Rice University scientists are known for exceptional research, but a new paper led by physicist Junichiro Kono makes that point most literally.

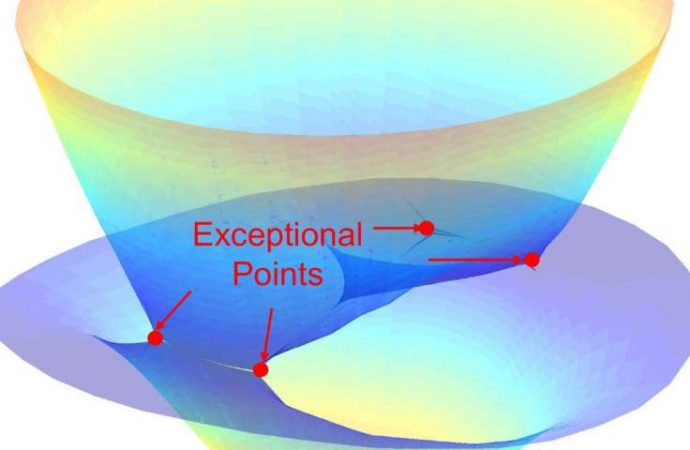

The discovery of exceptional points in a unique material created by Kono’s lab is one of several revelations in a paper that appears in Nature Photonics.

These spectral singularities are central to another phenomenon, the team’s newfound ability to continuously tune the transition between the weak and ultra-strong coupling of light and matter confined in a vacuum. That ability may give researchers the opportunity to explore novel quantum technologies like advanced information storage or one-dimensional lasers.

Kono and his colleagues have expertise in corralling photons and excitons (bound electron-hole pairs) in solids to form condensed matter in a quantum well. They reported on their ability to do so by manipulating electrons with light and a magnetic field in 2016. In the same year, they announced their ability to make highly aligned, wafer-sized films of single-walled carbon nanotubes.

In the new work, Kono and Rice postdoctoral researcher and lead author Weilu Gao combined techniques from the earlier papers and used polarized light to trigger the formation of quasiparticles known as polaritons – strongly coupled light and matter – inside the one-dimensional nanotubes in a cavity at room temperature. Because polaritons can only resonate along the aligned nanotubes’ length, they appear when incoming light is polarized in the same direction. When turned 90 degrees, the polaritons disappear progressively.

The polarization angle at which polaritons appear and disappear is known as the exceptional point, and neither Kono nor Gao considered it important until a theorist friend stepped in.

“Discovering the point was important, and surprising,” Kono said. “In our first version of the paper, we didn’t really emphasize it. But while it was under review, we showed a theorist the data and he pointed out, ‘You have this Dirac point-like feature here.’ We started to look at it more carefully, and indeed there was an exceptional point.”

Dirac points are a characteristic of graphene; they appear where the material’s conduction and valence bands connect to make it a perfect conductor of electricity. In semiconductor materials, the energetic separation between bands determines the material’s band gap.

Exceptional points have been studied in other contexts; in recent experiments, scientists showed light itself could be slowed or stopped at just such a point.

“A lot of the anomalous properties of electrons in graphene are related to the existence of this special point, called the Dirac point, or energy-zero point,” Kono said. “Graphene’s band structure is completely untraditional compared with solid semiconductors like gallium arsenide or silicon, which have conduction and valence bands that define their band gap.

“In our case, we have a kind of band gap between the upper and lower polaritons when polarized light is parallel to the films, but turning the light polarization changes everything. When you hit the exceptional point, the band gap closes and polaritons disappear.”

Kono said the work also demonstrates that the aligned nanotubes cooperate with each other. “The vacuum Rabi splitting (a measure of coupling strength between photons in the vacuum and electrons in the solid film) increases as we increase the number of nanotubes,” he said. “This is evidence that the nanotubes coherently cooperate as they interact with the cavity photons.”

Gao said the Rice experiment suggested a way might be found to create photons – elemental particles of light – from a vacuum. That could be important for quantum-level storage as a way to extract data from qubits.

“There are theoretical proposals for converting virtual photons into real photons, sometimes called Casimir photons,” Kono said. “We could have matter inside a cavity interacting with the vacuum, and when we trigger the system somehow we destroy the coupling, and suddenly photons come out. That’s an experiment we want to do, because producing photons on demand from a vacuum would be cool.”

Source: Phys.org

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.