Japan has lost contact with the newly-launched Hitomi space telescope, and ground observations indicate the satellite has shed debris and may be tumbling in orbit more than 350 miles above Earth.

Japan has lost contact with the newly-launched Hitomi space telescope, and ground observations indicate the satellite has shed debris and may be tumbling in orbit more than 350 miles above Earth.

Ground controllers lost contact with the Hitomi black hole observatory at the start of a planned communications pass around 0740 GMT (3:40 a.m. EDT) Sunday, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency said in a statement.

Shortly before the loss of communications with Hitomi, the U.S. military’s space tracking radars detected five objects in the vicinity of the satellite. The Joint Space Operations Center, the U.S. military command charged with monitoring objects in orbit, said Monday the debris came off the Hitomi spacecraft around 0142 GMT Sunday (9:42 p.m. EDT Saturday).

The Hitomi mission, also known as Astro-H, launched Feb. 17 aboard a Japanese H-2A rocket. The mission was supposed to last at least three years.

Engineers have been unable to determine the health of the satellite since the sudden disruption in communications, JAXA said, although ground controllers received a brief signal from Hitomi.

“While the cause of communication failure is under investigation, JAXA received short signal from the satellite, and is working for recovery,” the space agency said in a statement.

JAXA established an emergency response headquarters to investigate the satellite’s communications failure and attempt to recover the mission.

The detection of debris from Hitomi indicates an “energetic event” occurred aboard the satellite, according to Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who expertly tracks satellite activity.

But McDowell said it is too early to write Hitomi’s obituary, citing other space science missions that have come back from the brink of failure to resume normal operations, such as the NASA-ESA SOHO solar observatory.

“‘Debris’ doesn’t mean Hitomi’s in little pieces,” McDowell wrote on Twitter. “It means little pieces have come off it. Satellite might be basically intact, we don’t know.”

An explosion inside the Hitomi spacecraft, a fuel or gas leak, or a collision with a piece of space junk could have generated the debris and put the satellite in a tumble.

Hitomi was still in a functional testing phase when Sunday’s anomaly occurred. Normal science observations were supposed to begin later this year.

JAXA officials renamed the Astro-H mission Hitomi after launching last month. Hitomi means “eye” or “pupil” in Japanese.

Hitomi is Japan’s sixth X-ray astronomy satellite, following up on a series of missions since 1979 that resolved the universe’s most energetic regions.

X-rays emitted by hot plasma hold clues about the inner workings of the mysterious black holes, the lives of galaxies, the structure of galactic clusters and where clumps of dark matter may reside in the universe.

Formed by the powerful supernova explosions of old stars, black holes give off X-rays as they ingest matter, sending beams through the universe that can only be detected by telescopes like the sensors aboard Hitomi.

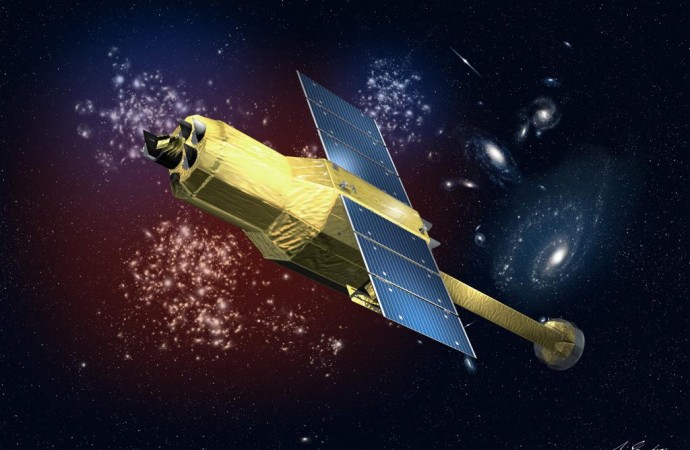

The Hitomi observatory extended a boom to a length of 20 feet — more than 6 meters — soon after its Feb. 17 launch. The deployable bench hosts the craft’s hard X-ray imagers, while the rest of the mission’s instruments reside in the satellite’s main body.

The mission’s core instrument is the Soft X-ray Spectrometer, or SXS, which contains a “microcalorimeter” developed jointly by Japanese and U.S. scientists. Chilled to 50 milliKelvin (minus 459.58 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 273.1 degrees Celsius), a fraction of a degree above absolute zero, the detectors were designed to register X-ray photons and measure their energy with high sensitivity, collecting data that will tell astronomers about the composition and velocity of the super-heated matter that produced the light.

Super-cold liquid helium and a series of mechanical and magnetic refrigerators were to keep a 36-pixel detector array chilled for at least three years, cold enough to sense faint light from faraway objects.

JAXA officials reported the SXS instrument’s microcalorimeter reached its super-cold operating temperature Feb. 22, allowing Hitomi’s three-month test and calibration campaign to start.

The microcalorimeter was to be the first sensor of its kind to make astronomical measurements in space. First developed in the 1980s, the technology was supposed to fly aboard a NASA observatory that eventually became Chandra, which launched in 1999, but cost concerns kept the sensor off the mission.

Earlier versions of the Soft X-ray Spectrometer launched on two Japanese X-ray missions in 2000 and 2005, but the first was destroyed in a launch failure, and the second ran into trouble weeks after liftoff and ran out of liquid helium coolant before observations began, rendering the instrument useless.

Scientists hoped for a better outcome this time.

Hitomi’s X-ray sensors were designed to see cosmic phenomena invisible to the human eye, seeing through veils of gas and dust that obscure observations with conventional telescopes.

Japan spent 31 billion yen, or about $270 million, on the Astro-H project, not counting contributions from the United States, Canada and Europe.

Source: Spaceflight Now

Image: JAXA/Akihiro Ikeshita

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.