Source: Phys.org Scientists working with data from the Sloan Digital Sky Surveys’ Apache Point Observatory Galactic Evolution Experiment (APOGEE) have discovered a “fossil galaxy” hidden in the depths of our own Milky Way. This result, published today in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, may shake up our understanding of how the Milky Way

Source: Phys.org

Scientists working with data from the Sloan Digital Sky Surveys’ Apache Point Observatory Galactic Evolution Experiment (APOGEE) have discovered a “fossil galaxy” hidden in the depths of our own Milky Way.

This result, published today in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, may shake up our understanding of how the Milky Way grew into the galaxy we see today.

The proposed fossil galaxy may have collided with the Milky Way ten billion years ago, when our galaxy was still in its infancy. Astronomers named it Heracles, after the ancient Greek hero who received the gift of immortality when the Milky Way was created.

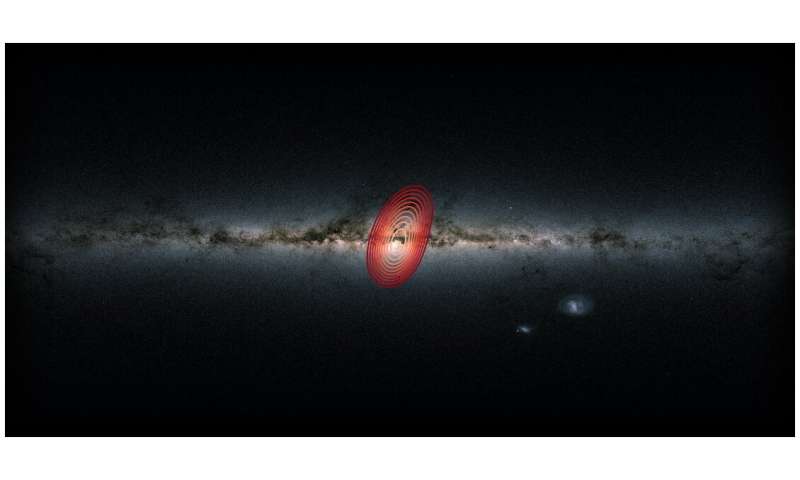

The remnants of Heracles account for about one third of the Milky Way’s spherical halo. But if stars and gas from Heracles make up such a large percentage of the galactic halo, why didn’t we see it before? The answer lies in its location deep inside the Milky Way.

“To find a fossil galaxy like this one, we had to look at the detailed chemical makeup and motions of tens of thousands of stars,” says Ricardo Schiavon from Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) in the UK, a key member of the research team. “That is especially hard to do for stars in the center of the Milky Way, because they are hidden from view by clouds of interstellar dust. APOGEE lets us pierce through that dust and see deeper into the heart of the Milky Way than ever before.”

APOGEE does this by taking spectra of stars in near-infrared light, instead of visible light, which gets obscured by dust. Over its ten-year observational life, APOGEE has measured spectra for more than half a million stars all across the Milky Way, including its previously dust-obscured core.

Graduate student Danny Horta from LJMU, the lead author of the paper announcing the result, explains, “examining such a large number of stars is necessary to find unusual stars in the densely-populated heart of the Milky Way, which is like finding needles in a haystack.”

To separate stars belonging to Heracles from those of the original Milky Way, the team made use of both chemical compositions and velocities of stars measured by the APOGEE instrument.

“Of the tens of thousands of stars we looked at, a few hundred had strikingly different chemical compositions and velocities,” Horta said. “These stars are so different that they could only have come from another galaxy. By studying them in detail, we could trace out the precise location and history of this fossil galaxy.”

Because galaxies are built through mergers of smaller galaxies across time, the remnants of older galaxies are often spotted in the outer halo of the Milky Way, a huge but very sparse cloud of stars enveloping the main galaxy. But since our galaxy built up from the inside out, finding the earliest mergers requires looking at the most central parts of the Milky Way’s halo, which are buried deep within the disc and bulge.

Stars originally belonging to Heracles account for roughly one third of the mass of the entire Milky Way halo today—meaning that this newly-discovered ancient collision must have been a major event in the history of our galaxy. That suggests that our galaxy may be unusual, since most similar massive spiral galaxies had much calmer early lives.

“As our cosmic home, the Milky Way is already special to us, but this ancient galaxy buried within makes it even more special,” Schiavon says.

Karen Masters, the Spokesperson for SDSS-IV comments, “APOGEE is one of the flagship surveys of the fourth phase of SDSS, and this result is an example of the amazing science that anyone can do, now that we have almost completed our ten-year mission.”

And this new age of discovery will not end with the completion of APOGEE observations. The fifth phase of the SDSS has already begun taking data, and its “Milky Way Mapper” will build on the success of APOGEE to measure spectra for ten times as many stars in all parts of the Milky Way, using near-infrared light, visible light, and sometimes both.

Source: Phys.org

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.