It’s possible that Mars had rings at one point and may have them again someday.

That’s the theory put forth by Purdue University scientists have developed a model that suggests that debris that was pushed into space from an asteroid or other body slamming into Mars around 4.3 billion years ago and alternates between becoming a planetary ring and clumping up to form a moon.

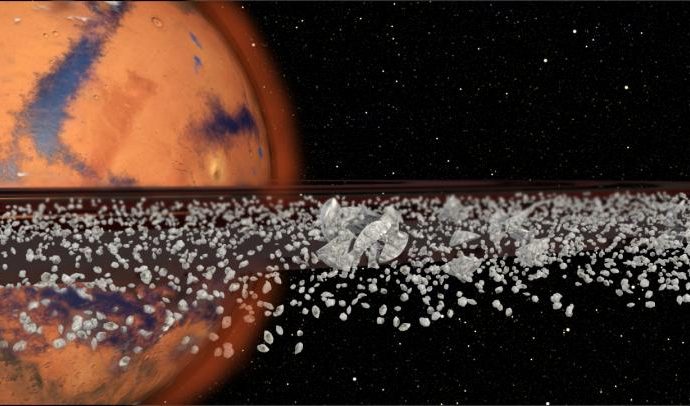

A theory exists that Mars’ large North Polar Basin or Borealis Basin, which covers about 40 percent of the planet in its northern hemisphere, was created by that impact, sending debris into space.”That large impact would have blasted enough material off the surface of Mars to form a ring,” said Andrew Hesselbrock. Hesselbrock and Minton’s model suggests that as the ring formed and the debris slowly moved away from the planet and spread out, it began to clump and eventually formed a moon. Over time, Mars’ gravitational pull would have pulled that moon toward the planet until it reached the Roche limit, the distance within which the planet’s tidal forces will break apart a celestial body that is held together only by gravity.

Phobos, one of Mars’ moons shown above, is getting closer to the planet. According to the model, Phobos will break apart upon reaching the Roche limit and become a set of rings in roughly 70 million years. Depending on where the Roche limit is, Minton and Hesselbrock believe this cycle may have repeated between three and seven times over billions of years. Each time a moon broke apart and reformed from the resulting ring, its successor moon would be five times smaller than the last, according to the model, and debris would have rained down on the planet, possibly explaining enigmatic sedimentary deposits found near Mars’ equator.

“Phobos has really low density,” said James Head, Brown University professor of geological sciences. “Is that low density due to ice in its interior or is it due to Phobos being completely fragmented, like a loose rubble pile? We don’t know.”

Phobos contains tons of dust, soil, and rock blown off the Martian surface by large projectile impacts. Phobos’ orbital path plows through occasional plumes of Martian debris, meaning the tiny moon has been gathering Martian castoffs for millions of years.

Scientists are still not sure where it came from. Is it a chunk of Mars that was knocked off by an impact early in Martian history, or is it an asteroid snared in Mars’s orbit? There are also questions about whether its interior might hold significant amounts of water. The 27km-wide moon, which many scientists suspect may actually be a captured asteroid.

In a recent development, scientists say they have uncovered firm evidence that Phobos, is made from rocks blasted off the Martian surface in a catastrophic event, solving a long-standing puzzle. It has been suggested that both Phobos and Deimos could be asteroids that formed in the main asteroid belt and were then “captured” by Mars’s gravity.

“You could have had kilometer-thick piles of moon sediment raining down on Mars in the early parts of the planet’s history, and there are enigmatic sedimentary deposits on Mars with no explanation as to how they got there,” said David Minton, assistant professor of Earth, atmospheric and planetary sciences. “And now it’s possible to study that material.”

Other theories suggest that the impact with Mars that created the North Polar Basin led to the formation of Phobos 4.3 billion years ago, but Minton said it’s unlikely the moon could have lasted all that time. Also, Phobos would have had to form far from Mars and would have had to cross through the resonance of Deimos, the outer of Mars’ two moons. Resonance occurs when two moons exert gravitational influence on each other in a repeated periodic basis, as major moons of Jupiter do. By passing through its resonance, Phobos would have altered Deimos’ orbit. But Deimos’ orbit is within one degree of Mars’ equator, suggesting it has had no effect on Phobos.

“Not much has happened to Deimos’ orbit since it formed,” Minton said. “Phobos passing through these resonances would have changed that.”

Richard Zurek of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, is the project scientist for NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, whose gravity mapping provided support for the hypothesis that the northern lowlands were formed by a massive impact.

“This research highlights even more ways that major impacts can affect a planetary body,” he said.

Minton and Hesselbrock will now focus their work on either the dynamics of the first set of rings that formed or the materials that have rained down on Mars from disintegration of moons.

Source: The Daily Galaxy

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.