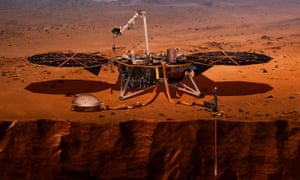

InSight, which touched down in 2018, proves beyond doubt that Mars is seismically active

Source: The Guardian

The latest robot to land on Mars has felt the ground shake beneath its feet, whirlwinds tear across the surface and sudden blasts of air shoot past like “atmospheric tsunamis”.

The measurements are the first to be released from Nasa’s InSight lander, which touched down in the barren expanse of Elysium Planitia in November 2018 on a mission to investigate the planet’s interior.

Armed with a seismometer sensitive enough to detect vibrations smaller than the width of an atom, InSight recorded 174 marsquakes in its first 10 months, proving beyond doubt that the dust-strewn planet is seismically active. That number has since risen to 450 or so.

Some of the strongest marsquakes have a magnitude of three to four and appear to come from Cerberus Fossae, a region of faults and lava flows 1,000 miles (1,600km) east of the lander. Because the pressure waves bounce around inside the planet, they can reveal crucial details about its internal structure.

“We’ve finally, for the first time, established that Mars is a seismically active planet,” said Bruce Banerdt, principal investigator on the InSight mission at Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. The tremors show that Mars is less active than Earth but more active than the moon, where seismic activity was recorded during the Apollo programme.

Mission scientists are analysing the marsquakes to see what information they hold about the crust and deeper layers of Mars. The scattering of the waves shows that the upper crust has been broken up, either by geological activity or meteorite impacts, and that this layer changes six miles down.

Some of the marsquakes are of uncertain origin. If they are not unleashed by geological faults, the tremors may come from asteroid impacts or volcanic activity. The latter raises the prospect of there being pockets of magma on Mars, and with them a potential source of warmth for any microbes that may lurk beneath the surface.

So far, the lander has failed to record any of the strongest marsquakes that scientists had predicted. These would penetrate deep inside the planet and so provide the best chance to learn about its structure. “If we don’t get those quakes, it will be a disappointment,” said Banerdt.

The measurements from InSight’s first 10 months on Mars appear in a suite of papers published in Nature Geoscience and Nature Communications. They include recordings from the onboard weather station, which sensed more than 10,000 whirlwinds in the lander’s vicinity. Some are believed to have reached a mile into the sky.

Aymeric Spiga, an atmospheric scientist at Sorbonne University in Paris, said the afternoon sun warmed the ground and drove turbulence that whipped up the whirlwinds. The air is so thin that they pose little danger, but they do help by blowing dust off the solar panels used to power the lander.

Beyond the whirlwinds, whose meandering tracks were captured by InSight’s cameras, the lander detected giant oscillations known as gravity waves in the Martian atmosphere. These can be caused by winds slamming into mountains, sending powerful uprushes skywards.

Other strange effects were spotted in the evening, such as sudden blasts of air racing past the lander. These are likely Martian versions of the katabatic winds that batter Antarctica. When the sun goes down, the air cools fast and surges down mountainsides and out on to nearby plains. “It’s a kind of atmospheric tsunami,” said Spiga.

Further measurements show that the magnetic field at the landing site was 10 times stronger than expected. The field comes from ancient rocks that formed and became magnetised when Mars still had a global magnetic field, billions of years ago.

An ongoing glitch is affecting a spear-like heat probe designed to burrow five metres into the Martian soil to measure heat rising through the planet. The probe was deployed a year ago but became stuck after burrowing less than half a metre. Mission scientists plan to place the lander’s robotic arm on the probe to help it on its way.

John Bridges, a professor of planetary sciences at Leicester University, who is not involved in the mission, said the number and magnitude of recorded marsquakes compared well with predictions made decades ago from observations of faults and rifts around the large volcanic regions on Mars.

“Some of the lava flows near the InSight lander have been dated at a few millions of years old – amazingly young when we consider the small size of Mars relative to the Earth. The growing seismic record from InSight will be essential in order to work out if Mars is still undergoing deep-mantle convection and even volcanism,” he said.

Source: The Guardian

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.