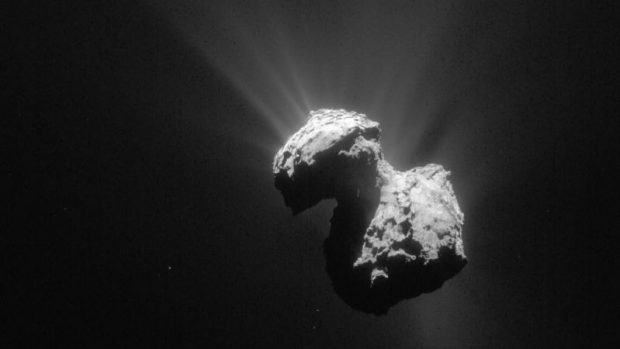

A review of data taken over the course of the two-year Rosetta mission shows that comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko was sometimes reddish in appearance, while at other times it assumed a bluish hue. Sounds weird, but scientists have come up with a sensible explanation that doesn’t involve aliens with paint guns.

Source: Gizmodo

New research published in Nature shows that comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko changes colour depending on its orbital location. The comet’s rocky nucleus became bluer when it approached the Sun but then turned red as it travelled away. At the same time, the comet’s coma – the surrounding bubble of gas and dust – performed the opposite trick, appearing red near the Sun and blue when far away.

The authors of the new study, led by Gianrico Filacchione from INAF-IAPS, Institute for Space Astrophysics and Planetology in Italy, have linked this spectral variability to the amount of water ice on the comet’s surface and in the area immediately around it.

The European Space Agency’s Rosetta probe took countless measurements of comet 67P during the course of the two-year mission, which started in July 2014 and ended in late September 2016. Among the data collected were nearly 4,000 images taken by the Visible and Infrared Thermal Imaging Spectrometer (VIRTIS) instrument, which revealed the comet’s chameleon-like behaviour.

Comet 67P, whose elliptical orbit takes it past Jupiter and then closer the Sun every 6.4 years, was still far from the Sun when Rosetta began its duties. Observations from that initial time period revealed a dusty surface with scant traces of visible ice. Images taken by the VIRTIS instrument revealed a distinctly reddish nucleus.

Eventually, however, the comet got closer to the Sun and ventured past the solar system’s frost line – a boundary within which exposed water ice undergoes a chemical process called sublimation. This is when a substance goes directly from a solid to a gas, does not pass go, and does not collect $200. Past the frost line, VIRTIS revealed a visibly less red comet, with new hints of blue.

The authors say the sublimating water ice displaced the tiny grains of dust on the comet’s surface, causing “the exposure of more pristine and bluish icy layers on the surface,” as they wrote in the study. In terms of what’s producing the colours, the red is from organic molecules rich in carbon and the blue is from frozen water ice that’s rich in magnesium silicate, according to the research.

These colour flips, however, were switched around in the coma. When outside of the frost line, the coma was blue, but when steering close to the Sun, it turned red. The reason, say the authors, is that ice in the dust grains within the coma remained in a frozen state when the comet was far from the Sun – hence the blue colour. But when the ice sublimated, the process highlighted the dehydrated – and very red – dust grains. Beyond the frost line, the situation reversed, and the coma once again turned blue.

It’s the circle of life, in a Lion King sort of way, or an “orbital water-ice cycle” as the authors describe it. The new study shows how comet 67P’s nucleus and coma evolve during an orbit, and how this comet and probably others like it undergo seasonal changes.

These sorts of observations could only have been possible with a space probe. The only thing better would be a sample return mission, which would allow researchers to analyse some of that precious carbon-rich dust up close. By studying these organic compounds, scientists could improve their understanding of their origin and how they may have contributed to life on Earth.

Source: Gizmodo

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.