On December 17, 2017, a newspaper printed a story titled “Real U.F.O.’s? Pentagon Unit Tried to Know.” No, the headline wasn’t surrounded by text about post-baby bods and B-listers’ secret sorrows. Because it was on the front page of The New York Times.

The article describes a federally funded program that investigated reports of unidentified aerial phenomena (UAPs, the take-me-seriously acronym that includes UFOs). And within the story, the Times embedded videos of two such UAPs.

Although the article was careful not to say that unidentified meant extraterrestrial, the Department of Defense acknowledged the program, and it was easy enough for readers to draw the conclusion that these videos could show alien aircraft. The Times supplemented one of the clips with a first-hand account of a Navy pilot who was sent to investigate “mysterious aircraft” that appeared—poof!—at 80,000 feet, dropped down to 20,000, and then seemed to hover before either leaving radar range or launching straight up. Weird, right?

The discovery, and federal acknowledgement, of a UFO of non-earthly origin would be revelatory—and the Times’ scoop seemed to suggest that such a worldview-shifting scenario is at least not not-true. That the videos came courtesy of the Defense Department made it easier for readers to put faith in their validity.

“The video footage, in this case, is what captures people’s imagination and is part of what made this case more compelling,” says historian Greg Eghigian, a recent NASA and American Historical Association Fellow in Aerospace History.

But there are a few missing links in this narrative chain, links that need to be forged before anyone has enough information to accurately interpret these videos, let alone conclude they even remotely suggest anything extraterrestrial.

But wait, this story broke the news that the DOD had a secret UFO program and had released secret video! That’s huge!

Here’s what happened. About a decade ago, the Department of Defense inaugurated a UFO program, budgeted at $22 million according to the Times. It went by AATIP, for Advanced Aviation Threat Identification Program, though the Times story refers to it as the Advanced Aerospace Threat Identification Program. Its purpose was to investigate flying foreign weapon threats—ones that exist now or could be developed in the next 40 years. The product of legislation cosponsored by senators Harry Reid of Nevada and Daniel Inouye of Hawaii, the program, according to Pentagon spokesperson Audricia Harris, was primarily executed through a contract with Bigelow Aerospace—a company owned by Reid’s constituent and donor Robert Bigelow. (The wealthy businessman, who is best known for his inflatable space habitats, still owns a company called Bigelow Aerospace Advanced Space Studies, which has also researched UFO reports.)

The Pentagon program was run by Luis Elizondo, who told WIRED he took the lead position in 2010. (WIRED was unable to verify that Elizondo worked on AATIP, but Harris does confirm that he worked for the Defense Department.) The AATIP team, Elizondo says, took strange-sighting reports from pilots, as well as associated data like camera footage and radar returns, and tried to match them with known international aircraft signatures. “What we found many times was the fact that the aircraft did not belong to anybody,” Elizondo says. Sometimes, he says, the craft displayed behavior the AATIP team couldn’t explain.

Elizondo has become a kind of celebrity—in the wider world, arguably, but definitely in the UFO community. This week, those UFO researchers and enthusiasts and skeptics gathered in Fort McDowell, Arizona, for their annual International UFO Congress. And Elizondo, who had brought them closer to the capital-D Disclosure they’ve long sought, was supposed to be there. Instead, this evening at 6 pm Eastern, the Congress will show a prerecorded interview in which Elizondo will answer submitted questions from the community— “many of the questions that have gone unanswered,” according to a press release.

People have been clamoring for those answers—and Elizondo characterizes himself as being all about the answers. He says he wanted, for instance, to speak more publicly about the crafts’ non-nationality. “That fact is not something any government or institution should classify in order to keep secret from the people,” Elizondo told the Times, and the website linked to his new venture makes reference to the declassification processes the films had to undergo. The Times portrays the program as “shadowy” and possessing “excessive secrecy.”

But those are all funny things to say, because it doesn’t seem like the Pentagon ever held the program’s data or documents that close, and it doesn’t seem like the videos in that story ever were classified.

