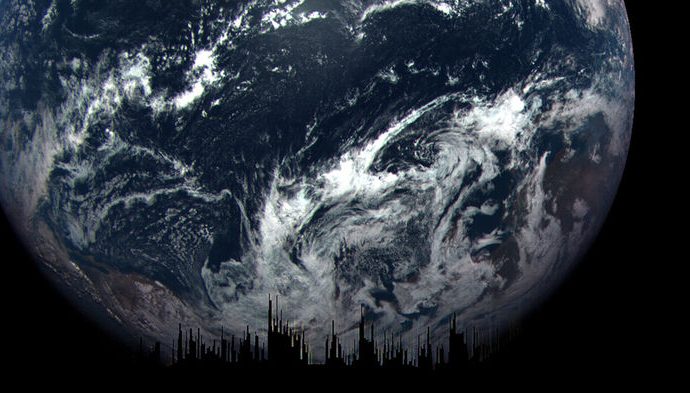

A camera onboard the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft captured this image of the Pacific Ocean, Baja California in Mexico, and parts of the southwestern United States. The dark lines are missing data caused by short exposure times

Nearly 30 years ago, the Galileo spacecraft flew past Earth on its journey to Jupiter, prompting astronomer Carl Sagan to develop a novel experiment: to look for signs of life on Earth from space. The spacecraft found high levels of methane and oxygen, suggestions that photosynthesis was occurring on Earth’s surface. Now, astronomers have repeated the experiment, this time with an asteroid-bound spacecraft that swung around Earth in late 2017. It also found Earth to be teeming with life, but with an unsettling corollary: Atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide and methane were far higher than they were during the Galileo flyby.

“It’s a challenging intellectual enterprise,” says Dante Lauretta, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona in Tucson and principal investigator of NASA’s Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security-Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx) mission. “I really tried to channel Carl Sagan.”

The main goal of OSIRIS-REx is to return samples from Bennu, an asteroid as big as the Empire State Building. But during the Earth flyby—which brought the spacecraft 22 times closer to our planet than the moon—scientists pointed its instruments toward home.

The team spotted hurricanes Maria and Jose, and its spectrographs—used to detect gases based on the absorption of specific wavelengths of light passing through the atmosphere—recorded levels of methane, oxygen, and ozone far higher than values expected from a lifeless world. That implies that biological processes were creating these compounds, the team reported last week at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas. The researchers also found that visible light was being absorbed by Earth’s landmasses, a clear sign of photosynthesis.

And in an update to Galileo’s findings, OSIRIS-REx recorded methane and carbon dioxide values that were 12% and 14% higher, respectively, than they were in 1990. That’s not surprising, Lauretta says. Twenty-seven years ago, the world contained 2 billion fewer people and far fewer sources of pollution.

These OSIRIS-REx observations are an important test of what a habitable, life-filled planet looks like from afar, says Sarah Stewart Johnson, a planetary scientist at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., who was not involved in the project. “These images and spectra underscore the dazzling possibilities for exoplanets.” But as scientists begin to comb through observations from distant worlds for signs of life, they’ll want to remember some sage advice from the Galileo team: Any measurements that suggest the existence of life must always be carefully scrutinized for other possible explanations. As they wrote, “Life is the hypothesis of last resort.”

Source: Science Magazine

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.