Experts say planet could offer new insights into how solar system formed

A British-built spacecraft fitted with Star Trek-style “impulse engines” is on its way to Mercury, the planet closest to the sun.

BepiColombo blasted into space from the European space port at Kourou, French Guiana, at about 2.45am UK time on Saturday. It was carried on top of an Ariane 5, the European Space Agency’s (ESA’s) most powerful rocket.

After a tense countdown in French, the rocket rose slowly above a ball of orange flame and thundered into the sky before disappearing into cloud.

Experts say BepiColombo could not only shed light on the mysteries of our neighbourhood’s smallest planet, but also offer new insights into how the solar system formed and even provide vital clues as to whether planets found orbiting other stars – so-called exoplanets – could be habitable.

“If we want to understand our Earth and how life can [begin] on Earth and maybe on other planets, we have to understand our solar system,” said Joe Zender, the deputy project scientist for BepiColombo.

Much progress has been made in the matter, Zender said, but there is a snag. “There is one problem really, which is Mercury. Mercury doesn’t fit.”

Among the puzzles is the planet’s surprisingly high density and that it is thought to have a core that is at least partly molten. With some exoplanets orbiting very close to stars cooler than our own, finding out more about the first rock from our sun has become a pressing matter.

The BepiColombo mission is a €1.6bn (£1.4bn) joint venture between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japanese space agency, Jaxa.

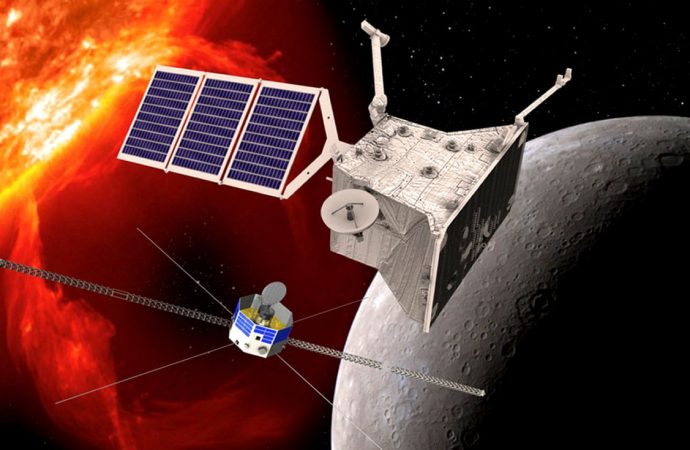

The mission has a hefty price tag, but is arguably something of a bargain because BepiColombo involves not one orbiter but two. Once the spacecraft has been delivered into orbit around Mercury by the ESA-built Mercury transfer module, it will split to lose a protective sunshield and release the Mercury magnetospheric orbiter, built by Jaxa, and the Mercury planetary orbiter, built by ESA.

Mercury is only 58m km from the sun, but it has rarely been in the spotlight. Just wo previous missions have examined the planet’s properties – Nasa’s Mariner 10 probe, launched in 1973, and the more recent Messenger mission, which launched in 2004.

The latest endeavour takes its named from the late Giuseppe “Bepi” Colombo, a professor at the University of Padua who was a key figure in devising Mariner 10’s Mercury flybys.

Both previous missions threw up intriguing results, including that Mercury has a magnetic field. This was a surprise given its leisurely pace of rotation – it takes 59 Earth days to spin on its axis – and the idea that because of its small size, the planet’s core would have cooled and become solid, precluding the existence of a magnetic field. Mercury’s magnetic field is also offset by 20% of the planet’s radius, meaning certain features at the south pole are different to those at the north.

Mercury was also found to have an exosphere, a very thin layer above the surface composed of atoms and molecules that have come from the crust and solar wind.

Before BepiColombo can examine such phenomena, however, it must negotiate two major hurdles.

“The heat is really severe, 450C on one side, but don’t forget the other side is -180C,” said Dr Suzanne Imber, of the University of Leicester, who is a co-investigator on MIXS – one of the Mercury Planetary Orbiter’s 11 instruments – and also worked on Messenger. Our spacecraft “is going from one to the other over a few tens of minutes … our instruments have to operate around room temperature.”

The Japanese orbiter will spin 15 times a minute to avoid being toasted, like a kebab on a barbecue, while the European orbiter will be wrapped in a special multi-layer blanket and have a radiator for protection.

Getting to Mercury is also a head-scratcher. “Mercury is a small body close to the sun, so you could fly straight towards Mercury and get there in a few months, but you can’t stop because the sun’s gravity sucks you in,” said Imber.

The answer is to arrive slowly via an elegant series of laps, with the spacecraft swinging by Earth, Venus and Mercury before entering an orbit in late 2025, then splitting and beginning operations in early 2026.

“We are passing once by the Earth, twice Venus and six times Mercury,” said Zender. “We are going so close to the individual planets that we can use their gravitational forces to change our direction for the next step.”

The team also plan to examine features of Venus including its internal structure, its chemical composition and its interaction with solar radiation.

Once in orbit around Mercury, the instruments will set to work. An x-ray telescope, MIXS will help to shed light on the makeup of the planet.

“We are going to know in really incredible detail what the surface of Mercury is made of,” said Imber, adding that the team can probe deeper down, too. “When you form an impact crater what you find is that layers of material from under the surface are lifted by the impact and land on the surface,” she said.

Prof Nicolas Thomas, the co-project manager of the Bela instrument aboard the Mercury Planetary Orbiter, said he wanted to investigate the planet’s curious surface features.

“A planet will shrink as it cools and Mercury has cooled a lot. We think the planet has cooled in such a way that its radius has been reduced by 8km over its history,” he said. “There are huge great cliffs that we suspect have been created by this process where this shrinking has gone on but some bits have shrunk and other bits haven’t shrunk quite so much.”

It is a phenomenon Bela will help investigate. “What we do is that we take a seriously large, very scary powerful laser and we fire it up to about 1,000km away from the planet and then we wait for six to 10 milliseconds and we look at the reflected pulse,” said Thomas. By looking at the time it has taken for the light to return, the team can calculate the contours of the surface below, essentially mapping Mercury.

The BepiColombo mission is expected to last for two years once the orbiters are in position, but the team say it might continue for longer. Once over, the orbiters will be crashed into the planet’s surface.

Prof Emma Bunce of the University of Leicester, who heads the MIXS instrument team, said after watching the launch: “I didn’t know what to expect but it was absolutely amazing, just spectacular, the way it lit up the whole sky and the way the sound eventually reaches you. Quite emotional really.

“You think about the instrument you’ve worked for so many years on sitting on top of that rocket and you hope it’s going to be OK.”

Source: The Guardian

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.