In 1526, the Spanish conquistador Francisco de Montejo arrived on the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico and found most of the great Maya cities deeply eroded and unoccupied. Many generations removed from the master builders, engineers, and scientists who conceived and built the cities, the remaining Maya they encountered had degenerated into waring groups who practiced blood rituals and human sacrifice.

The great city of Chichen Itza was reduced to piles of stones, with the vestiges of buildings, pyramids and other structures left in ruin. The Maya elders who I’ve spoken with report that Chichen Itza was a teaching university and that different cultures throughout the Americas had access to a variety of sciences, agricultural studies and the healing arts for hundreds or thousands of years. We still do not know the true age of the Maya, but recent excavations by Dr. Richard Hansen, at the El Mirador basin in Guatemala, show agriculture in that region flourishing around 2,600 BC—over 5,000 years ago.

Highly Advanced Sciences

We now know that the Maya developed a number of highly advanced sciences, highlighted by their spectacular knowledge of astronomy; they were skilled engineers, and had a mathematics which could calculate dates billions of years in the past and far into the future. It’s estimated that when Friar Diego de Landa discovered texts in buildings and in use by the surviving people, he burned them, and destroyed libraries, technical manuals and the history of one of the most advanced cultures on our planet, leaving us wondering at the history of the Maya.

El Caracol at Chichen Itza (Laurent de Walick /CC BY 2.0)

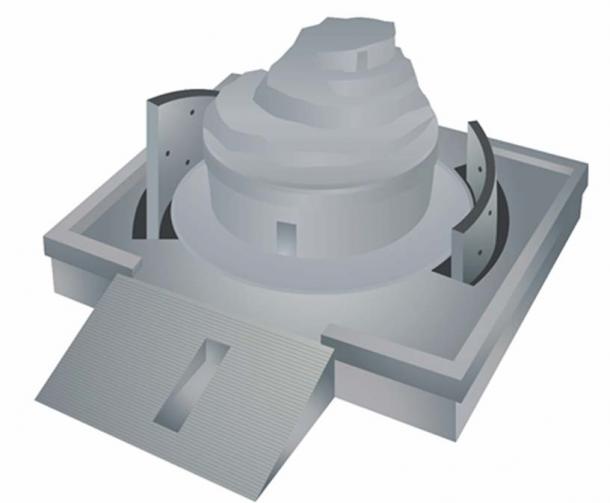

In 1913, Sylvanas Morley, an American archaeologist working with the Carnegie Institute, received permission by the Mexican government to excavate the main Acropolis at Chichen Itza. One of these buildings was the El Caracol, which he discovered was an astronomical observatory for charting the heavens.

![[Top] El Caracol as it appeared just before major excavation was started (MALER, 1892), and [Bottom] El Caracol as it is today (Kelly Lenfest, 2016/CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)](http://www.ancient-origins.net/sites/default/files/Caracol-as-it-appeared.jpg)

[Top] El Caracol as it appeared just before major excavation was started (MALER, 1892), and [Bottom] El Caracol as it is today (Kelly Lenfest, 2016/CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

As the excavation team began to reassemble the building, they encountered a number of advanced design features which could only have been incorporated after significant research and development and an understanding in correctly aligning the central observatory with the cosmos.

Through careful reconstruction and observation, we’ve made great strides in learning how the Maya used the observatory to chart the movement of specific planets, the beginning and conclusion of seasons, and other astronomical events.

Observing Space and Time

The El Caracol observatory stands on a massive 75 by 57-meter (246 by 246-foot) platform, engineered to support the tower and counter balance any movements in the Earth. To date, no surface penetrating radar has been used to detect what lies inside the platform, but it appears that a drainage system was incorporated to keep water from accumulating on the surface. The terrace, which connects the observatory to the platform, measures 26 by 30 meters (85 by 98 feet), and contains engineering features that function in a surprisingly efficient manner as a viewing mechanism. Two flights of stairs lead to the highly complex cylindrical structure that sits on a round base 18 meters (59) in diameter and which is covered in Puuc-style friezes with projecting cornices.

