More than a year into a very real crisis, experts gathered virtually to confront a second emergency, a potential asteroid impact — but this disaster, fortunately, was entirely hypothetical.

Source: Space.com

Every two years, as part of the International Academy of Astronautics’ Planetary Defense Conference, scientists and emergency response personnel gather to discuss a made-up asteroid threat from discovery to impact. During this year’s exercise, which unfolded online from April 26 to April 28, the scenario presented an impact just six months away, a pointed reminder that limited lead time is a key weakness in our asteroid defense systems.

“The best solution to this scenario is not to get into it in the first place,” Lindley Johnson, NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Officer, said during the hypothetical scenario.

Johnson and other planetary defense experts, who focus on the threat posed by near-Earth asteroids and comets, rely on a host of techniques to ensure that Earth has nothing to fear from the thousands of space rocks that rattle our planet’s neighborhood.

First, there’s the matter of identifying as many objects as possible, tracking their orbits as precisely as possible and understanding how large they are. The vast majority of the near-Earth asteroids and comets scientists have identified — more than 25,000 to date — pose no threat at all to Earth. These objects never end up crossing Earth’s orbit with the required timing, or they’re so small that they would safely burn up as they plummeted through our planet’s protective atmosphere.

But large size and close proximity to Earth is a combination that makes planetary defense experts uncomfortable. So far, as scientists have gathered progressively sharper observations of these space rocks, in every case the threat has faded as those additional measurements confirm that the object will stay a safe distance from Earth.

That’s great news for those of us living on the planet, of course. But planetary defense experts want to practice what to do if our luck runs out, to make sure we humans have the best chance to protect ourselves.

Hence, hypothetical asteroid exercises, the planetary equivalent of a fire drill.

For the Planetary Defense Conference exercises, a team of scientists at NASA and elsewhere pull the alarm by creating a fictional asteroid around which to build a scenario. Over the course of a few days, the team reveals additional pieces of information, just as if the real discovery and tracking process were unfolding.

Along the way, the full range of planetary defense community members — from asteroid scientists and lawyers to spacecraft engineers and emergency response personnel — think through what challenges they would face, what choices they would make, and what information or plans they wish they had.

Meet this year’s fake asteroid

Because the scenario is meant to push the field of planetary defense ahead, the team behind the hypothetical asteroid works hard to make the situation as grim as possible: if something can go wrong, it usually does. This year’s scenario played out accordingly, as scientists announced they had observed the fake asteroid with just six months’ notice before the potential impact scenario on Oct. 20, 2021, a remarkably short timescale.

(You can follow along in the original scenario materials, which are posted on the website of NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies, which is home to planetary defense expert Paul Chodas, who led the team designing the hypothetical asteroid.)

Initial asteroid detections often include lots of uncertainty, and that’s definitely the case for this made-up space rock, which the team dubbed 2021 PDC. Those first observations tell scientists only that it’s somewhere between 100 feet and 2,300 feet across (35 to 700 meters) — anywhere from about half the wingspan of a 747 airplane to approaching twice the height of the Empire State Building.

At the very first sighting, there’s only a 1 in 2,500 chance that 2021 PDC will hit Earth, but within a week, additional observations have increased that risk to 1 in 20, the level that international organizations have marked as warranting concern.

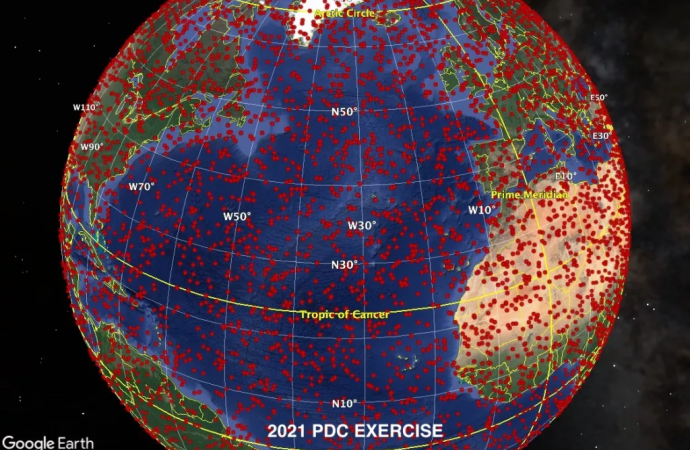

But with only a week of observations, scientists have no idea where the asteroid might hit if it does indeed collide with Earth — pretty much the entire planet except Antarctica and Australia are at risk based on these measurements.

