Astronomers have finally confirmed the existence of two exoplanets — Proxima b and c — orbiting Proxima Centauri, the Sun’s closest stellar neighbor and one of the best-studied low-mass stars.

Source: Sci News

Proxima Centauri, the smallest member of the Alpha Centauri system, is an M5.5-type star located 4.244 light-years away in the southern constellation of Centaurus.

The star has a measured radius of 14% the radius of the Sun, a mass of about 12% solar, and an effective temperature of only around 3,050 K (2,777 degrees Celsius, or 5,031 degrees Fahrenheit).

Proxima Centauri is 1,000 times less luminous than the Sun, which even at its close distance makes it invisible to the naked eye.

It has a very slow rotation of 83 days and a long-term activity cycle with a period of approximately 7 years. Its habitable zone ranges from distances of 0.05 to 0.1 AU.

The Earth-mass planet Proxima b was first discovered in 2016 by Queen Mary University of London astronomer Dr. Guillem Anglada-Escudé and co-authors.

The planet sits within Proxima Centauri’s habitable zone, where liquid water could theoretically exist on the surface.

“Confirming the existence of Proxima b was an important task, and it’s one of the most interesting planets known in the solar neighborhood,” said Dr. Alejandro Suarez Mascareño, an astronomer at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias and the Universidad de La Laguna and the lead author of a paper to be published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Dr. Mascareño and colleagues confirmed the presence of Proxima b using independent measurements obtained with the ESPRESSO (Echelle SPectrograph for Rocky Exoplanets and Stable Spectroscopic Observations), a high-resolution spectrograph installed on ESO’s Very Large Telescope.

Their results show that the minimum mass of Proxima b is 1.17 times that of Earth (the previous estimate was 1.3 Earth masses) and that it orbits around its star in only 11.2 days.

“ESPRESSO made it possible to measure the mass of the planet with a precision of over one-tenth of the mass of Earth. It’s completely unheard of,” said Nobel laureate Michel Mayor, professor emeritus at the University of Geneva and the ‘architect’ of all ESPRESSO-type instruments.

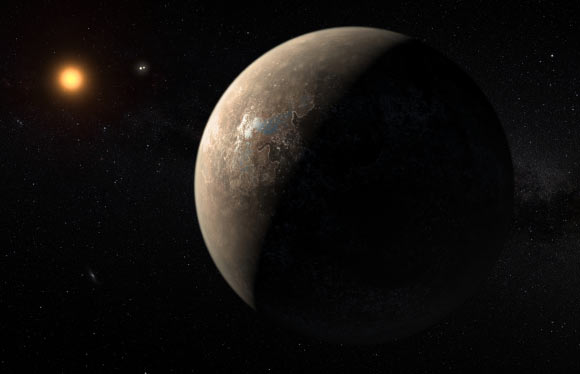

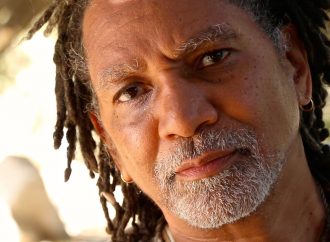

An artist’s impression of the Proxima Centauri system. Image credit: Lorenzo Santinelli.

Earlier this year, Dr. Mario Damasso from Italy’s National Institute for Astrophysics and colleagues announced they might have found a super-Earth exoplanet around Proxima Centauri.

The astronomers used radial velocity observations to deduce the candidate planet — named Proxima c — orbits the star every 1,907 days at distance of 1.5 AU. Still, its existence was far from certain.

In a separate study, Dr. George Benedict and Dr. Barbara McArthur from McDonald Observatory and the University of Texas at Austin revisited the 25-year-old Hubble data for Proxima Centauri.

“When we originally studied Proxima Centauri in the 1990s, we only checked for planets with orbital periods of 1,000 Earth days or fewer. We found none,” Dr. Benedict said.

“We now revisited that data to check for signs of a planet with a longer orbital period.”

Indeed, the team found a planet with an orbital period of about 1,907 days in the archival Hubble data.

This was an independent confirmation of the existence of Proxima c.

These images, taken by the SPHERE instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope, show the candidate optical counterparts of Proxima c (red circles); background stars are also shown. Image credit: Gratton et al, arXiv: 2004.06685.

Shortly afterward, Dr. Raffaele Gratton of INAF and colleagues published images of the planet at several points along its orbit that they had made with the SPHERE (Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet Research) instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope.

Dr. Benedict and Dr. McArthur then combined the findings of all three studies: their Hubble astrometry, Dr. Damasso’s radial velocity studies, and Dr. Gratton’s images to refine the mass of Proxima c.

They found that the planet is about 7 times as massive as Earth.

“Basically, this is a story of how old data can be very useful when you get new information,” Dr. Benedict said.

“It’s also a story of how hard it is to retire if you’re an astronomer, because this is fun stuff to do!”

Dr. Benedict and Dr. McArthur presented their results June 2 at the 236th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS).

A paper by Dr. Gratton’s team will be published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Source: Sci News

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.