Astronomers in the US are setting up an experiment which, if it fails – as others have – could mark the end of a 30-year-old theory

Deep underground, in a defunct gold mine in South Dakota, scientists are assembling an array of odd devices: a chamber for holding tonnes of xenon gas; hundreds of light detectors, each capable of pinpointing a single photon; and a vast tank that will be filled with hundreds of gallons of ultra-pure water. The project, the LZ experiment, has a straightforward aim: it is designed to detect particles of an invisible form of matter – called dark matter – as they drift through space.

It is thought there is five times more dark matter than normal matter in the universe, although it has yet to be detected directly. Finding it would solve one of science’s most baffling mysteries and explain why galaxies are not ripped apart by stars flying off into deep space.

However, many scientists believe time is running out for the hunt, which has lasted 30 years, cost millions of pounds and produced no positive results. The LZ project – which is halfway through construction – should be science’s last throw of the dice, they say. “This generation of detectors should be the last,” said astronomer Stacy McGaugh at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. “If we don’t find anything we should accept we are stuck and need to find a different explanation, perhaps by modifying our theories of gravity, to explain the phenomena we attribute to dark matter.”

Other researchers reject this view: “Theory indicates we have a really good chance of finding dark matter particles,” said Chamkaur Ghag, chair of the Dark Matter UK consortium. “This is certainly not the time to talk of giving up.”

The concept of dark matter stems from observations made in the 1970s. Astronomers expected to find that stars rotated more slowly around a galaxy the more distant they were from the galaxy’s centre, just as distant planets revolve slowly round the Sun. (Outermost Neptune moves round the Sun at a stately 12,000mph; innermost Mercury does so at 107,082mph.)

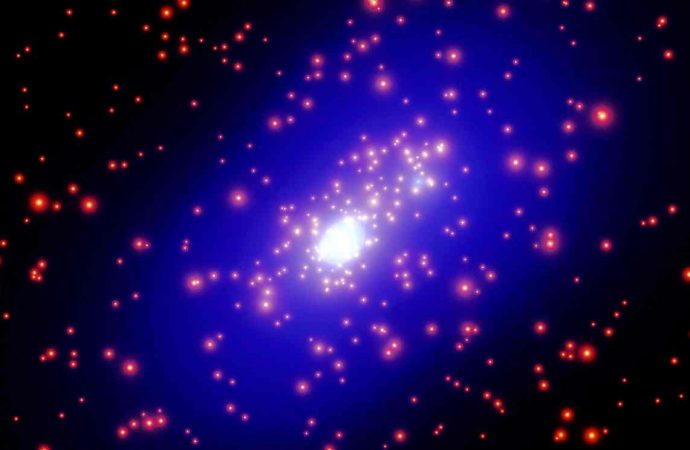

That prediction was spectacularly undone by observations, however. Stars at a galaxy’s edge orbit almost as fast as those near its centre. According to theory, they should be hurled into space. So astronomers proposed that invisible dark matter must be providing the extra gravity needed to hold galaxies together. Proposed sources of dark matter include burnt-out stars; clouds of dust and gas; and subatomic particles called Wimps – weakly interacting massive particles. All have since been discounted, except Wimps. Many astronomers are now convinced they permeate space and form halos round galaxies to give them the gravitational “muscle” needed to hold fast-flying stars in place.

Getting close to Wimps has not been easy. Scientists have built increasingly sensitive detectors deeper and deeper underground to protect them from subatomic particles that bombard Earth’s surface and which would trigger spurious signals. These devices resemble huge Russian dolls: a vast metal tank containing water – to provide added protection against incoming stray particles – is erected and, within this, a giant sphere of an inert gas such as xenon is suspended. Wimps making it through to the final tank should occasionally strike a xenon nucleus, producing a flash of light that can be pinpointed by electronic detectors.

Despite three decades of effort, this approach has had no success, a failure that is starting to worry some researchers. “We are now building detectors containing more and more xenon and which are a million times more sensitive than those we used to hunt Wimps 30 years ago,” said astrophysicist Professor David Merritt, of the Rochester Institute of Technology, New York. “And still we have found nothing.”

Last July, scientists reported that after running their Large Underground Xenon (Lux) experiment for 20 months they had still failed to spot a Wimp. Now an upgraded version of Lux is being built – the LZ detector, a US-UK collaboration – while other devices in Canada and Italy are set to run searches.

The problem facing Wimp hunters is that as their detectors get ever more sensitive, they will start picking up signals from other weakly interacting particles called neutrinos. Tiny, almost massless, these constantly whizz through our planet and our bodies. Neutrinos are not nearly heavy enough to account for the gravitational abnormalities associated with dark matter but are still likely to play havoc with the next generation of Wimp detectors.

“I believe the Wimp hypothesis will be truly dead when we reach that point,” said McGaugh. “It already has serious problems but if we get to the point where we are picking up all this background interaction, the game is up. You will not be able to spot a thing.”

This point is rejected by Ghag. “Yes, occasionally a neutrino will kick a xenon nucleus and produce a result that resembles a Wimp interaction. We will, initially, be in trouble. But as we characterise the collisions we should find ways to differentiate them and concentrate only on those produced by Wimps.”

But there is no guarantee that Wimps – if they exist – will ever interact with atoms of normal matter. “You can imagine a scenario where dark matter particles turn out to be so incredibly weak at interacting with normal matter that our detectors will never see anything,” said cosmologist Andrew Pontzen, of University College London.

Indeed, it could transpire that a Wimp is completely incapable of interacting with normal matter. “You would then be saying we can only make sense of the universe by proposing a hypothetical particle that we can never detect,” said Pontzen. “Philosophically that is a highly unsatisfactory situation. You would be saying you cannot prove or disprove a key hypothesis that underpins scientific understanding.”

However, Pontzen also pointed out that dark matter has proved invaluable in making scientific predictions and should not be dismissed too quickly. “Scientists in the late 20th century attempted to predict what the cosmic background radiation left behind by the Big Bang 13 billion years ago might look like. Those who used dark matter in their calculations were found to have got things spectacularly right when we later flew probes to study that radiation background. It shows there was dark matter right at the birth of the universe.”

McGaugh is unconvinced. He points to the failure of Geneva’s Large Hadron Collider, used to find the Higgs boson, to produce particles that might hint at the existence of Wimps. “It was hailed as the golden test but it has produced nothing, just like the other experiments.” Instead, more effort should be directed to developing new theoretical approaches to understanding gravity, he argues. One such theory is known as modified Newtonian dynamics, or Mond. It suggests that variations in the behaviour of gravity could account for the unexpected star speeds. Such approaches should take precedence if LZ should fail to find dark matter in the next two or three years, McGaugh said.

Ghag disagrees. “I think it is ridiculous to suggest we stop,” he said. “Are we just going to say ‘OK, we have no idea what makes up 85% of the universe just because we are finding it all a bit hard’? That’s not realistic.”

The uncertain nature of the problem was summed up by Pontzen. “We have been looking for dark matter for so long. Sometimes I think I should get real and admit something is up. On the other hand, the technology is getting better and we are opening up new possibilities of where to find dark matter. Which of these scenarios I feel closest to depends what sort of day I am having.”

Source: The Guardian

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.