A warmer Arctic in general provided the fuel for lightning-producing thunderheads to move north.

Source: National Geographic

Lightning happens all the time, but certain parts of the world get far less of it than others, including near the North Pole. Lightning requires atmospheric instability, something that’s set up when cold, parched air sits atop warmer, wetter air. At very high latitudes, that hotter, damper air tends not to show up.

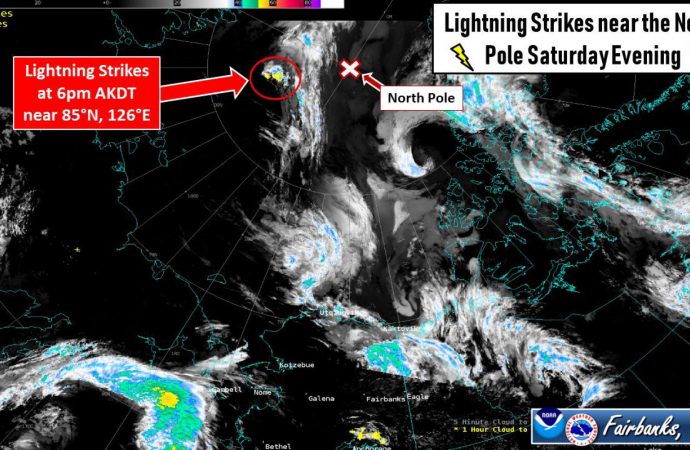

That’s why it took scientists by surprise when dozens of lightning strikes were detected within 300 nautical miles of the North Pole this past weekend. In fact, it was so unusual that it was highlighted on Twitter by the National Weather Service’s office in Fairbanks, Alaska. A bulletin of theirs said this was “one of the furthest north lightning strikes in Alaska forecaster memory.”

Although plenty of factors needed to come together to produce the lightshow, the specter of climate change lingers over this meteorological mystery. It is possible that a freakishly warm Arctic, a staggering lack of sea ice, and even possibly smoke from unprecedented wildfires within the Arctic Circle, among other things, contributed to this lightning’s unexpected appearance near the top of the world.

“It has been an extraordinary year and an extraordinary summer in the far north,” says Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Weird things are happening in the Arctic, and quirky lightning is yet another peculiarity to add to the growing list.

Bolts from the blue

The lightning was detected by Vaisala’s GLD360 network, which uses a worldwide distribution of GPS-synchronized radio receivers that pick up on the powerful radio bursts lightning discharges unleash. Individual sensors can detect such radio bursts 6,000 miles away from their sources, which allows the network to spot lightning anywhere on Earth, including the remotest Arctic.

Ryan Said, a research scientist with Vaisala and the inventor of the GLD360 system, explained that lightning had been reported within 300 nautical miles of the North Pole before. Between 2012 and 2017, there was no more than one single day each summer where lightning was seen within this range, and sometimes none was detected. In those years, the most discharges recorded in that area in a single day was six.

This weekend’s storm was unusual due to the high number of lightning discharges detected in a short span of time. There were 48 individual discharges within 300 nautical miles of the pole, with more than 1,000 detected within 600 nautical miles of the pole.

Lightning in the Arctic Circle as a whole isn’t that unusual, and portions of northern Alaska and Siberia see some lightning almost every summer. But, said Swain, once you hit the coast of the Arctic Ocean and head north, you tend not to get strong updrafts nor enough atmospheric instability to produce lightning-capable clouds.

Lightning also prefers tall clouds that allow electrically charged water and ice particles to have room to separate from each other, but near the North Pole, that’s problematic. There, the tropopause—the stable layer that forms the lid on the active weather layer in the atmosphere—is about half as high than it is near the equator. That means clouds would find it difficult to reach the heights necessary to produce that all-important charge separation, Swain said.

With that in mind, scientists were initially and understandably skeptical about this lightning detection, Said said. So much lightning really shouldn’t be turning up that far north.

Cooking up a storm

Rick Thoman, an Alaska climate specialist at the International Arctic Research Center, speculates as to how the lightning was forged. A mass of hot, moist air moving north from Siberia was lifted to higher altitudes, above the water and ice-cooled air in the lowest levels of the atmosphere. That created a very intense lapse rate in the atmosphere, where air temperature decreased very rapidly with altitude.

That strong temperature gradient, along with the high moisture content of the air mass, helped to generate billowing clouds able to generate lightning. Clearly, this doesn’t happen all the time, so what was different this year?

Historically, even during the summer, Arctic waters were frozen solid, said Swain. That’s increasingly no longer the case, and this summer, portions of the ocean basin have no ice at all.

“This is a year of extraordinary warmth and lack of sea ice throughout the Arctic,” he says, and those unusual preconditions may have in part set the stage for lightning.

Waters along the Arctic Ocean coastline are extraordinarily warm right now because they have been sitting in the summer sunlight for several months without any reflective sea ice to shield them. Along with the warmer Arctic in general, that mechanism boosted the heat and humidity of the air in the region.

In the past such a plume of warm, moist air migrating north from Siberia would have encountered ice, quickly cooled down and perhaps petered out. Today’s hotter, ice-free ocean may have allowed the plume to journey far closer to the North Pole.

At the same time, the intense wildfires raging throughout Siberia may have given the warm air mass an injection of smoke. Those particles help clouds form, so it’s possible, said Swain, they may also have played a role in producing lightning-capable clouds.

In addition, a warming polar environment will expand the weather-containing troposphere, Thoman said. That may allow more room for those towering, ice and water droplet-containing, lightning-capable clouds to develop.

A shocking future

Remote observations of lightning at such high latitudes only go back a few decades, but its appearance near the North Pole seems to be “extremely rare,” says Swain. More research needs to be conducted to confirm the triggering mechanisms, but it has some “circumstantial links to the unusual state of the Arctic this summer, which is itself linked to climate change,” he says.

Although it will still remain relatively rare, near-polar lightning should become more common as the world continues to cook.

At the same time, our remote sensing and lightning detecting capabilities are improving. That, says Marshall Shepherd, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Georgia, means that we will likely get more of these “shocking” moments going forward.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.