A new study pursues a kind of “paleontology” for gravitational waves in an attempt to explain how and why black holes collide and merge.

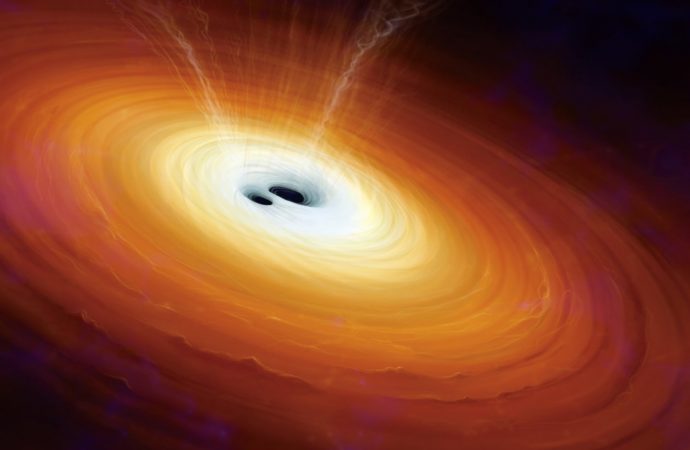

Last year, scientists announced that they had finally observed gravitational waves, the elusive and long sought-after ripples in the fabric of spacetime that were first posited by Albert Einstein. The waves came from a catastrophic event — the collision of two black holes located about 1.3 billion light years away from Earth — and the released energy undulated across the universe, much like ripples in a pond.

The detection by the upgraded Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (Advanced LIGO), along with two subsequent gravitational wave discoveries, confirmed a major prediction of Einstein’s 1915 general theory of relativity and heralded a new era in physics, allowing scientists to study the universe in a new way by using gravity instead of light.

But a fundamental question remains unanswered: How and why do black holes collide and merge?

In order for the black holes to merge, they must start out very close together by astronomical standards, no more than about a fifth of the distance between the Earth and the Sun. But only stars with very large masses can become black holes, and during the course of their lives, these stars expand to become even larger.

A new study published in Nature Communications uses a model called COMPAS (Compact Object Mergers: Population Astrophysics and Statistics) in an attempt to answer how large binary stars that would eventually become black holes fit within a very small orbit. COMPAS allows the researchers to pursue a kind of “paleontology” for gravitational waves.

“A paleontologist, who has never seen a living dinosaur, can figure out how the dinosaur looked and lived from its skeletal remains,” said Ilya Mandel from the University of Birmingham in the UK, the paper’s senior author, in a statement. “In a similar way, we can analyze the mergers of black holes, and use these observations to figure out how those stars interacted during their brief but intense lives.”

What they found was that even two widely separated “progenitor” stars can interact when they expand, engaging in several episodes of mass transfer.

The researchers started by analyzing the three gravitational wave events that were detected by LIGO and attempted to see if all three black hole collisions evolved in the same way, which they call “classical isolated binary evolution via a common-envelope phase.”

It starts with two massive progenitor stars at quite wide separations. As the stars expand, once they come so close that they cannot escape each other’s gravity, they begin to interact and engage in several episodes of mass transfer. This results in a very rapid, dynamically unstable event that envelops both stellar cores in a dense cloud of hydrogen gas.

“Ejecting this gas from the system takes energy away from the orbit,” the team said. “This brings the two stars sufficiently close together for gravitational-wave emission to be efficient, right at the time when they are small enough that such closeness will no longer put them into contact.”

It actually takes few million years to form two black holes, with a possible subsequent delay of billions of years before the black holes merge and form a single, larger black hole. But that merger event itself can be quick and violent.

The researchers said the simulations with COMPAS have also helped the team to understand the typical properties of the binary stars that can go on to form such pairs of merging black holes and the environments where this can happen.

For example, the team found that a merger of two black holes with significantly unequal masses would be a strong indication that the stars formed almost entirely from hydrogen and helium — called low-metallicity stars — with other elements contributing fewer than 0.1 percent of stellar matter (for comparison, this fraction is about 2 percent in our Sun). They were able to determine that all three events detected by LIGO could have formed in low-metallicity environments.

“The beauty of COMPAS is that it allows us to combine all of our observations and start piecing together the puzzle of how these black holes merge, sending these ripples in spacetime that we were able to observe at LIGO,” said Simon Stevenson, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Birmingham and the paper’s lead author.

The team will continue to use COMPAS to gain a greater understanding how the binary black holes discovered by LIGO could have formed, and how future observations could tell us even more about the most catastrophic events in the universe.

Source: Seeker

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.