“If they were officially declassified, they would have to have been officially classified,” says Nate Jones, director of the Freedom of Information Act Project at the National Security Archive. And a classified video would likely have a marking at least at the beginning and end, even after it was okayed for public consumption. Someone—at the Times, at To The Stars—could have cut those introductory and closing seconds from the video, but why would they do that, when both groups were emphasizing the direct-from-DOD legitimacy of the videos? “It looks very strongly like these weren’t released through any proper DOD declassification channels that I’ve ever seen,” says Jones. “I’ve seen a lot of DOD declassification in response to FOIA, in response to mandatory declassification review, in response to proactive disclosure. And it doesn’t look like this.”

Here is, perhaps, why: While the details of the program weren’t widely known, Harris says that the program files the Pentagon has pored over so far—Pentagon staffers have been reviewing AATIP documentation since around the time the Times story broke—were unclassified.

Of course, there are endless quibbles to be had over classification. Elizondo, for his part, clarified to WIRED that he didn’t believe the videos themselves were ever classified: They were just stored on a classified system. Either way, though, it seems that they made their way into the world without the typical release process, which the Department of Defense requires of “all documents that are submitted for official public release.”

Information is classified, according to the National Archives, if its improper release would present a national security problem. So why would a secret program looking at aerial anomalies—“aerodynamic vehicles engaged in extreme maneuvers, with unique phenomenology,” says Harris—remain unclassified? Sounds like those UAPs weren’t so threatening after all.

Well, fine. But the videos were still part of the program, even if they weren’t classified. It even says right there: “Courtesy of US Department of Defense.”

It’s true, that’s what the December Times story says about the videos. But there are two important things to know about that credit.

First of all, Harris maintains the Pentagon isn’t the source of the videos. “The official who is authorized to release this video on behalf of DOD did not approve the release of this video,” she says. She’s adamant: “I stand firm that we did not release those videos.”

Which means that although the videos may have originated within the DOD, which Harris acknowledges they may have, there’s no public proof or Pentagon acknowledgement of their association with AATIP. Of course, perhaps the Pentagon wants it that way. In the 1950s, according to a book by investigative journalist Annie Jacobsen, the CIA’s Psychological Strategy Board concluded that the public’s potential reaction to UFOs (belief, followed by hysteria) constituted a national security threat. The ’50s were a long time ago, but we still enjoy Jell-O salad every so often, so maybe we would still be susceptible to social chaos if we were to learn about flying objects of questionable origin.

And in any case, one of the Times’ video credits has since changed. WIRED contacted the Times reporters in late December, asking them to comment on how the paper obtained the videos, and on the Defense Department’s denial that it had released them. Reporter Ralph Blumenthal replied on behalf of the three coauthors in early January, “We don’t discuss the processes by which we obtain information.” But he added, “We have official documents showing the origin of the videos and the process of review provided within the DOD before they were released.”

In mid-January, though, the Times changed the caption of the lead video in its story. Both videos still have captions stating they were “released by the Defense Department’s Advanced Aerospace Threat Identification Program.” But the page now simply says the first video is “by,” not “courtesy of,” the Department of Defense.

Journalists gonna journalism, though. Of course they’re protecting their sources. But I just so happen to know that there’s another place that has original video straight from the DOD, and they’re up-front about everything.

Ah, you must be talking about To the Stars Academy of Arts and Science.

In case other readers are not already caught up, To the Stars is a company cofounded by former Blink-182 member and longtime paranormal enthusiast Tom DeLonge. The company wants to collect data on unexplained phenomena, maybe even building out tech based on what they observe. Oh, and sell books, movies, music, and merchandise related to To the Stars’ efforts.

It also, coincidentally, now employs Luis Elizondo. Elizondo says he wanted to speak about what he says the AATIP team had seen, but he didn’t think that was possible from within the Pentagon. So he resigned in October 2017, he says, signing on with To The Stars soon thereafter (although WIRED’s FOIA request for Elizondo’s resignation letter, which was quoted in the Times, turned up no records, according to the Office of the Secretary of Defense/Joint Staff).

Also coincidentally, To the Stars launched a video-centric site on the same day the Times story came out—carrying the same two fighter-jet clips that appeared with the article. The so-called Community of Interest currently hosts one pilot report and one video interview along with the gun-camera videos—“the first official UAP footage,” the page says, “ever released by the USG.” (That’s the US government, for all you sheeple.)

