For tens of thousands of years, a Neanderthal molar rested in a shallow grave on the floor of the Stajnia Cave in what is now Poland. For all that time, viable mitochondrial DNA remained locked inside – and now, finally, scientists are discovering its secrets.

Source: Science Alert

Labelled Stajnia S5000, the tooth belonged to a Neanderthal who lived at least 80,000 years ago, according to the new analysis. Which means the individual was alive during a pivotal time of environmental upheaval in Neanderthal history.

The landscape of central-eastern Europe underwent quite a dramatic transformation around 100,000 years ago, during the Middle Palaeolithic.

The world was in the grip of an ice age known as the Last Glacial Period, and the Neanderthal habitats of northwestern and central Europe changed from rich forests to frigid taigas and steppes. These were more welcoming to the woolly mammoths, woolly rhinos, and reindeer adapted to chilly Arctic conditions – but much more challenging for the Neanderthals.

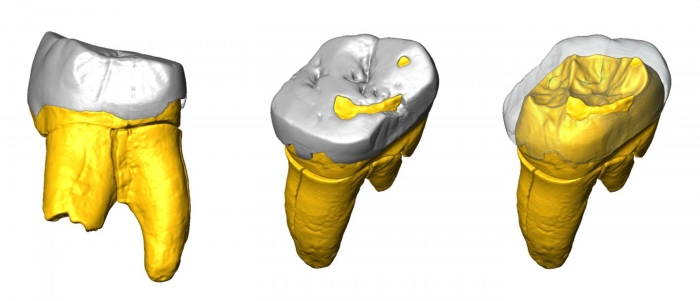

A digital model of Stajnia S5000. (Stefano Benazzi)

A digital model of Stajnia S5000. (Stefano Benazzi)

As regions froze, Neanderthal populations shrank, only to return again as temperatures fluctuated back towards warmer, in a temporary amelioration of the glaciation (the actual ice age wouldn’t end until about 11,700 years ago), characterised by extreme seasonal changes and low biomass. In other words, the seasons were wild, and food was scarce.

It was during one of these periods – known as Marine Isotope Stage 5a (MIS 5a) that began about 82,000 years ago – that the Altai Neanderthals in Central Asia were replaced by populations of western European Neanderthals.

But, even as many European Neanderthals fled for more temperate environments, a specific type of tool style categorised as Micoquian was in use in the frozen environments of what is now eastern France, Poland and Caucasus – suggesting that some Neanderthals were able to adapt to their changing world.

“Poland, located at the crossroad between the Western European Plains and the Urals, is a key region in understanding these migrations and for solving questions about the adaptability and biology of Neanderthals in periglacial habitat,” said archaeologist Andrea Picin of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany.

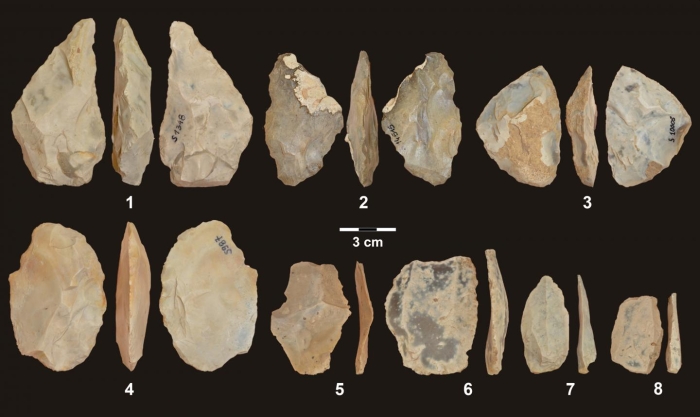

Micoquian tools first started appearing in central and eastern Europe about 130,000 years ago – a little before European Neanderthals started replacing the Central Asian populations.

These artefacts – some of which have been found in Stajnia Cave – are characterised by bifacial shaping, asymmetrical shapes and leaf shapes, and they’re only found in regions where woolly mammoths and woolly rhinos roamed, suggesting they were specifically adapted for hunting and foraging in such landscapes.

Micoquian tools from Stajnia Cave. (Andrea Picin)

Micoquian tools from Stajnia Cave. (Andrea Picin)

There are a few other clues that suggest a changing survival strategy. The cave itself, the researchers believe, has too narrow an opening to be useful as a permanent settlement. However, groups of Neanderthals could have used it as a temporary camp during foraging trips.

And there’s the tooth itself. Its shape is consistent with Neanderthal teeth, and the wear suggests an adult tooth. The genetic analysis of the softer tissue preserved inside the protective outer shell of hard enamel was especially revealing.

Firstly, it allowed archaeologists to date the tooth, placing it squarely in MIS 5a.

“We were thrilled when the genetic analysis revealed that the tooth was at least ~80,000 years old,” said archaeologists Wioletta Nowaczewska of Wroclaw University and Adam Nadachowski of the Polish Academy of Sciences. “Fossils of this age are very difficult to find and, generally, the DNA is not well preserved.”

And secondly, it allowed them to trace the closest relatives of the tooth’s owner.

“We found that the mitochondrial genome of Stajnia S5000 was closest to the one of a Mezmaiskaya 1 Neanderthal from the Caucasus,” said archaeologist Mateja Hajdinjak of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. And the DNA was, surprisingly, more distantly related to two other Neanderthals that died in Belgium and Germany around 120,000 years ago.

Along with the tools, which have been found at several key sites, including Northern Caucasus, Germany, Altai and Crimea, the tooth suggests that the Neanderthals of northern and eastern Europe became much more migratory, chasing the migratory Arctic animals across the continent as a new survival strategy.

This would explain, the researchers said, just how the Micoquian tools were so widespread, and how they remained in continuous use across these regions for over 50,000 years.

“The Stajnia S5000 molar is truly an exceptional find that sheds light on the debate over the wide distribution of the Micoquian artefacts,” Picin said.

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.

Source: Science Alert

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.