Scientists who study extraterrestrial intelligence actually have a few questions about us.

Source: Esquire.com

Commander David Fravor of the U. S. Navy was behind the controls of a fighter jet over the Pacific Ocean in 2004 when he spotted something weird. It hovered over the water, churning it so forcefully that it appeared to be boiling. Moments later, the object accelerated away from him at a shocking speed. In 2015, another Navy pilot spied a fast-moving object at low altitude over the Atlantic. “What the fuck is that thing?” he radioed, a sentiment that basically everyone who heard about the two incidents shared.

What the fuck is that thing?

We’ve been wondering pretty much exactly that for as long as humans have walked the earth, searching for meaning and connection in the skies above us. But it’s lately reached a fever pitch, an almost wishful fervor. You might even say we’ve become obsessed.

Early this summer, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence released its long-awaited report on the topic of “What the fuck is that thing?” But it didn’t do much to explain away the UFOs that the Navy pilots encountered back in 2004 and 2015—or any of the 144 accounts the report took up. Here were the broad strokes: 1) The ODNI wants us to stop calling them UFOs and start calling them UAPs, or unidentified aerial phenomena, and 2) Those weren’t aliens. But if anyone thought the ODNI report would end speculation, boy, were they wrong. If anything, it just got us all wondering even harder: Are we alone in the cosmic void? Put more bluntly: Are aliens real?

Good luck getting a scientist to answer that for you with a yes or no. Claire Isabel Webb, a historian and anthropologist of science and a fellow at the Berggruen Institute, for example, answered like this: “Based on what we know about earth’s biochemistry and the profusion of life here, the deluge of exoplanet detection in the last three decades that tells us that most stars have planets, and a new understanding of ‘weird’ life-forms on earth that hints to all kinds of exotic life-forms beyond it, scientists now think it is very probable that extraterrestrial life exists elsewhere in the universe, perhaps even in our local solar system.”

Translation, we think: Yeah, there are probably aliens out there.

Whether this is news that fills you with dread or hope, it almost certainly conjures an image. Out of our timeless, cosmic loneliness, we’ve generated hosts of guesses about aliens: gray creatures with large black eyes; beings with long, tendril-like fingers; or ominous yet tender, intelligent entities. We’ve come up with generous creatures sharing the advanced knowledge of a wiser and kinder civilization. From The Twilight Zone to Arrival, these giving, selfless beings willing to save us are our best hope. There are also the evil ones, lacking in empathy, ready to colonize and to kill. However we imagine fellow sentient life, it usually shows up as some metaphor for humans as we know ourselves. This is actually more key to the search for extraterrestrial life than we might think.

Humans are on the lookout for intelligent life that feels familiar to us—that has some recognizable traits. Webb points out that the word alien simply means stranger. “It implies someone who is knowable but not known,” she says. We don’t just want to find alien life; we want to find someone we can have a conversation with, perhaps even someone who can help us. Maybe our renewed itch for neighbors comes at a time when we are longing to be saved, not just from the fate of human life but from ourselves. As I wrote this essay, two billionaires found earth so unsatisfactory that they launched themselves off the planet, and forest fires burned 400,000 acres of wilderness in Oregon, producing a haze that traveled all the way to New York City, blurring out the sun.

So perhaps a better question than whether we’re alone is what would make us feel less alone. Would confirmation of the existence of little green men do it? If we found a planet covered in whales or ladybugs or a planet that had only trees and birdlike creatures, would that? “I don’t think any of those things is really going to give us the satisfaction that we get in a sci-fi film,” says Jason Wright, a professor of astronomy and astrophysics and the director of the Penn State Extraterrestrial Intelligence Center. Even in the 1997 Jodie Foster movie Contact, the film’s aliens disguise themselves in human form to make their meet and greet less terrifying.

What if we can’t recognize aliens? What if they aren’t even “beings” the way we think of them? What if we detect a signal from an artificially intelligent robot designed to continuously send out radio waves in all directions? Would we feel contacted? Would we even identify it as intelligent, according to our definitions? Would we consider it “life” at all?

