Putting astronauts into short-term hibernation could make space travel more efficient.

If you’re a sci-fi movie aficionado, you may have heard of cryosleep. Heck, if you haven’t been living under a rock, you know last year’s blockbuster “Interstellar” gives it a starring role. As it turns out, it’s not just the stuff of fantasy anymore. At the end of last year, NASA, together with the Atlanta-based SpaceWorks Enterprises, unveiled plans to dramatically change the way we do space travel through the use of cryosleep.

Though technologically feasible, a mission to Mars has remained out of reach because of the cost and the sheer mass of the human load. In fact, human crew and all of the things that go along with us have a direct impact on mission mass, as well as number of launches required for the trip and complexity. Dr. Bobby Braun, former NASA chief technologist, said, “Anytime you introduce humans, it’s an order of magnitude or two more challenging.”

Scientists believe that they can resolve the problem through the use of torpor, or short-term hibernation, which is found to exist naturally among a number of mammalian species. By creating a torpor stasis habitat in which the space shuttle crew “hibernates” for much of their travel time, a space mission to Mars becomes more feasible. The researchers based their methodology on the use of induced hypothermia in medical situations. In fact, medically induced hypothermia is used to treat a variety of conditions, from neonatal encephalopathy to traumatic brain or spinal cord injury. It lowers a patient’s body temperature to help reduce the risk of ischemic injury to tissue after a period of insufficient blood flow.

Medically-induced hypothermia has only been used in critical patient care. Until now.

How it would work

Standard living quarters in a space shuttle would be replaced with a torpor habitat, in which the pressurized volume would be greatly decreased. The chamber would allow for six crew members to coexist in a torpor state simultaneously. A hypothermic state would likely be induced by cooling the body’s core temperature (induced in one of three ways), which would happen slowly over a few hours.

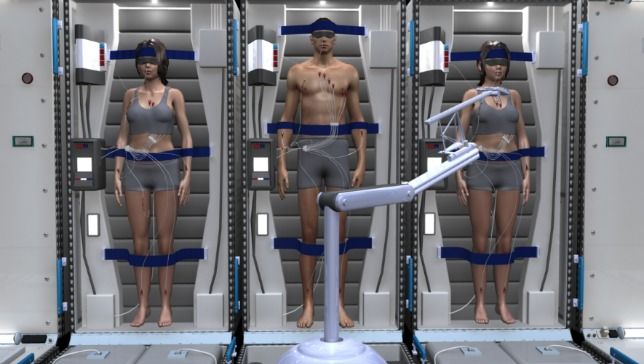

While the crew members are in a hypothermic state, various sensors would be hooked up to them so that their conditions could be monitored. They would receive nutrition intravenously through TPN — total parenteral nutrition. The liquid would contains all the essential elements for a human body to function. In addition, a catheter would be inserted to drain urine. Because no solids are consumed, the digestive system, and therefore the need for bowel function, would be inactive. Electromagnetic muscle stimulation would protect key muscle groups from atrophy.

The crew would be in this medically induced hypothermic state for 14 days at a time, with crew members taking turns being awake for two or three days at a time to ensure the needs of the crew and ship are met.

The benefits of this scenario? A major reduction in consumables due to an inactive crew, a dramatically lower pressurized volume required for living quarters, and the ability to eliminate things like a food galley, exercise equipment, entertainment, et cetera. Indeed, SpaceWorks says the mass of a shuttle with a crew in torpor would be 19.8 tons, less than half the mass of the reference habitat.

Sounds enticing — at least for those of us on the ground. Still, plenty more research needs to be done and many more questions remain to be answered, but the groundwork for turning the stuff of science fiction into a practical reality is there.

To find out more about the torpor stasis habitat, be sure to check out NASA and SpaceWorks’ full presentation.

Source: Mother Nature Network

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.