The finding shows that oxygen can be generated in space without the need for life, and could influence how researchers search for signs of life on exoplanets.

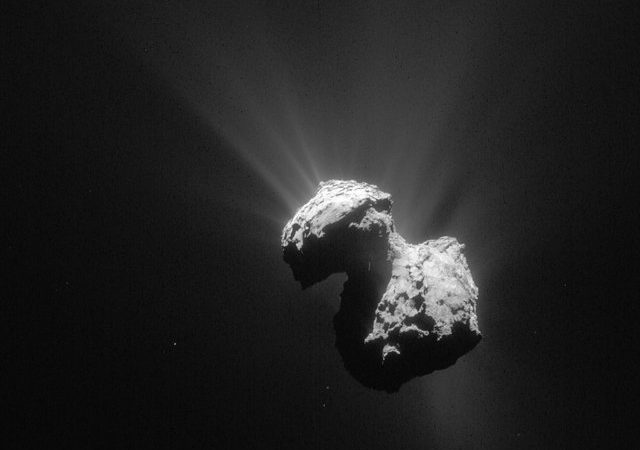

In 2015, scientists announced the detection molecular oxygen at Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, which was studied by the Rosetta spacecraft. It was the “biggest surprise of the mission,” they said — a discovery that could change our understanding of how the solar system formed.

While molecular oxygen is common on Earth, it is rarely seen elsewhere in the universe. In fact, astronomers have detected molecular oxygen outside the solar system only twice, and never before on a comet.

The initial explanation for the oxygen found in the faint envelope of gas that surrounds the comet was that the oxygen was frozen inside the comet since the beginning of our solar system some 4.6 billion years ago. It was believed that the oxygen had thawed as the comet made its way closer to the Sun.

But researchers are rethinking that theory, thanks to a chemical engineer from Caltech who usually works on developing microprocessors.

Konstantinos P. Giapis was intrigued by the Rosetta finding because it appeared to him that the chemical reactions occurring on Comet 67P’s surface were very similar to experiments he had been performing in his lab for the past 20 years. Giapis studies chemical reactions involving high-speed charged atoms, or ions, colliding with semiconductor surfaces in order to develop faster computer chips and larger digital memories for computers and phones.

“I started to take an interest in space and was looking for places where ions would be accelerated against surfaces,” Giapis said in a statement. “After looking at measurements made on Rosetta’s comet, particularly regarding the energies of the water molecules hitting the comet, it all clicked. What I’ve been studying for years is happening right here on this comet.”

In a new paper, Giapis and his co-author and Caltech colleague Yunxi Yaos propose that the molecular oxygen at Comet 67P is not ancient, but is being produced right now by interactions within the comet’s nebulous aura, or coma, between water molecules coursing off the comet and particles streaming from the sun.

“We have shown experimentally that it is possible to form molecular oxygen dynamically on the surface of materials similar to those found on the comet,” said Yaos.

Here’s how it works: Water vapor molecules stream off the comet as it is heated by the sun. The water molecules become ionized, or charged, by ultraviolet light from the sun, and then the sun’s wind blows the ionized water molecules back toward the comet. When the water molecules hit the comet’s surface, which contains oxygen bound in materials such as rust and sand, the molecules pick up another oxygen atom from the surface and O2 is formed.

“This abiotic production mechanism is consistent with reported trends in the 67P coma,” the researchers write in their paper, “and raises awareness of the role of energetic negative ions,” not only in comets but other planetary bodies as well.

This oxygen-producing mechanism could be happening in a wide range of situations.

“Understanding the origin of molecular oxygen in space is important for the evolution of the Universe and the origin of life on Earth,” the researchers wrote.

The finding muddies the waters in how detecting oxygen in the atmospheres of exoplanets might not necessarily point to life, as this abiotic process means that oxygen can be produced in space without the need for life. The researchers say this finding might influence how researchers search for signs of life on exoplanets in the future.

“We had no idea when we built our laboratory setups that they would end up applying to the astrophysics of comets,” said Giapis. “This original chemistry mechanism is based on the seldom-considered class of Eley-Rideal reactions, which occur when fast-moving molecules, water in this case, collide with surfaces and extract atoms residing there, forming new molecules. All necessary conditions for such reactions exist on comet 67P.”

Source: Seeker

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.