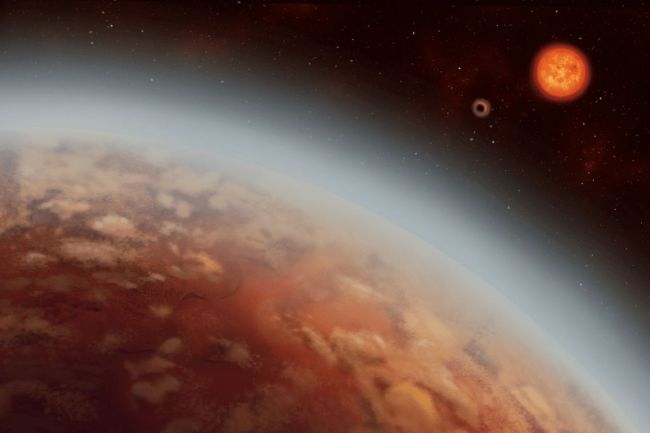

Three teams of astronomers have been fascinated by an alien world known as K2-18b. But what’s all the fuss about?

Source: Space.com

In September, two teams announced that they had found signs of liquid water in the planet’s atmosphere — a landmark discovery in the search for potentially habitable alien worlds. But the mere presence of water isn’t the only condition necessary for life. Other conditions, like temperature and pressure, can also affect a planet’s habitability. Now, a third team reports that the pressures of liquid water on the same world may be good for life to evolve — another intriguing development for scientists.

“We recognized pretty early on that this is a very unique target,” Björn Benneke, an astronomer at the University of Montreal, told Space.com. Benneke led one of the teams that announced the atmospheric analysis in the September 2019 study, which was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters in December. He presented the findings in January at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

Benneke and his colleagues used the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes to study K2-18b a dozen times over a three-year period, to collect precise observations of its atmosphere.

Although scientists have studied exoplanet atmospheres before, those worlds have been larger than K2-18b, which is only about 2.6 times the size of Earth and 8.5 times its mass. The planet’s small size made the observations especially challenging, requiring multiple detailed measurements that, combined, could provide a more in-depth probe of the world.

“Nothing like this has been done before,” Benneke said.

“Similar to Earth”

K2-18b is 110 light-years away, in the constellation Leo,where it orbits a small but active type of star that can hurl bursts of radiation at orbiting planets. Although the star is smaller and dimmer than the sun, K2-18b’s 33-day orbit means the planet receives roughly the same amount of energy from its star as Earth receives from the sun.

The star’s small size makes it easier to detect details of a diminutive planet like K2-18b because observations of a planet depend on how much light it blocks as it passes in front of its star from Earth’s perspective. A smaller planet blocks less light than a larger one, but a smaller star has less light to block, making that small signal somewhat easier to see. (The planet’s orbit also helped scientists capture multiple passes across its star.)

In the Hubble and Spitzer observations, Benneke and his team found the signature of water in the exoplanet’s atmosphere — and not just any form of water. “Even more exciting, we discovered in the data that there’s a cloud deck on the planet,” Benneke said.

The clue was that starlight beaming through the atmosphere came to an abrupt stop at a certain altitude. Benneke and his colleagues used models to determine that the height was the perfect pressure and temperature for water to survive.

“The only plausible explanation is that these are liquid water clouds, very similar to what we have on Earth,” Benneke said.

As the clouds fill with water droplets, they most likely create rainfall. But that rain would never touch the ground. Instead, it would fall until temperatures and pressures caused it to evaporate once again, the researchers said. Benneke compared rainfall on K2-18b to terrestrial virga, which occurs when high temperatures and pressures cause rain to evaporate before it reaches the ground.

Finding a similar weather pattern on an exoplanet is an intriguing prospect to Benneke.

“[K2-18b] is the coldest planet with [atmospheric] detection, the smallest planet, the least-massive planet,” he said. “To me, it’s the most exciting one.”

A common mystery

Although K2-18b has the right conditions for Earth-like clouds to form, that doesn’t make the planet itself Earth-like. Instead, it is classified as a sub-Neptune, a gas giant without a surface. NASA’s Kepler spacecraft determined that sub-Neptunes are likely the most common type of exoplanets in the Milky Way, making up more than three-fourths of the planetary population.

Nonetheless, astronomers are having a difficult time understanding the relatively small gas giants, and that’s one reason the K2-18b findings are so exciting. “We don’t quite know what’s going on with these planets,” Benneke said. “It’s probing this regime of planets that we have a very poor understanding of right now.”

Sub-Neptunes have masses that fall somewhere between Earth and Neptune, and there’s no analogue in the solar system. Understanding worlds like K2-18b can help improve scientists’ knowledge of how planets grow and evolve. “If you want to understand planets as a whole, the diversity of planets, it’s very critical that you understand the most common ones,” Benneke said.

Source: Space.com

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.