Friezes at El Caracol (Wolfgang Sauber/CC BY-SA 3.0)

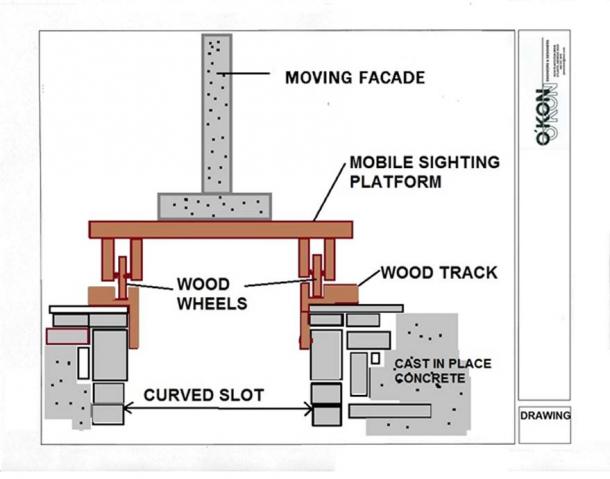

The tower, the main viewing area, stands 28 meters (92 feet) above ground level and is surrounded by two massive, curved slots. The west-facing slot drops down over eight meters (26 feet) into the base of the building, while the eastern-facing slot is only a few feet deep. We’ll return to these slots shortly, but it should be noted that each was designed to support a moveable viewing apparatus that anchored at the base.

Artist’s rendering of the movable façade provides an idea for how they were positioned within the massive slots. (Graphic by Mark Lamirande, of Lamirande Design

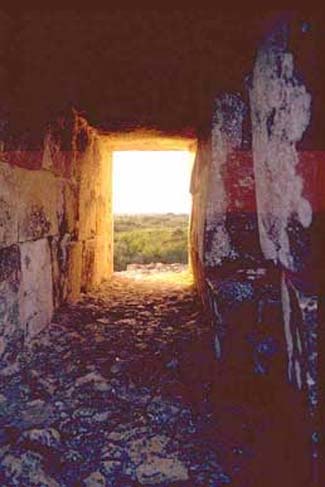

The construction of the Caracol tower contains a series of interesting technological and architectural innovations culminating in three concentric cylinders separated by ring vaulting. The outer cylinder has four doorways placed at the cardinal point of the compass. A circular “corridor” separates it from the middle cylinder which measures eight meters (26 feet) in diameter. The second circle has four doors in a quincunx (five points arranged in a cross) arrangement in relations to those on the exterior. Like the first, it has a vaulted ceiling and contains a solid central core of masonry in which a narrow spiral passage leads to the high chamber, with spyholes in the walls. The building was heavily damaged when it was discovered and only three surviving spyholes provide us enough information to understand the function of the observatory.

A spyhole at El Caracol. (Via author)

The Maya Astronomical System Revealed

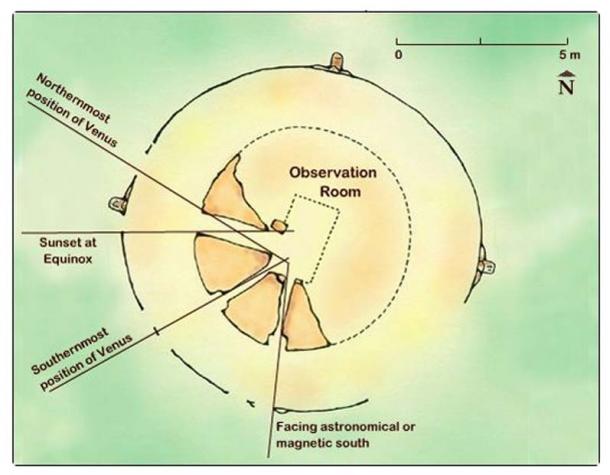

Astronomical observations were made by examining the angles traced by light traveling along the tunnel as formed by a long, narrow spyhole. Measurements of the angle between the right-hand edge of the external opening and the left-hand edge of the interior opening allow for extremely precise observations. What we now understand is that the first observation aperture faces directly south; the second aligns with the setting of the moon on March 21; the third faces directly towards the west and towards the point where the sun sets at the equinoxes on March 21 and September 21.

The spyholes were situated exactly where the sun was positioned for equinox and solstice observations. (Via author)

Finally, the second viewpoint through the same spyhole corresponds to the setting of the sun at the summer solstice on June 21. These details are the foundations of the Maya astronomical system; the X and Y upon which the more detailed observations are based.

