Organic compounds called thiophenes are found on Earth in coal, crude oil and oddly enough, in white truffles, the mushroom beloved by epicureans and wild pigs.

Source: Phys.org

Thiophenes were also recently discovered on Mars, and Washington State University astrobiologist Dirk Schulze-Makuch thinks their presence would be consistent with the presence of early life on Mars.

Schulze-Makuch and Jacob Heinz with the Technische Universität in Berlin explore some of the possible pathways for thiophenes’ origins on the red planet in a new paper published in the journal Astrobiology. Their work suggests that a biological process, most likely involving bacteria rather than a truffle though, may have played a role in the organic compound’s existence in the Martian soil.

“We identified several biological pathways for thiophenes that seem more likely than chemical ones, but we still need proof,” Dirk Schulze-Makuch said. “If you find thiophenes on Earth, then you would think they are biological, but on Mars, of course, the bar to prove that has to be quite a bit higher.”

Thiophene molecules have four carbon atoms and a sulfur atom arranged in a ring, and both carbon and sulfur, are bio-essential elements. Yet Schulze-Makuch and Heinz could not exclude non-biological processes leading to the existence of these compounds on Mars.

Meteor impacts provide one possible abiotic explanation. Thiophenes can also be created through thermochemical sulfate reduction, a process that involves a set of compounds being heated to 248 degrees Fahrenheit (120 degrees Celsius) or more.

In the biological scenario, bacteria, which may have existed more than three billion years ago when Mars was warmer and wetter, could have facilitated a sulfate reduction process that results in thiophenes. There are also other pathways where the thiophenes themselves are broken down by bacteria.

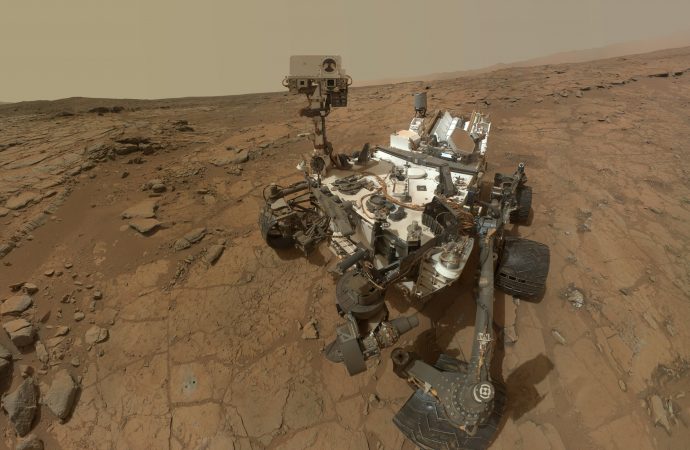

While the Curiosity Rover has provided many clues, it uses techniques that break larger molecules up into components, so scientists can only look at the resulting fragments.

Further evidence should come from the next rover, the Rosalind Franklin, which is expected to launch in July 2020. It will be carrying a Mars Organic Molecule Analyzer, or MOMA, which uses a less destructive analyzing method that will allow for the collection of larger molecules.

Schulze-Makuch and Heinz recommend using the data collected by the next rover to look at carbon and sulfur isotopes. Isotopes are variations of the chemical elements that have different numbers of neutrons than the typical form, resulting in differences in mass.

“Organisms are ‘lazy’. They would rather use the light isotope variations of the element because it costs them less energy,” he said.

Organisms alter the ratios of heavy and light isotopes in the compounds they produce that are substantially different from the ratios found in their building blocks, which Schulze-Makuch calls “a telltale signal for life.”

Yet even if the next rover returns this isotopic evidence, it may still not be enough to prove definitively that there is, or once was, life on Mars.

“As Carl Sagan said ‘extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,'” Schulze-Makuch said. “I think the proof will really require that we actually send people there, and an astronaut looks through a microscope and sees a moving microbe.”

Source: Phys.org

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.