In a handful of medieval Bavarian farming hamlets populated mostly by blue-eyed blondes, more than a dozen women with dark hair, dark eyes, and unusual elongated skulls would have stood out.

A new DNA study suggests that these women, whose striking skulls have been unearthed from nearby grave sites, were high-ranking “treaty brides” from Romania and Bulgaria, married off to cement political alliances. Yet others are skeptical.

“This is one of the strangest things I’ve ever read,” says Israel Hershkovitz, an anthropologist at Tel Aviv University in Israel, who specializes in ancient human anatomy. “I don’t buy it.”

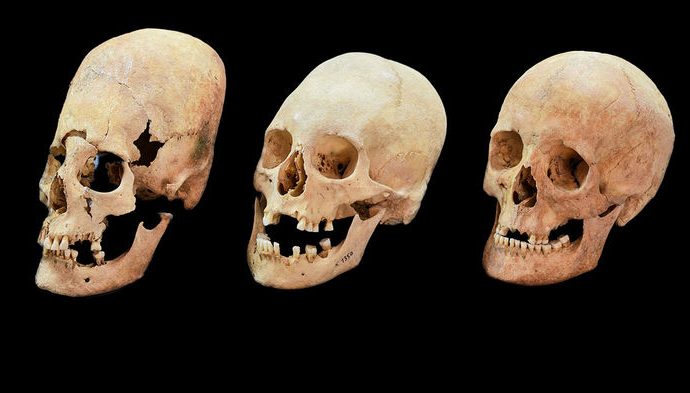

The remains, which date to about 500 C.E., are part of a pattern of elongated skulls found in gravesites across early and medieval Europe and Asia. The Bavarian skulls were unearthed alongside regularly shaped ones near six modern southern German towns along the Danube River starting in the late 1960s. Few clues exist as to their identities, or how and why the skulls were stretched. Curious about the “tower-shaped” skulls, anthropologist and population geneticist Joachim Burger, from Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany, set out to sequence their DNA.

Burger and colleagues compared the DNA from tiny bone fragments in the graves with each other and those of modern populations throughout Europe and Asia. The DNA of 10 men—and 13 women with normal skulls—most closely matched modern populations in central and northern Europe. Most had genes for blond hair and blue eyes. But DNA from the 13 women with elongated skulls told a different tale. The genetics of these women matched modern populations in southeastern Europe, specifically Bulgaria and Romania, and they had genes for darker hair and eyes, the researchers report today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

But how had they come by their elongated skulls in the first place? Burger has a theory: artificial cranial deformation. The practice—in which infants’ skulls are bound repeatedly, with their heads growing into the constricted shape—happened throughout the ancient world, notably in central Asia by the nomadic Huns. In Europe, where the earliest evidence comes from second century Romania, the practice seems to have been just as common in men as in women.

But the sex imbalance in the Bavarian graves was stark. Burger notes that because ritual deformation was such a time-intensive process, most anthropologists believe it was done only to the children of the wealthy. It could be that high-ranking southeastern European women traveled to Bavaria and married in order to shore up political alliances between the regions, he says. Whether Bavarian princesses also traveled east in return isn’t known.

Hershkovitz doesn’t dispute the genetics, but he says the story doesn’t add up. For one thing, he isn’t convinced that the skulls were deformed intentionally. Babies’ skulls can accidentally be elongated by resting on hard wooden surfaces or being strapped into carrying packs. For another, he says that when ancient tribes intermarried for political reasons, usually only one or two individuals at a time did so. It would be extremely unusual to send more than a dozen women in a single generation, Hershkovitz says.

Burger counters that no individual village in the study had more than a few women with elongated skulls. If each village were a distinct political entity with its own alliances, the political theory holds up. As for whether the skulls were deformed intentionally, Burger says it would be an extreme coincidence if all the women with elongated skulls just so happened to also have a different ancestry from the rest of the population.

Source: Science Magazine

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.