For a few decades now, the leading edge of science and especially astronomy has been at least partially dedicated to the search for one of the most fundamental philosophical questions we have — are we alone in the universe?

Source: Geek.com

The search has gone on long enough that many wonder why we haven’t found anything or anyone yet. And to be clear —we have found *A TON*, just not any aliens. So, what gives?

The astute among you may be calling to mind the Fermi Paradox, a thought experiment that wonders why we haven’t met anyone if the universe is as insanely huge as it appears to be. Though it’s worth taking a step back and recognizing that the infamous paradox likely isn’t — the reality of the matter is that if we were trying to find someone like us sewn between the stars, we wouldn’t turn up anything.

Our radio signals are too weak and our telescopes just aren’t sensitive enough. Much as it may boggle the mind that Hubble can spy the oldest galaxies in the universe but not the lunar landers, so too are we effectively blind in the great cosmic dark.

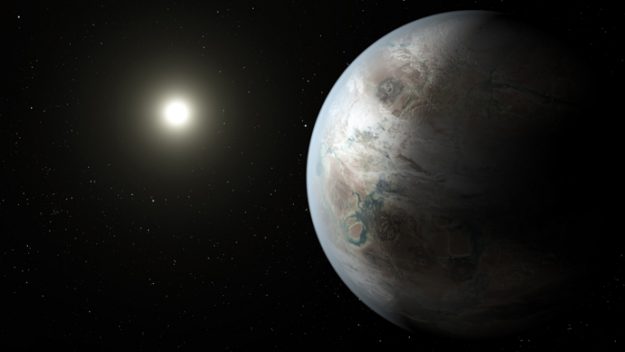

That won’t remain so forever, though. The now-defunct Kepler Space Telescope (RIP) found hundreds of extrasolar worlds, but observed few with the precision needed to understand what was in its atmosphere. And that’s actually one of the next big steps in the search for extraterrestrial life.

Radio signals, especially the omni-direction kind we’ve been blasting out for almost a century are just vague whispers in the cosmos. A much better route, at least for now, is honing in on the nearby planets that may have atmospheres amenable for life. Right now, we know where a lot of exoplanets are, and we know whether they fit into their parent’s habitable zone. But the difference between Venus, Earth, and Mars is largely attributable to their varying atmospheric conditions.

Like the tale of Goldilocks, Venus is far too thick, so much so that it would choke out just about any life and blanket the nascent organisms with sulfuric acid before they could get going. Mars, far too thin. And without a large biosphere like our own, incapable of replenishing what it sheds. Earth, on the other hand, is just right, but with a catch — our atmosphere is anything but natural.

Oxygen, one of the most reactive (i.e. useful) chemicals on the periodic table, doesn’t just chill on Earth. It reacts. Binding to rocks, rusting metal, etc. In fact, where it not for the insane amount of plant and algal life on Earth, we couldn’t maintain the concentrations of oxygen we’d have for long. Eventually, it’d just all go back into the ground.

That is why understanding what’s in a planet’s atmosphere is so critical though. It yields far, far more insight than you’d expect. If we also detect organic molecules like methane and even water vapor, then we can start confidently saying we have a possible garden world.

The tech to make those assessments is also more or less here, and we’re waiting for the deployment of the next generation of mechanical planet-hunters.

NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is among the first such projects, and will be searching for worlds within 300 light-years of our own. Within that range, it will be able to detect at least some of the atmospheric spectra for exoplanets. Still, with many thousands of stars in its search area, it will still be a preliminary search.

Other near-term projects include the mighty (but oft-delayed) James Webb Space Telescope, now pushed back until 2020 as well as the 30 meter ground-based telescope planned in Hawaii. With these, we’ll be able to more directly image other planets, and discern just what they got cookin’.

Approaching the search for life from the other direction are projects like the Square Kilometer Array a truly Herculean undertaking to create a telescope network that can process data at an astounding speed. Because it’s an array, it’s been built out in stages, with Phase 2 still in early planning. Still, the core system is in use now, and if completed, would yield more data than the whole of the internet in 2013. Even with beasts like these, though, signs of life may be fleeting and rare.

Many scientists are optimistic, in large part because life transitioned to producing oxygen not too long after life began, that many planets may have such biospheres. But even if they did, we are separated by hundreds of millions of evolution from that slice of our own history. It may be turn out to be that the path to intelligence is far harder than we suppose. And it may be that the universe truly is a lonely, desolate cosmos. Just don’t count life out yet. As we know, it certainly has a tendency to find a way.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.