Malta’s picturesque capital has been used as the set of Gladiator, Troy and King’s Landing in Game of Thrones – but it is also riven by subterranean passages that go back to the legendary Knights of Malta. As the city prepares to be European Capital of Culture, should the tunnels be opened to the public?

When Albert Dimech recognised us, rather than introducing himself, he simply said: “Follow me.”

Dimech had asked the artist Leanne Wijnsma and me to meet him in the centre of Valletta, Malta’s capital city and the European capital for culture in 2018. Wijnsma had been commissioned by the Valletta 2018 foundation to create a piece of artwork about the city’s subterranean world, and Dimech was our point of contact.

We arrived a few minutes late and out of breath, veering past tourists eating ice cream in the sun and taking photos of the dense vertical houses. Dimech immediately marched us toward the Malta Law Courts, where, to the dismay of the guards, he picked up a phone from behind the security desk and had an energetic conversation in Maltese that somehow secured access to the building.

He took us to the bin room where he kicked aside trash bags and cardboard boxes to reveal a tight, spiral staircase. “They only discovered this tunnel a few years ago,” he said as he descended. Where the torchlight bounced off the walls, we could see the indent of hundreds of thousands of rock pick swings, conjuring ghostly images of labourers excavating during the second world war – frantically carving out shelter for a populace reeling from the fierce aerial bombings by Mussolini and later, Hitler.

At the bottom of the staircase, we found ourselves standing in a foot of water. “There used to be a drainage system here – see the channels along the sides?” he said. “But it doesn’t drain so well any more. Your shoes are ruined.” Indeed, they were.

Punched out of the tunnel walls, in a zigzag pattern meant to diffuse shock waves, were dozens of shelters. Each was just large enough for a family of four to huddle in. The shelters were strung with electric lighting, and though they’re more than 70 years old, many of the lightbulbs were still intact.

Some of the shelters had altars carved into the walls, filled with personal effects: bowls, candles, wine bottles. I brushed away the stagnant water to reveal richly coloured floor tiles, and wondered why people would spend this much effort on the interior design of an emergency bunker.

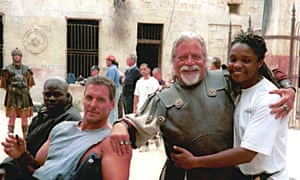

The answer to that is closely connected to the story of Valleta itself. A bountiful rock strategically located at the crossroads between Europe, North Africa and the Middle East, this most formidable of fortress cities is a Unesco world heritage site – as well as the set of Gladiator, Troy and the King’s Landing in Game of Thrones. But it is also riven by so many subterranean passageways, it’s a wonder it doesn’t slump into the Mediterranean. The entire city is a latent bunker.

Dimech is one of the many people in Valletta who have become obsessed by this underground heritage. Following him around an immense circular brick structural support and down more stairs, we pulled through a curtain of arm-thick ficus roots, stretching down from street level to drink at subterranean pools.

On the other side of the roots was a 12 metre-high chamber, illuminated by a beam of light from the grill of a manhole cover above, where we could hear conversations and the screeching sounds of terrace chairs scooting across paving stones. Before us was a rubbish-strewn underground beach, like something out of a JG Ballard novel, speckled with hundreds of red cookie wrappers. The scale of the space was crushing.

Dimech grew impatient. “This is nothing. Come see the other side.” As we edged around a dividing wall, there was a collective inhale. Directly beneath Great Siege Square, with its swarms of tourists, was a 16th-century public cistern constructed by the Knights of Malta.

The Knights of Malta, also known as the Order of St John, formed in 1048, making them one of the oldest Catholic religious orders in the world. The knights arrived here in 1530, at the bequest of Holy Roman emperor Charles V, who sought to extend Catholic control over the Mediterranean by seizing Malta. The Ottoman empire, unfortunately, had the same idea. In 1565, Suleiman the Magnificent moved to take the island, and war erupted.

Many of the fierce battles between the Knights and the Turks during what became known as the Great Siege of Malta raged underground. The limestone here is soft but dense, making it ideal for carving fortifications – but also for tunnelling under them. Historian Ernle Bradford captures the drama in his book The Great Siege: Malta 1565, where he describes how Turkish sappers and Maltese counter miners, digging for their lives, often broke through into the enemy galleries, where “before either side could withdraw to fire their charges, Christian and Moslem came to grips with pick, shovel, and dagger”.