“In view of the dramatic, drastic consequences of an impact, I think there would be a demand … ‘Why can’t we be certain if it’s going to hit or if it’s not going to hit?'” Chodas said. “This period of uncertainty will cause perhaps a lot of distrust, frankly, of the technical experts as we tried to explain our level of uncertainty and the fact that we’d be doing our best to try to figure out whether it’s going to hit or not.”

In some ways, that’s good news: Lots of potential impact scenarios would see 2021 PDC exploding harmlessly over an ocean. In fact, at this point in the recent exercise, the asteroid has a whopping 97% chance of causing no damage. The 3% is what worries the experts, since these scenarios could see tens of millions of people impacted by the event.

“We can see right off the bat that we are faced with a very challenging scenario here,” Lorien Wheeler, an engineer at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California who specializes in advanced simulation techniques, said during the exercise, “one that could threaten almost any region of the world and one that combines a high likelihood of causing no damage with a small chance of causing extremely catastrophic levels of damage.”

So with a high probability of little damage but a small chance of serious destruction, how worried would you be?

A frantic search for more data

The only way to reduce all that uncertainty is to acquire more observations that could hone scientists’ estimates of the asteroid’s orbit or size. And there are a plethora of options to try.

First, look in archived observations to see whether asteroid survey programs have caught 2021 PDC before without the detection being strong enough to notice. That process, called “precovery,” can happen fairly quickly.

In the case of this hypothetical asteroid, the orbital trajectory based on initial data suggests that the asteroid was last near Earth in 2014, so scientists turned to the archives. Within a week of time unspooling in the scenario, they snagged some observations from that time in which the asteroid appeared too faint to identify but could be spotted once scientists knew what to look for.

Combining that “precovery” data with the initial detection, the scientists recalculate the made-up asteroid’s orbit, which takes a collision with Earth from a 1 in 20 chance to a sure thing. The extra data is even enough to identify a swath of central Europe from the Arctic Circle to Egypt where the asteroid might hit.

It’s bad news, of course, but helpful to know, and motivation to ask whether there’s anything humans can do to keep the asteroid from hitting Earth.

Here’s where the short time frame gets uncomfortable. Planetary defense experts consider a few techniques for keeping a threatening asteroid away. One is to slam something heavy into the space rock to push it forward or backward along its orbital trajectory. Although the asteroid’s orbit would still intersect with Earth, the two objects would no longer reach that point simultaneously, preventing a collision.

Another option is to deliver a nuclear device that would vaporize part of the asteroid and push the rest of the rock away from the explosion.

But neither of these techniques matches well with our current slow-and-steady approach to launching spacecraft missions. With just six months’ warning before an impact, humans would essentially need to have a spacecraft sitting on a launchpad, ready to go after a newly discovered asteroid.

“Rapid launch capabilities to actually launch spacecraft in a short-warning scenario like this are not currently available,” Brent Barbee, who led the analysis of potential missions, said during the scenario. Most interplanetary missions need about five years to get from approval to launch, he noted. “It’s much better to find these objects as far in advance as possible of their Earth-impact dates, which makes it much easier for us to deal with them using spacecraft missions.”

The same challenge holds for a mission that could visit the space rock directly to give emergency response personnel a better estimate of the object’s size, and hence how much damage it could cause. Such a mission might also further hone scientists’ calculations of where precisely on Earth the asteroid will hit to a scale that emergency response personnel can work with more easily.

If, that is, it were possible — which means either having spacecraft on call or having more lead time. The precovery data is a taunting reminder of that latter option: With stronger survey technology active in 2014, scientists might have avoided this hypothetical six-month scenario entirely.

Brace for impact

Time for a little something to go right, don’t you think?

