A team of biologists from Japan and the United States has successfully revived aerobic microbes found in 101.5-million-year-old sediments from the abyssal plain of the South Pacific Gyre, the part of the ocean with the lowest productivity and fewest nutrients available to fuel the marine food web.

Source: Sci News

“Our main question was whether life could exist in such a nutrient-limited environment or if this was a lifeless zone,” said lead author Dr. Yuki Morono, a researcher in the Kochi Institute for Core Sample Research and the Research and Development Center for Submarine Resources at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC).

“And we wanted to know how long the microbes could sustain their life in a near-absence of food.”

On the seafloor, there are layers of sediment consisting of marine snow (organic debris continually sourced from the sea surface), dust, and particles carried by the wind and ocean currents. Small life forms such as microbes become trapped in this sediment.

Aboard the drillship JOIDES Resolution, Dr. Morono and colleagues drilled numerous sediment cores 100 m (328 feet) below the seafloor and nearly 6 km (3.7 miles) below the ocean’s surface.

The scientists found that oxygen was present in all of the cores, suggesting that if sediment accumulates slowly on the seafloor at a rate of no more than 1-2 m (3.3-6.6 feet) every million years, oxygen will penetrate all the way from the seafloor to the basement.

Such conditions make it possible for aerobic microorganisms to survive for geological time scales of millions of years.

With fine-tuned lab procedures, the authors incubated the samples, ranging from 101.5 to 4.3 million years ago, to coax their microbes to grow.

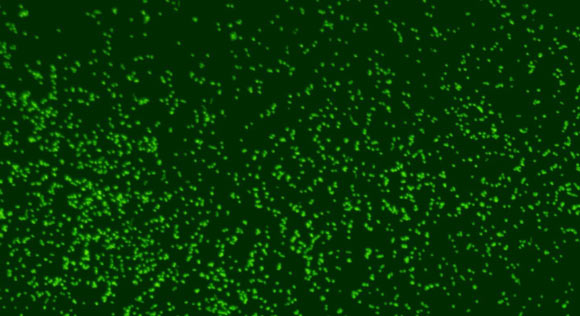

The results demonstrated that rather than being fossilized remains of life, the microbes in the sediment had survived, and were capable of growing and dividing.

The team also investigated the taxonomic composition of 6,986 individual cells they revived and found that the microbial communities were dominated by bacteria.

Dominant bacterial groups included Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, and Deltaproteobacteria, with a minor fraction of Chloroflexi. A small fraction of thermophilic Archaea was detected only in one young sample.

“At first I was skeptical, but we found that up to 99.1% of the microbes in sediment deposited 101.5 million years ago were still alive and were ready to eat,” Dr. Morono said.

“We knew that there was life in deep sediment near the continents where there’s a lot of buried organic matter,” added senior co-author Professor Steven D’Hondt, a researcher in the Graduate School of Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island.

“But what we found was that life extends in the deep ocean from the seafloor all the way to the underlying rocky basement.”

A paper on the findings was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: Sci News

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.