The Knights held the line, though. After the wars died down, Valletta was named Malta’s new capital, and the city as we know it was founded. It had a natural defensive advantage: the Mount Sciberras Peninsula overlooks what would become the Grand Harbour, and guards the deepest natural harbour in the Mediterranean.

Underneath the city, in the malleable limestone, the Knights etched a gridded sewer system, and carved out caches for food and water, safe behind the city walls. The Maltese government today claims Valletta is “Europe’s first planned city”.

It is also a rapidly changing one. As Malta urbanises and rents rise drastically, many citizens are being pushed to the suburbs, even though the bulk of the jobs here are in foreign trade, manufacturing and tourism. The mayor, Alexiei Dingli, has said rents started to skyrocket “when the government began a number of high profile regeneration projects in the capital”.

He also pointed the finger at the capital of culture designation. This scheme, which has run since 1985, injects cash into cities for a series of cultural events – music, dance, exhibitions, lectures and more – and to improve infrastructure. It can be a great opportunity for a city, but it can also lead to local tensions about over expectations, legacy and gentrification.

Valletta has been no exception. Controversy recently swirled around the redesign of the city gate by architect Renzo Piano, who proposed a modernist structure that, some argued, is not in keeping with Malta’s more baroque aesthetics. Architectural Review claimed that the Maltese government failed to notify Unesco about the plan, calling into doubt the city’s continued presence on the world heritage list – though these concerns have reportedly since been resolved. Dimech has plans of his own to open the cistern to tourists, a project that is likely to generate some debate.

Over the past decade, various urban regeneration schemes have also disturbed the dormant Valletta underworld. In 2009, the city conducted an archaeological survey under St George’s Square, next to the presidential palace, in order to build an underground car park – and found a lost tunnel. National Geographic reported at the time that “the tunnel’s connecting branches may have included service passages used by the Knights’ chief hydraulic engineer, or fontaniere”.

Claude Borg was the architect in charge of the car park project, which was scrapped after the discovery. In his offices in Floriana, Borg told Wijnsma and me how he removed a jumble of heavy limestone blocks in the basement of an Italian restaurant on Archbishop Street and found a passageway to Valletta’s first freshwater fountain. There are rumours, he said, that the Knights built escape tunnels from the palace. “I can also tell you that this tunnel connects to the palace. If there was a secret escape route, this was it.”

Wijnsma – like me, Dimech and many Maltese people – is infatuated with urban underworlds, and has dedicated much time to digging them herself, often without permission. The problem with her self-dug tunnels, however, is that “they are always temporary and not very accessible”.

For her new project in Valletta, therefore, Wijnsma decided to do a 3D scan of the cistern, so that visitors can explore the tunnels without having to climb into them. Inside the tunnel, she also proposes making a digital connection to Leeuwarden, the other 2018 European capital of culture, turning the cistern into a virtual wormhole between the two cities.

Borg was the first to step foot into the cistern since the second world war. Repaving works on Republic Street had broken through Great Siege Square, and he was called in to assess the damage. He descended with a colleague, who grabbed hold of a ficus root hanging from the ceiling – and brought down a large block on her head. “If she didn’t have a hard hat on, she would most certainly have died.”

When we told Borg about Dimech’s plan to open the tunnel to the public, he suggested there were better locations for such a project, which were not hard to find. This is because there is a direct relationship in Valletta between the underground and the surface: many urban open spaces exist precisely because the void underneath makes it challenging to build above them.

To locate cavernous underground spaces, tunnel hunters often pore over aerial images looking for open spaces like parks and squares. An observant visitor to Valletta will notice, for example, that several open expanses between buildings are covered in what resemble giant stone mushrooms. These plugs once sealed grain in underground silos, safe inside the city’s defences and ready for a siege. Records say that 12 cisterns, similar to the Great Siege cistern, stored fresh water for the city, and could quench the thirst of 40,000 people for four months. Most of these cisterns are located under public squares.

Valletta also once had an underground railway (1883-1931), which served as an air-raid shelter for 5,000 citizens during the second world war. Today, a linear park runs atop the railway, which tunnel anoraks will tell you is no coincidence: as above, so below. Like Argia from Calvino’s Invisible Cities, the city reflects itself in negative.