After a string of bad news, the team behind the hypothetical scenario threw humans a bit of good luck: Thanks to a two-month observing campaign using high-power telescopes on the ground and in orbit, scientists track down a few extra crumbs of data about the made-up asteroid.

One set of those observations hones the orbital calculations enough to narrow the range of possible impact zones to a swath crossing Germany, the Czech Republic and Austria. Another clarifies the size of the object: Instead of the massive range of possibilities, scientists now think 2021 PDC is perhaps between 260 feet and 790 feet (80 to 240 m) wide — still large enough to do real damage, but now eliminating the very worst scenarios scientists had previously been considering.

But now there are only four months before the hypothetical impact, and there’s still nothing to be done about the asteroid itself. All that’s left to do is keep hoping for better observations and begin preparing the region to survive the impact.

“Now we are faced with a short-warning emergency response situation in which we still have a large amount of uncertainty about the object’s size and potential damage ranges,” Wheeler said.

Fortunately, the geography helps narrow down scenarios. With the new size and impact zone, scientists can simulate thousands of potential impacts with different characteristics to understand the potential scope of damage. That offers insights that could guide a response strategy, she said.

“Another important thing to note about our worst case here is that it is not centered over a high-population city; instead it is centered in between the larger cities such that the outer damage levels span multiple higher-population regions,” Wheeler said. “So when you envision the worst-case scenario, keep in mind that it may not be a direct strike right over the biggest city in the region, like you might expect.”

In the end, though, the planet wasn’t faced with the worst-case scenario in the conference exercise. Measurements taken less than a week before impact show the object is about 340 feet (100 m) across, smaller than many of the potential scenarios, and is headed toward a fairly quiet patch of forest nestled between Prague and Munich.

Planetary defense informed by a pandemic

But in the hypothetical exercise, it’s not so much about where the made-up asteroid actually ends up as the discussions people have along the way. Particularly key to the exercise is bringing together emergency management experts, whose daily focus is a bit more pedestrian than incoming space rocks, with the scientists who are used to thinking about the potential of an asteroid impact.

Inevitably, the COVID-19 pandemic was front of mind as experts considered the communication struggles around an uncertain but dangerous situation.

“I think that in the context of COVID, if this was to happen now, it would be very natural for decisionmakers to look at the worst-case scenario,” said Miguel Roncero Martin of the European Union Emergency Response Coordination Centre. “Why? Because COVID has shown that the worst-case scenario can really happen.”

Experts pointed to painfully fresh examples of the difficulties of evaluating uncertain risks and communicating that information to the public. “We’ve seen the spread of misinformation during this pandemic, whether it’s the conspiracy theories about COVID-19 — does it exist at all? — right up to today — anti-vaxxers, vaccine hesitation and so on,” Martin Nesirky, director of the United Nations’ Information Service said.

“You need a common voice who can speak on behalf of the system, if you like,” he said. “Who’s going to be the Dr. Tedros?” (That would be Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the director-general of the World Health Organization who led much of the global communication as the COVID-19 pandemic was emerging in early 2020.)

And, like COVID-19, a serious asteroid impact would require a host of serious interdisciplinary conversations.

“If a whole area is destroyed, there will be economic consequences,” Tom De Groeve, Deputy Head of the Disaster Risk Management Unit at the European Commission Joint Research Centre, said during the exercise. “In the COVID situation, these were initially a bit underestimated, and it was very, very difficult to link the communities — the economic modelers and physical modelers.”

And of course, there’s no reason to think that the pandemic will no longer be a factor by the time of the hypothetical asteroid impact. “We really miserably failed in understanding its [COVID’s] impact on second waves coming, and a third wave has come in Europe already, and what would be the situation by the time this impact happens — will it be a fourth wave?” said Shirish Ravan, a program officer at the U.N.’s Space-based Information for Disaster Management and Emergency Response.

“This comes once in 100 years; a pandemic comes once in 100 years, but we are facing it now,” Ravan said. “Now it is a good time to tell them [national leaders] that some disasters might come once in 100 years, but we need to have that vision to prepare for it and respond to it and mitigate it.”

Source: Space.com

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.