New invasions are hitting just as growing season gets underway, threatening millions with hunger.

Source: National Geographic

“These…swarms…are terrifying,” Albert Lemasulani narrated breathlessly as he recorded a video of himself swatting his way through a crush of desert locusts in northern Kenya this April. The insects, more than two inches long, whirred around him in thick clouds, their wings snapping like ten thousand card decks being shuffled in unison. He groaned: “They are in the millions. Everywhere…eating…it really is a nightmare.”

Lemasulani, 40, lives with his family in Oldonyiro, where he herds goats that survive on shrubs and trees. He’d previously heard of locusts only from stories passed down in the community. That changed earlier this year when the largest invasion of the voracious insects in decades descended on East Africa. With their seemingly bottomless appetites, locusts can cause devastating agricultural losses. An adult desert locust can munch through its own bodyweight, about 0.07 ounces, of vegetation every day. Swarms can swell to 70 billion insects—enough to blanket New York City more than once—and can destroy 300 million pounds of crops in a single day. Even a more modest gathering of 40 million desert locusts can eat as much in a day as 35,000 people.

This is the worst “upsurge”—the category of intensity below “plague”—of desert locusts experienced in Ethiopia and Somalia for 25 years and in Kenya for 70 years. The region’s growing season is underway, and as the swarms have grown while the coronavirus complicates mitigation efforts, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates up to 25 million East Africans will suffer from food shortages later this year.

Some 13 million people in Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Djibouti, and Eritrea already suffer from “severe food insecurity,” according to the FAO, meaning they may go without eating for an entire day or have run out of food altogether.

“We fear for our future because these kinds of swarms will mean we don’t have anything to feed our animals,” Lemasulani says. Farmers are equally worried about their crops. “We pray God will clear the locusts for us. It’s as terrifying as COVID-19.”

In the beginning

Desert locusts flourish when arid areas are doused with rain, because they seek to lay their eggs in damp, sandy soil near vegetation that can sustain the young until their wings develop enough for the insects to forage farther afield.

Usually, when locusts have space to spread out, they actively avoid one another. But in favorable circumstances, desert locust populations can multiply 20-fold every three months. Crowding together as a result of this increased breeding triggers a behavior change. No longer loners, they turn into social or “gregarious” creatures, forming large swarms.

Recently, conditions for procreation and migration have been not just favorable—but ideal. In 2018 and 2019, a series of cyclones that scientists link to unusually warm seas rolled in off the Indian Ocean and soaked a sandy desert in the Arabian Peninsula known as the Empty Quarter. A locust boom followed.

Locusts move through several phases before maturing into flying adults. At any point in that process they can turn gregarious—if conditions are right. Transformations in their behavior and physical traits can eventually be reversed, or they can persist and be passed on to offspring.

“We often think of deserts as environments that are very harsh and low productivity, which they are a lot of the time,” says National Geographic grantee Dino Martins, an entomologist, evolutionary biologist, and executive director of the Mpala Research Centre in northern Kenya. The center is working to sequence the desert locust’s genome to to learn what environmental and genetic factors may prompt the locusts’ transformation from solitary to gregarious. “When [deserts] have the right conditions, they can flip, and you can move to a situation with lots of biological activity. That’s basically what we’re seeing now,” he says.

By June 2019, large swarms were on the move, traveling over the Red Sea to Ethiopia and Somalia. Aided by uncommonly heavy rains that buffeted East Africa from October to December, the insects spread south to Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania.

Since the locusts first reached East Africa, favorable breeding conditions have continued, and the swarms have expanded. “I can’t tell you if it’s by 20 times, but [the population] is much bigger,” says Cyril Ferrand, Resilience Team Leader for East Africa at the FAO, which monitors the desert locust situation globally.

When the first wave of locusts arrived in the region in late 2019, most of last year’s crops had reached maturity or been harvested. But the timing of the current, so-called “second generation”—an even more massive wave—is especially worrisome.

That’s because East Africa’s primary growing season begins around mid-March, and the emerging plants are particularly vulnerable to locusts, says Anastasia Mbatia, the technical manager of agriculture at Farm Africa, a charity that works with farmers, pastoralists, and forest communities in East Africa. “When [locusts] feed on the germinating leaves, the crop cannot grow,” she says. “Farmers would need to sow seeds again.” But a second planting in the weeks ahead likely would not be successful, as the best growing weather has already passed.

Spraying for relief

To stem the explosion of locusts, governments often spray pesticides—either from the air or directly on the ground. FAO’s Ferrand says sourcing such chemicals during the COVID-19 pandemic is a challenge. “We have had delays in supply. That means managing the [pesticide stocks] today is a very different reality because there are fewer planes moving globally,” he says.

Even more difficult in places such as Kenya that have little experience with gigantic locust invasions is deciding where to spray. Depending on the winds, which largely determine locust flight patterns, a swarm might travel 80 miles in a day. (In 1988, desert locusts were found to have crossed from West Africa to the Caribbean in just 10 days.)

To chase down these highly mobile swarms, the FAO is relying increasingly on information provided by local people, including Lemasulani, who began voluntarily tracking locust swarms in January.

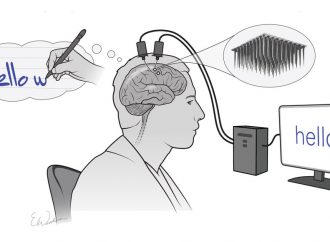

Drawing on an extensive network of contacts who call him when they spot pockets of the insects, Lemasulani hires motorbike taxis to speed him to swarms. When he finds them, he enters their coordinates in a mobile phone app called elocust3m that was released in late February by David Hughes and his colleagues at Penn State University’s PlantVillage program, an open access public resource for smallholder farmers. Hughes developed the app at the request of the FAO, whose field staff have operated a similar tracking program on specialized tablets since 2014. The data are then shared with the government, which can decide how best to react.

Until recently, when PlantVillage began paying him a stipend to cover his transport and telephone costs, Lemasulani paid for his locust scouting out of his own pocket. (His travels have been exempted from COVID-19 restrictions, as are training sessions for new elocust3m volunteers—residents in areas where swarms are expected—who nonetheless must wear masks and stay six feet apart.)

As Lemasulani wraps a red shawl around his shoulders to protect himself from the rain that has begun to fall outside his home, he says over video chat, “I come from a poor family background and got sponsored by the Catholic church in Oldonyiro though my primary and high school years. I was sponsored by a person I have never met. There is no way I can pay my sponsor back, but I feel noble giving back to my community.”

Source: National Geographic

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.