Missing Pieces to the Puzzle

How, you might ask, were the Maya able to calculate the movements of Venus, and other planets including the sun and the moon? Archaeologists would have us believe that the naked eye was sufficient for these observations and calculations, but I think there is a missing piece to this puzzle. A good deal of the upper section of the observatory is damaged and must have contained addition spyholes and other tools for viewing the heavens.

Scientists have determined that the sun, moon and Venus were key factors in Maya astronomical observation and have determined that the spyholes were used to track the movement of the planets. (Source: YucatanToday.com)

The original design for the observatory appears to have been multi-functional and may have included a number of engineering features that allowed for enhanced viewing. Because the tower was heavily eroded, we’ll never know how the complete observatory looked when it was in operation, but there are a number of clues that until now have never been well understood. I wanted to get the opinion of an engineer to determine if what I suspected in the design of the terrace was possible. I called on Jim O’Kon, a forensic engineer, and expert on Maya construction techniques, to review my hypothesis and to comment on the function of the strange slots.

Mechanics and optics for enhanced viewing

Designed into the outer terrace are two slots (pits) that follow the curvature of the tower and support a viewing mechanism. The west-facing slot is approximately eight meters (26 feet) deep and could have housed an articulating façade which moved with the movement of the planets. The smaller eastern slot is about 2.5 meters (eight feet) deep and had limited range and motion. I’ve reasoned that the Maya built these slots to support a viewing apparatus or a movable façade and fixed optics. This outer structure could be moved up or down depending on the operator and was manually positioned at the bottom of each slot.

This aerial photo of the observatory shows the curved slots which supported an East/West facing articulating façade. (Screenshot from Fly Riviera Maya, Youtube.com)

Engineering rendering provided by Jim O’Kon. This track system sat at the base of each slot (pit) and supported an articulating façade. (Image: Jim O’Kon)

O’Kon is convinced the Maya developed the wheel, (evidenced by the numerous toys uncovered with wheels), and I believe in the distant past, the addition of mechanics or gears allowed the apparatus to move vertically and horizontally, like an elevator for observing the heavens. These new functions of the observatory would allow for day or evening observation.

This rare photo, taken at Copán, an ancient Maya city in Honduras, reveal the details of a gearing system, which early generations may have used in buildings and at the Observatory at Chichen Itza. (Photo from Astronaut Gods of the Maya, by Erich von Däniken).

A unique engineering feature suggested by O’Kon, is a track system which supported the movement of the façade, and conformed to the slots, interior siding, and flooring. The track and base with wheels housed the moving apparatus, and was manually operated within the interior of the terrace and accessed through a doorway designed into the western wall. We know the Romans used similar lift systems to rise and lower platforms at the massive Colosseum in Rome. These elevators were designed to move scenery, gladiators and even wild animals onto the main amphitheater for viewing entertainment. I believe the same type of elevator was used to operate the massive viewing façades within the observatory. The artist rendering shows an approximate position for the façades and how they may have appeared. What we cannot know is what additional devices or tools were embedded into each section to observe the heavens.

The western slot. Notice the reinforced walls. (Via author)

Lenses for Celestial Movements

To view celestial movements, the Maya would have needed the use of optics, (lens cut and polished and fitting into a device.) The earliest known lenses are found in former Assyria, (Iraq and Syria) and in Egypt, and date to around 750 BC. These early lenses were shaped from crystal and polished for optimum clarity. We don’t see modern lenses until the Middle Ages when the science of optics was conceived and early telescopes developed.

It’s strange to note that although no lenses have ever been discovered in Central America, some of the most sophisticated crystal carvings of human skulls have be uncovered. The most noted of these skulls are the Mitchel-Hedges, Aztec and Maya skulls, each cut, sanded and polished with an exacting level of precision found in modern craftsmanship. Until we find a lens we can only assume that the Maya had a form of magnifying the planets they studied.

The crystal skull at the British Museum, similar in dimensions to the more detailed Mitchell-Hedges skull. (Rafał Chałgasiewicz/CC BY 3.0)

El Caracol is unique among Maya observatories because its design is not duplicated anywhere else in the world, and, as previously noted, appears to have been a teaching tool for higher learning. Because of its great age, we’re left with many questions as to it operation, function and what the Maya may have discovered as they scanned the cosmos. We can only wait in anticipation for the next codices or sacred astronomy book(s) to reveal themselves as archaeologists continue to unearth the ancient history of the Maya.

Source: Ancient Origins

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.