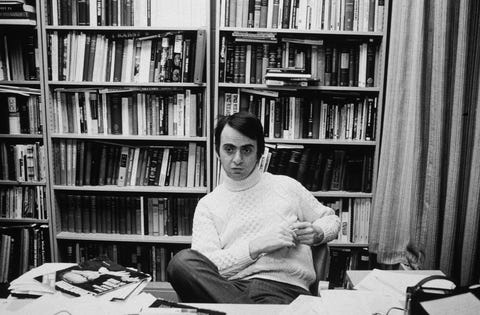

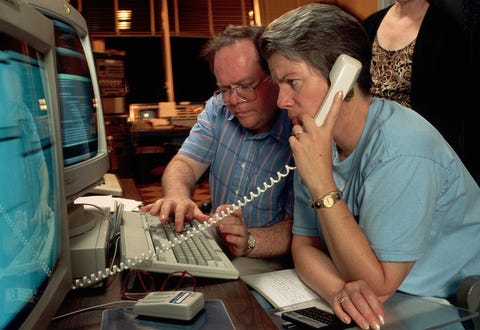

Okay, let’s assume we’re somehow able to overcome our earthly prejudices toward life that looks, acts, and uses technology in a way that’s recognizable to us. We still have the not insignificant problem of finding that life. Enter the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, often abbreviated SETI. If that acronym sounds familiar, it might be from Contact. (In case you haven’t seen it, know that it’s a great flick.) In 1984, astronomer Jill Tarter (on whom Foster’s character in Contact was based) and Thomas Pierson founded the SETI Institute, which is on the hunt for intelligent life. By that they mean life in the universe that looks like what humans would consider intelligent life. That could be just about anything, ranging from a human being to a whale. NASA briefly studied this in the ’80s, but since then it has spent much of its time focused on the discovery of microorganisms, either dead or living, in our solar system. It’s a worthy hunt, but we’re going to set that aside here, since our species would generally have trouble considering microorganisms intelligent.

“SETI is looking specifically for technology,” says Wright. “We’re looking for something that can use tools . . . or send signals in some way that would be detectable at interstellar distances. It seems like kind of a tall order, except we do it all the time.” He’s talking about the fact that we’ve sent every radio strain of the Rolling Stones and Beyoncé and almost every television transmission out into space. Scientists call these electromagnetic signals “technosignatures,” and they’re filling our local cosmos with evidence that we are here in the form of a pretty wild playlist. Even though we haven’t sent out many purposeful “Hey, we’re right here!” signals directly to other stars, we’ve still been broadcasting our existence into space for quite a while.

Until we learn to communicate instantaneously across space-time, this is more or less the only way to get in touch with our presumed neighbors in the universe. It’s entirely possible someone or something else is doing the same thing. But we’ll only know if we listen.

There’s another problem: Those supposed aliens might have rendered themselves extinct by the time our messages reach them. When an entire species removes itself from the evolutionary running, scientists attribute that to the Great Filter. (Climate change and devastating nuclear war are examples of this phenomenon of self-destruction.) If we found artificially intelligent life, it would also have had to survive the Great Filter. (“They would need to be programmed to not attack each other,” Webb explains.) This is not something our species has mastered. To progress past the technological threshold where we can travel deeper into space or build intelligent robotic surrogates to do it in our stead, we must not just survive but become more like the savior version of the aliens we’ve envisioned.

Are those saviors out there? “The fact that we have no idea means we’ve got to look,” says Wright. “We are working on it. I don’t think it’s going to go the way we all imagined. But really, we’re just getting started.” Contact supplies something of an answer when a girl who will grow up to be a SETI scientist and her father are discussing how far away all of the planets are. “Dad,” she says, “do you think there’s people on other planets?” He considers and replies, “If it is just us, seems like an awful waste of space.”

The often unspoken goal of these search efforts is a greater appreciation for the preciousness of our existence. On the one hand, our cosmic loneliness can make us feel isolated and vulnerable. There are two trillion galaxies in the universe: We couldn’t possibly be alone in the cosmos—could we? But on the other hand, isn’t it special to think our species has evolved to be able to venture out and explore our place in the grandness of things? Surely that’s something only we could ever do. The tragedy of our search for company in the cosmos is that the distances between stars mean that even if we did hear a signal, the conversation—both the interpretation of the message and the small matter of what to say back—could take decades. If it ever happens, though, it will be the most complex and most patient conversation in human history.

Until then, SETI calls it the search for a reason. Our universe is a big place, unfathomably big, and, statistically speaking, it’s very unlikely that we are the only technologically advanced tool users who are asking this question: Is it just us out here? There is probably “life” all over the cosmos. But even if there is life that can harness radio waves or has evolved as we have, there’s a danger that we won’t be able to recognize it. The search, in other words, is not only out there but down here. The answer is nothing less than rethinking what we’ve assumed life is. And the stakes are high. We can laugh off our UFO—sorry, ahem, UAP—obsession or we can actually search, not just for the universe’s signals but for our own. Our fears are telling us something. Our search for saviors is, too. We ought to listen.

Source: Esquire.com

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.