Yarrabubba Crater was blasted out by an asteroid or comet about 2.23 billion years ago.

Source: Space.com

Scientists have identified the oldest known impact crater on Earth — and the ancient structure could tell us how our planet emerged from a long-ago frozen phase.

Yarrabubba Crater, a 43-mile-wide (70 kilometers) geological feature in Western Australia, is 2.229 billion years old, plus or minus 5 million years, a new study reports. That’s about half the age of Earth itself and 200 million years older than the previous record holder, the 190-mile-wide (300 km) Vredefort Dome in South Africa.

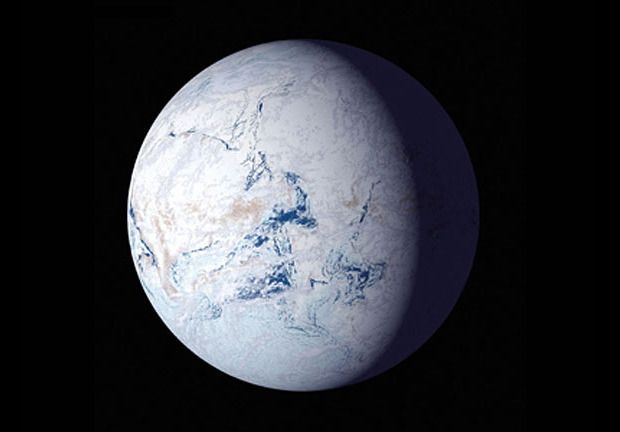

Intriguingly, the Yarrabubba impact appears to have occurred just as our planet started coming out of a “Snowball Earth” period, when much of the planet was covered by ice. And that may not be a coincidence, study team members said.

“The age of the Yarrabubba impact matches the demise of a series of ancient glaciations,” co-author Nicholas Timms, an associate professor in the School of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Curtin University in Western Australia, said in a statement.

“After the impact, glacial deposits are absent in the rock record for 400 million years,” Timms added. “This twist of fate suggests that the large meteorite impact may have influenced global climate.”

Ancient craters such as Yarrabubba are difficult to find on our active Earth. Many get buried when crustal plates dive beneath each other, and most others are worn away by wind and water over the eons.

Indeed, “Yarrabubba no longer even looks like a crater,” study lead author Timmons Erickson, from NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston and Curtin University’s School of Earth and Planetary Sciences, told Space.com.

But a different team of scientists — led by Francis Macdonald, now a geology professor at the University of California Santa Barbara — recognized Yarrabubba as such back in 2003, thanks to measurements of magnetic anomalies in the area and the presence of rocks shocked by an impact.

It was clear that the Yarrabubba strike occurred long ago, but its exact age had remained elusive until now. In the new study, which was published online today (Jan. 21) in the journal Nature Communications, Erickson and his colleagues analyzed tiny pieces of Yarrabubba’s shocked rock.

Specifically, the researchers studied grains of monazite and zircon that were recrystallized by the impact, measuring the amounts of uranium, thorium and lead contained in each. Monazite and zircon readily take up uranium but not lead when they crystallize, and uranium and thorium radioactively decay into lead at known rates. So, these measurements told the team how long ago that recrystallization occurred.

Yarrabubba’s age is intriguing, because a lot was going on 2.229 billion years ago. For example, photosynthesizing cyanobacteria had just started pumping large amounts of oxygen into Earth’s atmosphere, initiating a dramatic process known as the Great Oxidation Event.

The planet also came out of a deep freeze — one of multiple snowball phases Earth has experienced during its 4.5-billion-year history — around the time of the Yarrabubba impact. To see if these two events might possibly have been connected, Erickson and his colleagues performed computer simulations of the Yarrabubba strike.

This is not a crazy thought; after all, the catastrophic, dinosaur-killing impact of 66 million years ago is thought to have wrought much of its destruction via rapid and dramatic climate change.

The researchers’ models slammed a 4.3-mile-wide object (7 km) into a frigid Western Australian landscape, one covered by an ice sheet that ranged from 1.2 miles to 3.1 miles (2 to 5 km) thick in various runs. They found that such a strike would instantly vaporize between 23 cubic miles and 58 cubic miles (95 to 240 cubic km) of ice and cause up to 1,300 cubic miles (5,400 cubic km) of total melting.

This suggests that between 200 trillion lbs. and 440 trillion lbs. (90 trillion to 200 trillion kilograms) of water vapor, a potent greenhouse gas, were blasted into Earth’s upper atmosphere immediately after the Yarrabubba impact.

Not enough is known about the ancient Earth’s atmospheric structure and composition to confidently model how this injection of water vapor would have affected climate, Erickson and his colleagues stressed.

“Nevertheless, considering that Earth’s atmosphere at the time of impact contained only a fraction of the current level of oxygen, a possibility remains that the climatic forcing effects of H2O vapor released instantaneously into the atmosphere through a Yarrabubba-sized impact may have been globally significant,” they wrote in the new study.

Discovering and dating additional ancient craters could help answer such questions. And there should be more such features out there to find, Erickson said. After all, Earth got pummeled by far more impactors in its youth than it does now. (By the way, the new study does not present the evidence of the oldest known impact. Researchers have found ejecta — bits of rock blasted out by asteroid or comet strikes — that are up to 3.4 billion years old. But their associated craters have not been identified.)

And geologists could conceivably get windows onto an even deeper past than that afforded by Yarrabubba, Erickson said. Researchers probably can’t untangle the complicated history of the oldest known rocks on Earth, which are 4 billion years old, he said, but they might have some luck with the ancient nuclei known as cratons.

“They stretch back to 2.5 to 3.5 billion years old,” Erickson said. “I think, theoretically, it’s possible to find impact craters in that age range.”

Source: Space.com

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.