While the academy’s site may make bolder claims than the Times did, that doesn’t make those claims more true. The Community of Interest page says the videos come from the Defense Department, have gone through the official declassification review process, and have been approved for public release. Further, it boasts that the academy can prove it with chain-of-custody paperwork. Its two UAP videos, together, have garnered nearly 3 million views on To The Stars’ YouTube channel, where the footage begins with on-screen text characterizing the videos as official and released.

Those chain-of-custody files aren’t public, but To The Stars did show WIRED some paperwork suggesting that the videos had gone through the Defense Office of Prepublication and Security Review (DOPSR), which is one part of the DOD’s document release procedure. DOPSR, says this guide, conducts “security and policy reviews on all documents that are submitted for official public release.” “It means that one of the steps for the review of a product has been completed,” says the Pentagon’s Harris.

But that documentation doesn’t actually clear material for release. “An approval from DOPSR does not equate to public release approval,” says Harris. To release AATIP videos by the book, someone would have had to coordinate with the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs. So the videos on the To the Stars don’t carry any more weight than the same videos published by the Times.

OK, fine. But those videos are still spooky. If we can’t trust the feds or the paperwork, we can trust our own eyes, right?

True, the videos show some weird stuff. But without a clear chain of custody, we can’t even know whether they were part of AATIP at all, or trust that they haven’t been tampered with.

And a copy of one of the much-touted videos has been online since at least 2007. UFO researcher Isaac Koi (a pseudonym under which he writes about the topic) established that the second video in the Times story, of an event in 2004, appeared online in 2007. Someone posted it on the conspiracy website Above Top Secret, and Koi delved into its origins. The first appearance he could find was on a website for a company called Vision Unlimited—a film production company. An archived 2007 version of vision-unlimited.de confirms that the footage was hosted there back then.

That archival film matches the Times video.1

After all the unclassifications and release-denials, this information shouldn’t surprise you. We’ve pretty clearly established that whatever these videos show, they don’t seem important enough for the Pentagon to get in a tizzy over. And while the fact that one of them has shown up online before doesn’t prove that they didn’t originate with the military, it does call that chain of custody into question. Without official confirmation or available documentation (and more documentation than WIRED saw), you can’t be sure what you’re viewing is unadulterated footage, and you can’t be sure who recorded it first.

To The Stars Academy acknowledges that the 2004 video has existed elsewhere; its explanation is that those incarnations were leaked versions and that theirs is original. But there’s no public proof for that statement.

It’s true, a Navy pilot named David Fravor did give an account to the Times of his 2004 experience with a UFO, and an unnamed source provided a report in September 2017 of the same events to To The Stars Academy. But squint just a little to see that there’s no definitive link between these accounts and that video. The witnesses give a description of an alleged strange event, and the video shows an encounter with a strange object. But without a time and location stamp of some sort, viewers can’t know whether the witnesses are actually describing what’s in the video. And, beyond that, there’s no definitive link between this video and AATIP.

In the end, also, there’s no way for the public to know whether, five seconds after the other film ends, the pilots don’t discover the “fleet” of crazy flyers wasn’t from Finland. Or the Air Force.

Fine, hater. What would it take to make you believe?

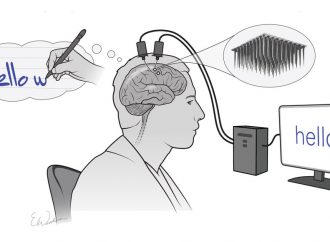

In lieu of federal nondenial, or more public paperwork, there should exist hard data—like air traffic control reports, or the radar returns Elizondo mentioned—that could help establish the videos’ actualness and officialness, as well as the UAPs’ strangeness. If someone—in an aircraft, on the ground, on a ship—sent radio waves up, and they bounced off a flying object, the timing of their return and the way those waves had changed could reveal the object’s speed, its distance, and sometimes its shape.

Will To The Stars Academy be releasing those?

Yes, Elizondo says. But how and when and where, he doesn’t know.

1 UPDATE 9:45 AM ET, 2/17/2018: This article previously included an interpretation of the text on the Nimitz video display.

Source: Wired

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.