It has been 176 years since the 1845 Franklin Northwest Passage expedition, and its catastrophic outcome — the loss of the discovery ships HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, and all 129 officers and crew — continues to fascinate.

Source: The Conversation

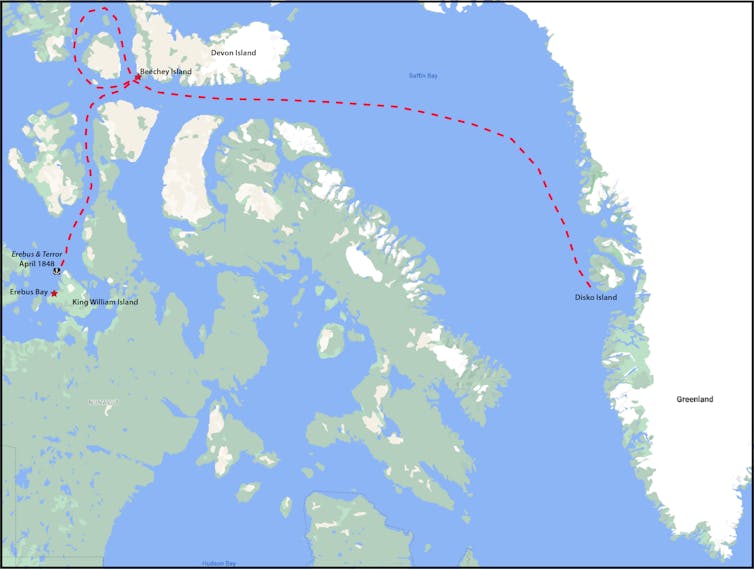

Three years into the attempt to transit the last uncharted section of a Northwest Passage through Arctic North America, 24 men, including John Franklin, had already died. For 19 months, both ships had been immobilized by impenetrable sea ice near King William Island. On April 22, 1848, the 105 surviving officers and crew left the ships and set out on a long and perilous journey over ice and land to reach aid hundreds of kilometres to the south.

None would survive, but the evidence of their lives and deaths has been found in archeological sites scattered along the route of their attempted escape on the Arctic shores where the final act of the tragedy played out.

Positive identification

Bones can provide information about age, height and health, but not the identities of the remains. The ability to confidently identify the remains can shed important light on mortality rates by rank, ship and location — details that might yield valuable insights about the decisions and events that played out during the final months of the expedition. It would also provide information for the sailors’ descendants, nearly all of whom know little, if anything, about the place or circumstances of their ancestor’s death.

A study we published in Polar Record, combining archeology, genealogy and DNA analysis, has provided the very first positive identification of the remains of one of the 105 sailors who departed Erebus and Terror in April 1848.

We applied DNA analysis to skeletal remains from the Franklin expedition by analyzing mitochondrial DNA, which is passed down through the maternal line, and Y-chromosome DNA, passed down from father to son. Analysis of 41 tooth and bone samples from nine Franklin archeological sites on King William Island yielded DNA profiles for 27 men.

DNA and genealogy

Next, we reached out to direct descendants of Franklin expedition members whose DNA could potentially match one of the 27 archeological profiles. The task of finding descendants was challenging, because for DNA to be useful in identifying an ancestor’s remains the descendant needed to be related in one of two very specific ways to the sailor: either a direct descendant in the female line traced through the Franklin sailor’s mother, or a direct descendant in the male line from the Franklin sailor himself or his father.

Seventeen such descendants provided DNA samples for the study; the results from the first 16 did not match any of the archeological DNA profiles but the 17th, from a great-great-great grandson of Warrant Officer John Gregory added link, living in South Africa, did.

John Gregory was an engineer by profession, had never been to sea, and was employed by a London manufacturer of steam engines and boilers. This must have been an exciting career because the very first passenger railway had started only 15 years before. His reasons for accepting a last-minute, multi-year assignment on an Arctic expedition are unknown, but might have included the generous monthly salary of 13 pounds — double the normal pay of first class engineers — and the excitement of being involved in a Royal Navy voyage of discovery.

On July 9, 1845, Gregory was aboard HMS Erebus anchored off Disko Island, Greenland. By all accounts, the ship’s companies were in high spirits, and making final preparations before sailing west into Lancaster Sound and into an uncertain but hopeful future. Letters written to loved ones, including one from Gregory to his wife Hannah, were carried back to Britain by the transport vessels that had accompanied Erebus and Terror to Greenland. It was the last letter that she would ever receive from him.

Travel routes

The DNA results allowed us to reconstruct some of the details of Gregory’s journey from where he penned Hannah’s letter to where he drew his final breath, 2,200 kilometres away on the desolate southwest shore of King William Island.

Gregory survived the first three years of the expedition and was one of the 105 men who left the ships on April 22, 1848, pulling ships’ boats mounted on sledges with the plan to reach the mainland and then sail them upriver that summer to the nearest trading post. He would have reached Erebus Bay, 75 kilometres south, sometime in early May, but he could go no further. Years later, searchers would find the skeletons of three men in and around a ship’s boat on a sledge. We now know that one of the men was John Gregory.

Archeological and DNA analyses have revealed for his descendants where John Gregory died, approximately when he died and that he did not die alone. His remains and those of his two companions now rest in a commemorative cairn erected in their memory at the site.

Source: The Conversation

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.