Curiosity rover findings add to a puzzle about ancient Mars because the same rocks that indicate a lake was present also indicate there was very little carbon dioxide in the air to help keep a lake unfrozen.

Mars scientists are wrestling with a problem. Ample evidence says ancient Mars was sometimes wet, with water flowing and pooling on the planet’s surface. Yet, the ancient sun was about one-third less warm and climate modelers struggle to produce scenarios that get the surface of Mars warm enough for keeping water unfrozen.

A leading theory is to have a thicker carbon-dioxide atmosphere forming a greenhouse-gas blanket, helping to warm the surface of ancient Mars. However, according to a new analysis of data from NASA’s Mars rover Curiosity, Mars had far too little carbon dioxide about 3.5 billion years ago to provide enough greenhouse-effect warming to thaw water ice.

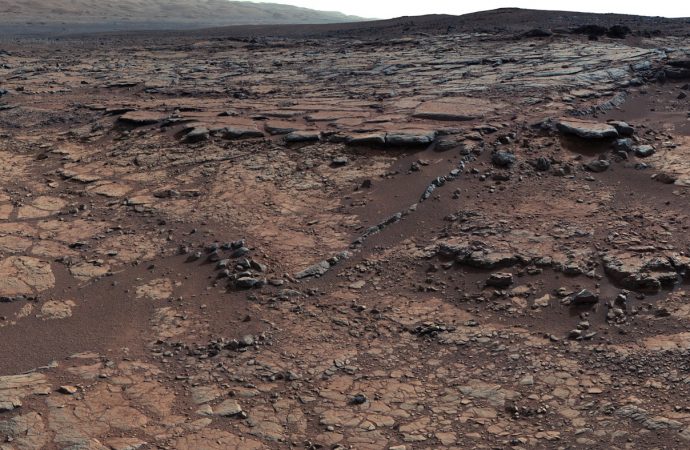

The same Martian bedrock in which Curiosity found sediments from an ancient lake where microbes could have thrived is the source of the evidence adding to the quandary about how such a lake could have existed. Curiosity detected no carbonate minerals in the samples of the bedrock it analyzed. The new analysis concludes that the dearth of carbonates in that bedrock means Mars’ atmosphere when the lake existed — about 3.5 billion years ago — could not have held much carbon dioxide.

“We’ve been particularly struck with the absence of carbonate minerals in sedimentary rock the rover has examined,” said Thomas Bristow of NASA’s Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California. “It would be really hard to get liquid water even if there were a hundred times more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere than what the mineral evidence in the rock tells us.” Bristow is the principal investigator for the Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) instrument on Curiosity and lead author of the study being published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Curiosity has made no definitive detection of carbonates in any lakebed rocks sampled since it landed in Gale Crater in 2012. CheMin can identify carbonate if it makes up just a few percent of the rock. The new analysis by Bristow and 13 co-authors calculates the maximum amount of carbon dioxide that could have been present, consistent with that dearth of carbonate.

In water, carbon dioxide combines with positively charged ions such as magnesium and ferrous iron to form carbonate minerals. Other minerals in the same rocks indicate those ions were readily available. The other minerals, such as magnetite and clay minerals, also provide evidence that subsequent conditions never became so acidic that carbonates would have dissolved away, as they can in acidic groundwater.

The dilemma has been building for years: Evidence about factors that affect surface temperatures — mainly the energy received from the young sun and the blanketing provided by the planet’s atmosphere — adds up to a mismatch with widespread evidence for river networks and lakes on ancient Mars. Clues such as isotope ratios in today’s Martian atmosphere indicate the planet once held a much denser atmosphere than it does now. Yet theoretical models of the ancient Martian climate struggle to produce conditions that would allow liquid water on the Martian surface for many millions of years. One successful model proposes a thick carbon-dioxide atmosphere that also contains molecular hydrogen. How such an atmosphere would be generated and sustained, however, is controversial.

The new study pins the puzzle to a particular place and time, with an on-the-ground check for carbonates in exactly the same sediments that hold the record of a lake about a billion years after the planet formed.

For the past two decades, researchers have used spectrometers on Mars orbiters to search for carbonate that could have resulted from an early era of more abundant carbon dioxide. They have found far less than anticipated.

“It’s been a mystery why there hasn’t been much carbonate seen from orbit,” Bristow said. “You could get out of the quandary by saying the carbonates may still be there, but we just can’t see them from orbit because they’re covered by dust, or buried, or we’re not looking in the right place. The Curiosity results bring the paradox to a focus. This is the first time we’ve checked for carbonates on the ground in a rock we know formed from sediments deposited under water.”

The new analysis concludes that no more than a few tens of millibars of carbon dioxide could have been present when the lake existed, or it would have produced enough carbonate for Curiosity’s CheMin to detect it. A millibar is one one-thousandth of sea-level air pressure on Earth. The current atmosphere of Mars is less than 10 millibars and about 95 percent carbon dioxide.

“This analysis fits with many theoretical studies that the surface of Mars, even that long ago, was not warm enough for water to be liquid,” said Robert Haberle, a Mars-climate scientist at NASA Ames and a co-author of the paper. “It’s really a puzzle to me.”

Researchers are evaluating multiple ideas for how to reconcile the dilemma.

“Some think perhaps the lake wasn’t an open body of liquid water. Maybe it was liquid covered with ice,” Haberle said. “You could still get some sediments through to accumulate in the lakebed if the ice weren’t too thick.”

A drawback to that explanation is that the rover team has sought and not found in Gale Crater evidence that would be expected from ice-covered lakes, such as large and deep cracks called ice wedges, or “dropstones,” which become embedded in soft lakebed sediments when they penetrate thinning ice.

If the lakes were not frozen, the puzzle is made more challenging by the new analysis of what the lack of a carbonate detection by Curiosity implies about the ancient Martian atmosphere.

“Curiosity’s traverse through streambeds, deltas, and hundreds of vertical feet of mud deposited in ancient lakes calls out for a vigorous hydrological system supplying the water and sediment to create the rocks we’re finding,” said Curiosity Project Scientist Ashwin Vasavada of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California. “Carbon dioxide, mixed with other gases like hydrogen, has been the leading candidate for the warming influence needed for such a system. This surprising result would seem to take it out of the running.”

When two lines of scientific evidence appear irreconcilable, the scene may be set for an advance in understanding why they are not. The Curiosity mission is continuing to investigate ancient environmental conditions on Mars. It is managed by JPL, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington. Curiosity and other Mars science missions are a key part of NASA’s Journey to Mars, building on decades of robotic exploration to send humans to the Red Planet in the 2030s.

Source: JPL NASA

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.