Astronomers used the odd behaviour of a star to locate a black hole ‘hiding’ in the Large Magellanic Cloud.

Source: The Weather Network

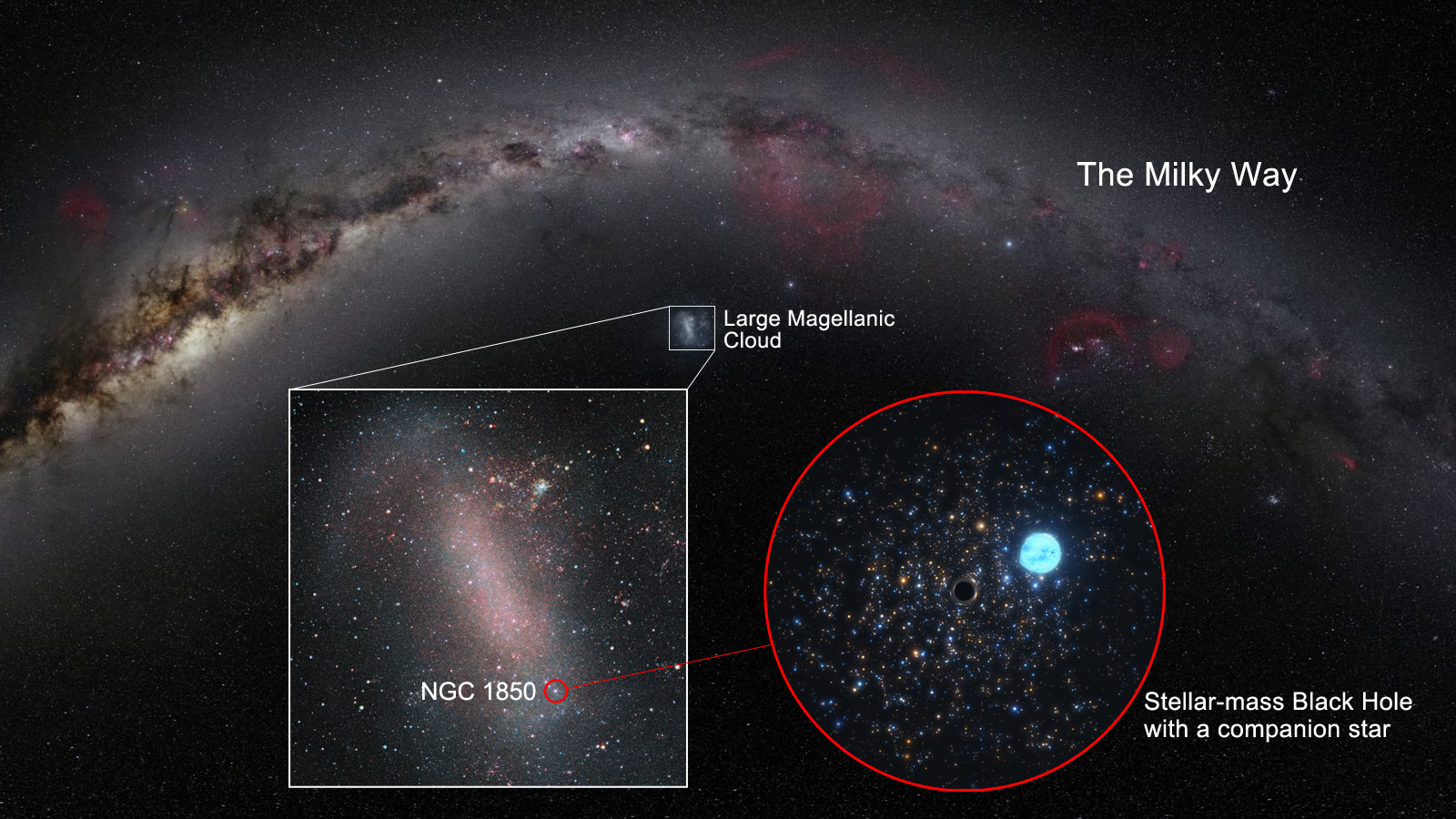

In the first discovery of its kind, astronomers found a stellar-mass black hole lurking in the Large Magellanic Cloud — its presence betrayed by the odd behaviour of its companion star. Moreover, the method of finding this lurker may reveal even more black holes, in both the Milky Way and beyond.

Black holes are notoriously difficult to find. They exist as tiny points in space where massive dying stars have literally collapsed in upon themselves, and their gravity is so strong that not even light can escape their grasp. As a result, they blend in with the blackness of space around them, and many of them go undetected by our telescopes.

The black holes that astronomers have located were discovered by looking for other things that reveal their presence. One way is by searching for intense sources of x-rays out in space. This is because black holes with close companion stars often pull matter off their partner, which emits x-rays as it is consumed by the black hole. Another is by watching for gravitational waves passing by Earth, originating from pairs of black holes (or black hole/neutron star pairs) merging in colossal collisions. A third method is by watching the behaviour of stars to see if some unseen source is causing them to behave strangely or move in unexpected ways.

The first two methods can find black holes at pretty much any distance, even across the universe. Until now, though, the third has only been used to locate black holes in our own galaxy. Perhaps the most famous is Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole that resides at the centre of the Milky Way.

Now, for the first time, astronomers have used the strange behaviour of a star outside our galaxy to discover its unseen stellar-mass black hole companion.

“Similar to Sherlock Holmes tracking down a criminal gang from their missteps, we are looking at every single star in this cluster with a magnifying glass in one hand trying to find some evidence for the presence of black holes but without seeing them directly,” Dr. Sara Saracino from the Astrophysics Research Institute of Liverpool John Moores University said in a press release from the European Southern Observatory.

