’ is arguably still on the list of cold cases of ancient tomb discoveries of the last century. But recently, Dr. James Tabor, Professor of ancient Judaism and early Christianity at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte, has penned a few reminders about it in his popular blog, raising some issues that could be worth another look among scholars with the expertise and resources to investigate the case.

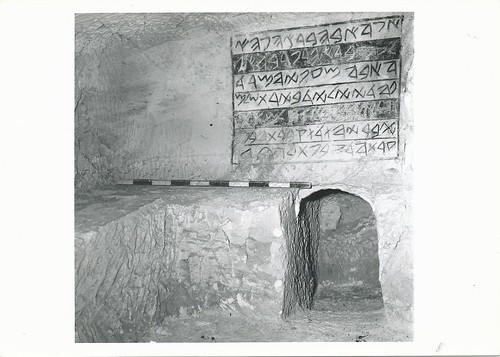

The story begins with a discovery in 1970 when construction workers stumbled across an ancient tomb while building a private home in the Givat Hamivtar community in East Jerusalem. Interestingly, the tomb was not far from another famous tomb excavated in 1968, also in Givat Hamivtar, that contained the 1st century CE bones of a crucified man named Yehohanan. But the 1970 tomb discovery, consisting of two chambers, was dated to the 1st century BCE. Within the tomb was an ornately engraved ossuary (a limestone bone box used by 1st century jews to collect and store the bones of deceased family members one year after death). On the tomb wall above the ossuary was an inscription in Aramaic:

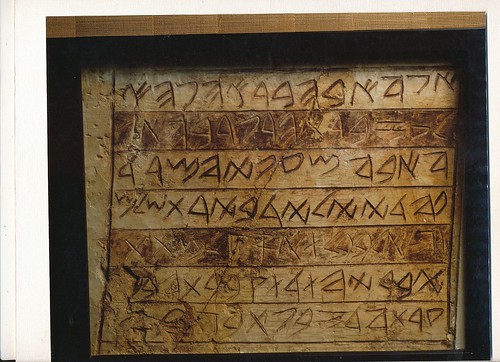

“I am Abba, son of Eleazar the priest. I am Abba, the oppressed, the persecuted, born in Jerusalem and exiled to Babylon, who brought back Mattathiah son of Judah and buried him in the cave that I purchased.”

Initial investigation and interpretation of the tomb and its contents in the 1970’s led scholars to suggest that the tomb contained the remains of Antigonus II Mattathias, the last king of the Hasmonean dynasty, the ruling Jewish family that was established when the Maccabean Revolt successfully threw off the yoke of the Seleucid Empire in the 2nd century BCE. Antigonus II, however, came to a horrific end when he was captured and executed by crucifixion and beheading at the hands of Marc Antony in 37 BCE after Jerusalem was captured and the throne seized by client king Herod (otherwise known as Herod the Great). The circumstances and evidence of the tomb and its contents were telling: The contents of Abba’s inscription on the wall; an elaborately decorated ossuary fit for a king; bones of a person 25 years old — including those of the hand with embedded nails and a cut jaw and cuts on the 2nd vertebra, indications of crucifixion and beheading—all osteological evidence that would be consistent with what is known about Mattathias; and the lack of an inscription on the ossuary identifying the remains, coupled with the finding that the ossuary was hidden in a niche under the floor of the cave — circumstances that could be consistent with someone securing the vanquished king’s remains during a time when the Hasmoneans were under persecution after the fall of Mattathias.

But later, other scholars disputed the interpretation. Most notable was the analysis of the bones by Patricia Smith of the Hebrew University. Smith concluded that the cut jaw belonged to an elderly woman, and that the nails found in the ossuary had not passed through the bones.

The case was ‘closed’ for years.

Until two experts began to re-examine the case.

The first expert was Yoel Elitzur, a Hebrew University historian and scholar of Semitic languages who in 2013 published a study that identified Abba, the name of the person who inscribed the message on the wall above the ossuary in the tomb, as the head of a family (according to Josephus) who were supporters of the Hasmoneans even after Herod had ascended to the throne.

The second expert was Israel Hershkovitz, a Tel Aviv University anthropologist, who re-examined the nails that were found within the ossuary using an electron microscope, and found that the nails did indeed penetrate the bones of the hand — driven through the palm and bent or hooked, presumably to keep the arms and hands secured on the cross beam of the cross. Moreover, says Hershkovitz, Smith’s earlier examination and conclusions regarding the gender of the bones were unconvincing, as the bones she examined would not securely identify the sex of the person. This is aside from the fact that, if she was correct, then the Romans crucified a woman, something that Hershkovitz maintained the Romans almost never did.

__________________________________________

The “Abba” tomb.

________________________________________________________

The “Abba” tomb inscription.

_______________________________________

The ossuary, in situ within the tomb.

___________________________________________________

The “Abba” ossuary, showing the ornate engravings on one side.

___________________________________________________

Tabor, for his part, favors a reconsideration of the original interpretation of the Abba tomb discovery. As he relates in his blog, he suggests the argument for the remains of a crucified and beheaded male in the tomb is still convincing. Taking all the facts together, “the hypothesis that this individual was the Hasmonean royal priest/king Antigonus,” writes Tabor, “turns out to be a live option.”

Source: Popular Archeology

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.