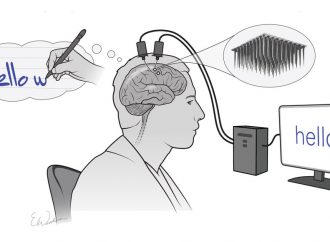

Ancient DNA from this skeleton, found in a Moroccan cave, is the oldest known from Africa.

About 15,000 years ago, in the oldest known cemetery in the world, people buried their dead in sitting positions with beads and animal horns, deep in a cave in what is now Morocco. These people were also found with small, sophisticated stone arrowheads and points, and 20th century archaeologists assumed they were part of an advanced European culture that had migrated across the Mediterranean Sea to North Africa. But now, their ancient DNA—the oldest ever obtained from Africans—shows that these people had no European ancestry. Instead, they were related to both Middle Easterners and sub-Saharan Africans, suggesting that more people were migrating in and out of North Africa than previously believed.

“The findings are really exciting,” says evolutionary geneticist Sarah Tishkoff of the University of Pennsylvania, who was not part of the work. One big surprise from the DNA, she says, is that it shows that “North Africa has been an important crossroads … for a lot longer than people thought.”

The origins of the ancient Moroccans, known as the Iberomaurusians because 20th century archaeologists thought they were connected to peoples of the Iberian Peninsula, have been a mystery ever since the Grotte des Pigeons cave was discovered near Oujda, Morocco, in 1908. Starting 22,000 or so years ago, these hunter-gatherers eschewed more primitive Middle Stone Age tools, such as larger blades used on spears, to produce microliths—small pointed bladelets that could be shot farther as projectile points or arrowheads. Similar tools show up earlier in Spain, France, and other parts of Europe, some associated with the famous Gravettian culture, known for its stone figurines of curvaceous women.

“The idea in the 1960s was that the Iberomaurusians must have got the microblades from the Gravettian,” says co-author and archaeologist Louise Humphrey of the Natural History Museum in London. During the ice age 20,000 years ago, sea level would have been lower and the Iberomaurusians were thought to have crossed the Mediterranean by boat at Gibraltar or Sicily.

Humphrey and her Moroccan colleagues got a chance to test this view after they discovered 14 individuals associated with Iberomaurusian artifacts at the back of the Grotte des Pigeons cave in 2005. Paleogeneticists Marieke van de Loosdrecht and Johannes Krause of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (SHH) in Jena, Germany, with Matthias Meyer of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, used state-of-the-art methods to extract DNA from the ear bones of skeletons that had lain undisturbed since they were buried about 15,000 years ago. That’s a major technical feat because ancient DNA degrades rapidly in warm climates; these samples are almost twice as old as any other DNA obtained from humans in Africa.

DNA in hand, Van de Loosdrecht and Choongwon Jeong, also of the SHH, were able to analyze genetic material from the cell’s nucleus in five people and the maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA from seven people. But they found no genetic tie to ancient Europeans. Instead, the ancient Iberomaurusians appear to be related to Middle Easterners and other Africans: They shared about two-thirds of their genetic ancestry with Natufians, hunter-gatherers who lived in the Middle East 14,500 to 11,000 years ago, and one-third with sub-Saharan Africans who were most closely related to today’s West Africans and the Hadza of Tanzania.

The Iberomaurusians lived before the Natufians, but they were not their direct ancestors: The Natufians lack DNA from Africa, Krause says. This suggests that both groups inherited their shared DNA from a larger population that lived in North Africa or the Middle East more than 15,000 years ago, the team reports today in Science.

As for the sub-Saharan DNA in the Iberomaurusian genome, the Iberomaurusians may have gotten it from migrants from the south who were their contemporaries. Or they may have inherited the DNA from much more ancient ancestors who brought it from the south but settled in North Africa where some of the earliest members of our species, Homo sapiens, have been found at Jebel Irhoud in Morocco.

All this offers the first glimpse of the deep history of North Africans, who today have a large amount of European DNA. It suggests that there were more migrations between North Africa, the Middle East, and sub-Saharan Africa than previously believed. “Cleary, human populations were interacting much more with groups from other, more distant areas than was previously assumed,” Krause says. Further studies will search for the people who gave rise to both the Iberomaurusians and the Natufians.

“It’s a thrill to look for the first time at ancient DNA from prehistoric peoples from North Africa, a place where repeated waves of migration have made reconstruction of the deep population history based on living populations almost impossible,” says population geneticist David Reich of Harvard University, who was not part of the team.

Source: Science Magazine

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.