“The result shown here represents just one of the ‘wanted criminals’, but when you have found one, you are well on your way to discovering many others, in different clusters,” Saracino added.

The search for this ‘hidden’ black hole involved over two years of observations of NGC 1850, an immense cluster of thousands of stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud, one of the satellite galaxies of our Milky Way. At only around 100 million years old, NGC 1850 is very young by cosmic standards. Saracino and her team focused on NGC 1850 using the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) instrument at the ESO’s Very Large Telescope, located high in the Atacama Desert in northern Chile.

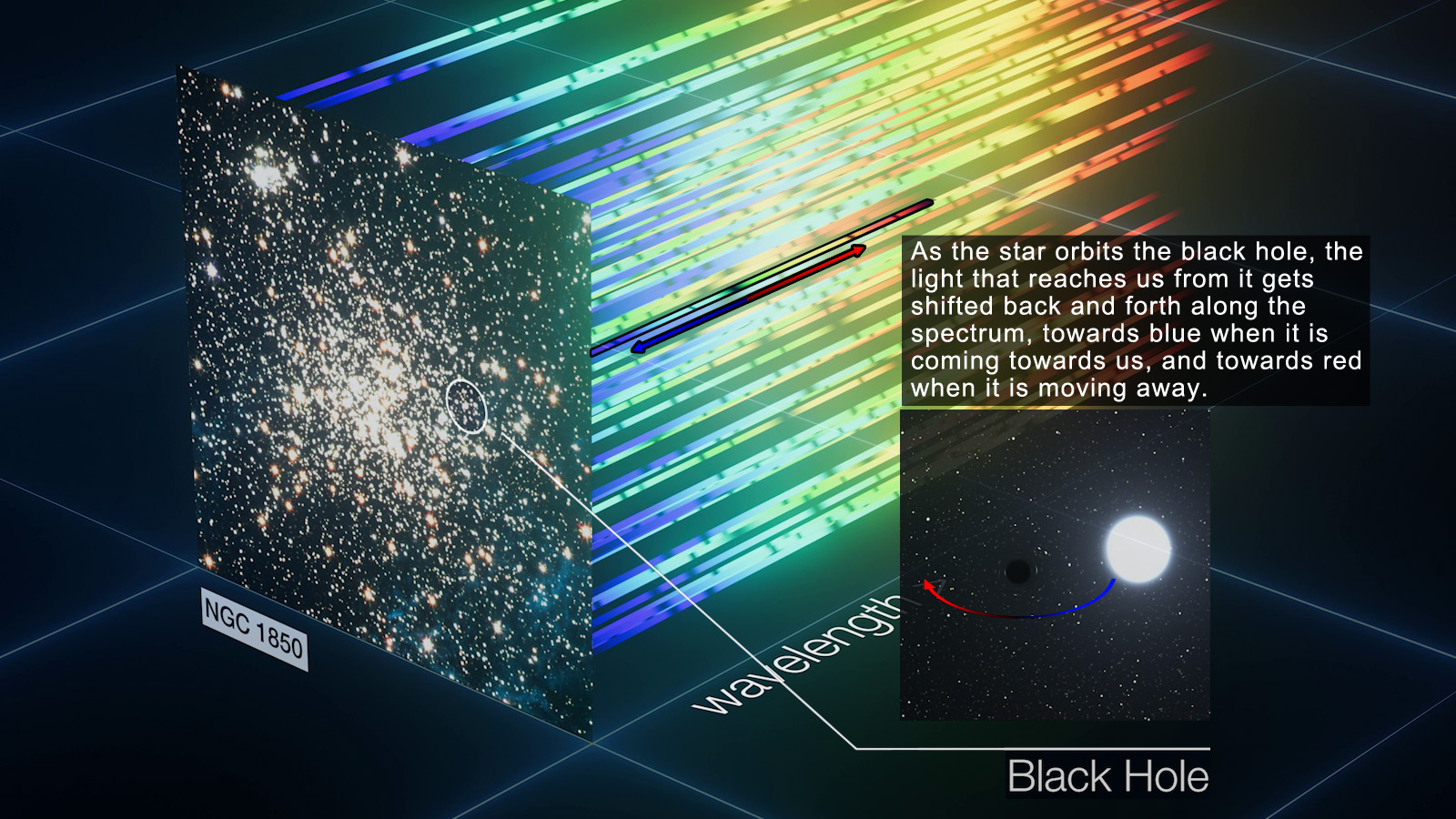

“MUSE allowed us to observe very crowded areas, like the innermost regions of stellar clusters, analyzing the light of every single star in the vicinity,” study co-author Sebastian Kamann, who is a veteran with MUSE at the Astrophysics Research Institute, said in the press release. “The net result is information about thousands of stars in one shot, at least 10 times more than with any other instrument.”

After closely observing the spectra of light emitted by all the stars in the cluster, one star among the thousands stood out. While the light from all the other stars remained relatively steady, the spectrum of the light from this one star changed, becoming more blue and then more red, in a regular pattern.

Finding no sign of a companion star, Saracino and her colleagues looked for other explanations. They found that the best match was a large blue star of about 5 solar masses orbiting around a black hole roughly 11 times more massive than the Sun. The black hole is now, appropriately, named NGC 1850 BH1 (short for NGC 1850 Black Hole #1).

In this case, although the black hole does have a binary companion, the star is not close enough to the black hole for an x-ray-emitting accretion disk to form. Instead, it was the companion star’s motion along its orbit that betrayed the black hole’s presence.

According to the ESO, this is the first black hole outside our galaxy to be found with this particular detection method. Using this method on star clusters in our own galaxy or in nearby galaxies could reveal more of these ‘hidden’ objects, leading astronomers to better understand how black holes form and evolve over time.

Source: The Weather Network

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.