NASA has carried out its first all-female spacewalk, but hints of outdated thinking about women in space remain.

Source: The Atlantic

Two astronauts spent their workday floating in outer space, their spacesuits tethered to the International Space Station so they didn’t drift away.

And for the first time in history, they were both women.

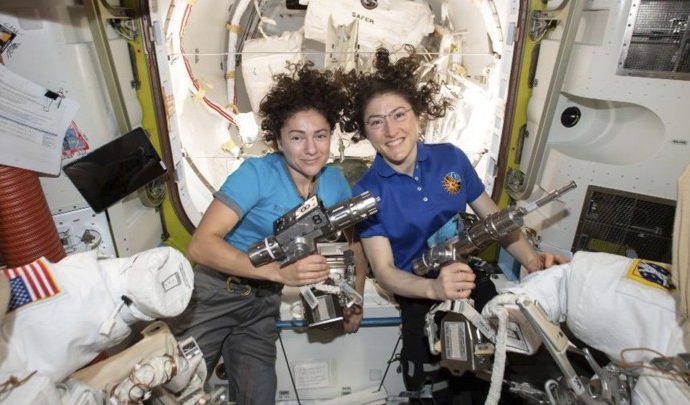

Christina Koch and Jessica Meir began a five-and-a-half-hour spacewalk this morning to replace a battery component on the station’s exterior. The device, which is used to charge the solar-powered batteries that power the station, failed last weekend.

The spacewalk itself was pretty uneventful—spacewalks, as I recently learned while watching seven hours of one, are essentially home-improvement projects for humankind’s home in space, complete with drills, bolts, and sore muscles. The excitement around the event was about the spacewalkers themselves, the 14th and 15th women to spacewalk since the first woman, the Soviet cosmonaut Svetlana Savitskaya, did it in 1984. Anticipation was especially high after an earlier attempt at an all-female spacewalk in March. That lineup was scrapped at the last minute after two female astronauts found that the ISS didn’t have enough spacesuits in the size they needed. This time, NASA officials said, astronauts had the right stuff, sartorially speaking.

NASA astronauts, working in pairs, have carried out more than 200 spacewalks in the past two decades. At a press conference at the agency’s headquarters in Washington, D.C., before the historic spacewalk, a reporter asked officials why it had taken this long to conduct one featuring two women.

“There are some physical reasons that make it harder sometimes for women to do spacewalks,” said Ken Bowersox, the acting associate administrator for NASA’s division of human exploration and operations. “It’s a little bit like playing in the NBA. I’m too short to play in the NBA, and sometimes physical characteristics make a difference in certain activities, and spacewalks are one of those areas where just how your body is built in shape, it makes a difference in how well you can work the suit.”

Bowersox, a former astronaut who flew on the Space Shuttle five times and spent more than five months on the ISS, pointed to the fact that women are statistically smaller in stature than men. “There have been a lot of spacewalks where very tall men were the ones that were able to do the jobs because they were able to reach in and do things a little bit more easily, get into crevices and things like that,” he said.

Bowersox went on to say that women astronauts have worked around these constraints. “But we’ve also brought women into the crews because of their brains,” he said. “They come in, they bring different skills, they think of things differently. And by using their brains, they can overcome a lot of those physical challenges.”

The remarks were startling. They bore the echoes of early discussions about women’s fitness for spaceflight—for any work once considered the sole domain of men, really—that focused on women’s physical and biological attributes, and, often, the reasons those attributes disqualified them from the job. Bowersox’s comments glossed over factors that might better explain why it’s taken 20 years for two women to spacewalk at the same time—none of which has to do with women’s bodies.

Today’s astronauts wear spacesuits that were made in the 1970s. The earliest designs called for suits to come in a variety of sizes, from extra small to extra large, but budget cuts eventually trimmed down the options. Most astronauts fit into the mediums and larges, but not all, and the sizing constraints actually influenced who got to live on the ISS and who didn’t. Every crew member must be able to spacewalk, and that depends on fitting in a suit. “As a woman, doing spacewalks is more challenging mostly because the suits are sized bigger than the average female,” Peggy Whitson, a retired NASA astronaut who helped build the ISS and conducted 10 spacewalks, once said.

But this is a limitation of the design of spacesuits, not women’s bodies. “Absolute ugh,” Ellen Stofan, a former NASA chief scientist and the current director of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, tweeted when she saw Bowersox’s remarks on social media. “No physical reasons. Not small enough spacesuits. Equipment problems held women back—and the men who made decisions about that equipment.” This argument came up in the spring, when Koch and Anne McClain both needed medium-size spacesuits. The ISS had two on board but only one was properly configured for spacewalking, and the other would take half a day to prepare. As far as the public was aware, NASA had never had a problem dressing two men for spacewalks. McClain ended up sitting out the spacewalk, and Nick Hague, a male colleague, took her spot.

Bowersox also said he hopes that all-women spacewalks will become routine. He said that while NASA once spent more money on developing spacesuits for men because most astronauts were men, the agency is working to adjust designs so that they fit more people comfortably—“smaller people, not just women, but smaller men.”

There are more female astronauts today than ever before, and two of them just added another chapter to the history books. Hearing a NASA official ascribe the lack of female-led spacewalks, in part, to differences between men and women—rather than to the constraints of the spacesuits NASA makes them wear—felt like traveling back in time to the 1960s.

Jim Bridenstine, the NASA administrator, seated next to Bowersox, chimed in to say that women are sometimes better suited for spaceflight than men are. “Cranial pressure for women seems to be less than that of men when you’re in a microgravity environment for long periods of time,” he said. Bridenstine was referring to a side effect of spaceflight that occurs when bodily fluids, free from the pull of gravity, put pressure on the optic nerve. The phenomenon can lead to long-term vision changes.

The American astronaut corps has come a long way since its early days as a boys’ club—specifically a white boys’ club. Its latest class of recruits, for example, includes five men and five women, and five recruits are people of color. (On the ground, NASA employs more women and people of color than ever before, though its workforce remains mostly male and white.) The agency no longer requires astronaut candidates to provide their gender and ethnicity on their application, and during the last round, 24 percent of applicants decided to leave those fields blank, according to a spokesperson.

But there still aren’t enough women in the astronaut corps to regularly fill out spacewalking teams—let alone space-station crews—or, sometimes, the right uniforms to accommodate them. NASA has tried to emphasize the importance of an inclusive astronaut corps in recent years, and officials such as Bridenstine speak often and enthusiastically about including a woman on the next mission to the moon. The story of today’s spacewalk—two talented astronauts skillfully carrying out a job they wouldn’t have been hired for half a century ago—should have been an easy showcase of these efforts. But the pre-walk press conference shrouded that accomplishment in the kind of outdated thinking that once limited women in real ways.

Source: The Atlantic

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.