The 2,000-year-old stone block was likely cut to be used in a temple, but was abandoned because it was unsuitable for transporting.

German archaeologists have discovered the largest stone ever carved by human hands, possibly dating to more than 2,000 years ago.

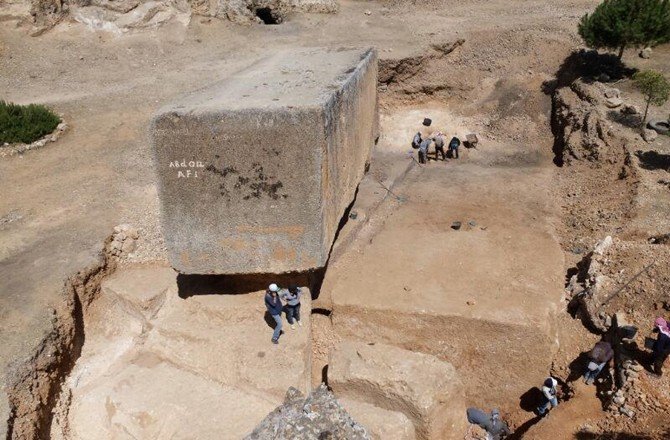

Still partially buried, the monolith measures 19.6 meters (64 feet) in length, 6 meters (19.6 feet) wide, and is at least 5.5 meters (18 feet) high. Its weight is estimated at a bulky 1,650 tons, making it biggest stone block from antiquity.

It was found by a team from the German Archaeological Institute in a stone quarry at Baalbek in Lebanon. Known as Heliopolis, “the city of the sun,” during the Roman rule, Baalbek housed one of the grandest sanctuaries in the empire.

The limestone quarry was located about a quarter of a mile from the temple complex and houses other two massive building blocks – one weighting about 1,240 tons, the other, known as the “Hajjar al-Hibla,” or The Stone of the Pregnant Woman, about 1000 tons.

Right next to the fully exposed Hajjar al-Hibla stone and underneath it, the archaeologists found a third block.

“The level of smoothness indicate the block was meant to be transported and used without being cut,” the German Archaeological Institute said in a statement.

“Thus this is the biggest boulder known from antiquity,” it added.

The team worked under the local supervision of Jeanine Abdul Massih, a long-term cooperation partner in the Baalbek project of the German Archaeological Institute’s Orient Department. The main purpose was to find new information about the mining techniques and the transportation of the megaliths.

Archaeologists believe the limestone blocks date back to at least 27 B.C., when Baalbek was a Roman colony and construction on three major and several minor temples began, lasting until the 2nd century A.D.

“Massive stone blocks of a 64-foot length were used for the podium of the huge Temple of Jupiter in the sanctuary,” the archaeologists said.

Only portions of the temple remain, including six massive columns and 27 gigantic limestone blocks at its base. Three of them, weighting about 1,000 tons each, are known as the “Trilithon.”

How these monoliths were transported and precisely positioned during the temple construction remains a mystery. Some even argue the block was laid by an unknown earlier culture predating even Alexander the Great, who founded Heliopolis in 334 B.C.

The newly uncovered stone block was likely cut to be used in the temple, but was probably abandoned because it was unsuitable for transporting.

Indeed, the Hajjar al-Hibla block nearby provided some clues: it was probably left in the quarry because the stone quality at one edge proved to be poor.

“It would have probably cracked during transportation,” the archaeologists said.

Further excavations will attempt to establish whether the bigger block suffered from the same problem.

Image: The largest stone block, partially buried. To the left is the Hajjar al-Hibla stone. Credit: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut.

Archaeologists in Abydos, Egypt have discovered the tomb and remains of Woseribre Senebkay, a previously unknown pharaoh who reigned more than 3,600 years ago.

Dating to about 1650 B.C. during Egypt’s Second Intermediate Period, Senebkay’s tomb lay close to a larger royal sarcophagus chamber, recently identified as belonging to a king Sobekhotep (probably Sobekhotep I, ca. 1780 B.C.) of the 13th Dynasty.

Badly plundered by ancient tomb robbers, the tomb of Senebkay is modest in scale. It consists of four chambers with a decorated limestone burial chamber. viously unknown pharaoh who reigned more than 3,600 years ago.

A painted scene in the burial chamber shows the goddesses Neith and Nut, protecting Senebkay’s shrine.

The skeleton of Woseribre Senebkay, who appears to be one of the earliest kings of a forgotten Abydos Dynasty (1650–1600 B.C.) was found in a four chamber tomb amidst debris of his fragmentary coffin, funerary mask and canopic chest.

Although robbers ripped apart Senebkay’s mummy, Wegner’s team was able to recover and reassemble the pharaoh’s skeleton. Preliminary examination indicates he was about 1.75 m (5’10) tall, and died in his mid to late 40s.

Source: Seeker

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.