Of course, like any densely layered city, subterranean stories get multiplied in myth as well as memory. Local lore, bolstered by captivating historic records, suggest, for instance, that there was an under sea tunnel linking military outposts across the Grand Harbour. Others tell of the Knights of Malta riding through the underground in horse-drawn chariots.

In a bustling cafe near the palace, Zimmerman assured us both narratives were unlikely, and said he was “at a loss as to why people feel a need to embellish, since the reality of the Valletta underground is already so fascinating”. To prove his point he had us shimmy across a tiny ledge above the churning Mediterranean into a cavernous space carved underneath the city walls. “This was meant to be a second world war submarine base. The British started digging it and realised after some effort that the cost of construction would be about the same as building a new submarine. So here it is; why not preserve this incredible piece of history?”

Everywhere we went in the city, someone wanted to show us a warren, store or passageway. We were told of cellars, stables, crypts, granaries, bunkers, oil and ice pits, reservoirs, cisterns, sewers, sally ports and transport tunnels. In the densest neighbourhoods, it was unclear whether you were underground, above ground, or on the original surface of what was once Mount Sceberras.

Marc Zimmerman, of the group Malta Underground, took us down a coastal path to see an outfall of the Valletta sewage system. As we wiggled into it, he explained that it was constructed long before London had begun to consider major sanitation works. In fact, much of Valletta’s subterranean tangle is denser, older and more complicated than London’s.

Wijnsma spoke with 83-year-old John Sciberras, who helped dig a bunker for his 18-person family when he was only seven years old. The British had occupied the island to defend against Rommel, who believed Malta was the key to retaining control of North Africa for the Nazis. “Everybody was digging, digging digging,” said Sciberras. “So we had a big shelter. One corridor, one central room, one small room on the left and on the right. My father made me a little chipper. We kept on going, ‘chik, chik, chik,’ all day and night. Everybody was in a hurry to dig.”

Sylvana Meli, 57, told Wijnsma that her family “survived war only because of our underground shelters. Coming out alive was a rebirth. That makes us all children of the underground. Everyone who doesn’t know about what lies right beneath our feet here in Valletta should know that.”

***

A few weeks after our first dizzying trip, we returned to the Great Siege Square cistern to a dismaying sight: fluorescent orange surveyor paint was sprayed on every surface. Such paint, the architect Edward Said told us later, likely “can’t be removed without damaging the architecture in some way”.

Said was apprehensive: the cistern space was unique in Malta for the way it tied together layers across the history of the city, and he did not want to see it marred during efforts to open it to the public. The tunnel, he said, didn’t only connect to people’s basements, but to the national library, to St John’s Co-Cathedral and perhaps even to the presidential palace. It was a primary artery, and needed to be treated with care.

The Malta railway tunnel may also soon become a sticking point. The railway, which connects Floriana to Valletta and is currently used as a telecommunication cable corridor, also branches into numerous second world war shelters filled with artefacts. Every year, the local council runs tours of the subway, and every year these tours are packed – yet at least one local writer argues that it would serve a better function as a transport corridor than a cable run and tourist attraction.

Although almost everyone we met was very enthusiastic about Valletta becoming the European capital of culture, many expressed concerns that the pressure of the cultural event might, ironically, cannibalise the city’s heritage for the benefit of a temporary celebration.

Staring at the 450-year-old limestone blocks marked in lurid paint, Wijnsma said: “I’m worried the artwork will be the only reminder of what this place felt like,” given much more was needed to make the tunnel safe for visitors. “This is a classic heritage conundrum: in ‘cleaning up’ historic sites for tourism, they are often also exorcised of the very essences that make them rare.”

For all its ornamentation, monuments and street grid, Valletta is also in many ways the antithesis of a planned city. Each carefully stacked stone and strategically patinated statue is undermined, quite literally, by shooting galleries, blown-out bunkers and hidden strata – a dark heritage of waste, water, food storage and shelter systems built by military minds that left nothing to chance.

The city’s symphonic cultural complexity makes Valletta an ideal European capital of culture – but the conversations that will unfold over the celebrations will no doubt reveal some of the hazards of placing the local on a global plinth. And as usual, much of the drama will unfold in Valletta’s underworld.

Source: The Guardian

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.