Scientists say the unique find, believed to be 115m years old, is similar to today’s fungi

With a classic shape, gills and a sturdy stalk, it wouldn’t look out of place in a stir-fry – but in fact it’s the fossilised remains of a mushroom thought to have sprouted about 115m years ago. It is the world’s oldest known fossil mushroom, and it is remarkable that it was preserved at all.

“It is pretty astonishing,” said Sam Heads, a palaeontologist and co-author of the research from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “Mushrooms are really ephemeral in the sense that to begin with they sprout up, they grow and then usually they are gone within a few days – but they are not around for very long. Also when you consider their structure, they are very soft and fleshy and so they decay really rapidly, so the chances of one being preserved are pretty minuscule.”

While fossilised fungal filaments have previously been found dating back several hundreds of millions of years, only 10 fossil mushrooms, the fruiting body produced by some fungi, have ever been discovered – with the previous oldest dating to 99m years ago.

What’s more, all of these previously discovered fossilised mushrooms were trapped in amber. “You imagine mushrooms are growing on the forest floor, resin drops out of the trees onto the forest floor – and encapsulates a mushroom,” said Heads. “That is a much more likely scenario than the scenario that we see with this mushroom.”

The newly discovered toadstool, it would seem, met a dramatic end. Growing at the side of a river, the mushroom fell into the water, possibly as the banks collapsed in a flash flood produced by monsoon rains, and was swept into a lagoon where it ended up amid the sediment and eventually became mineralised – a scenario backed up by insect and plant fossils from the same site.

“It is really astonishing to me that the specimen made it that far in the first place without disintegrating and falling apart,” said Heads.

The mushroom, he adds, was living in a very different world to the one we inhabit, at a time when the supercontinent known as Gondwana was starting to break into the continents we have today. “At this time the earliest flowering plants had appeared and were undergoing a really huge evolutionary radiation,” said Heads. “There were dinosaurs stomping around, pterosaurs flying around in the sky – lots of different fauna,” he added.

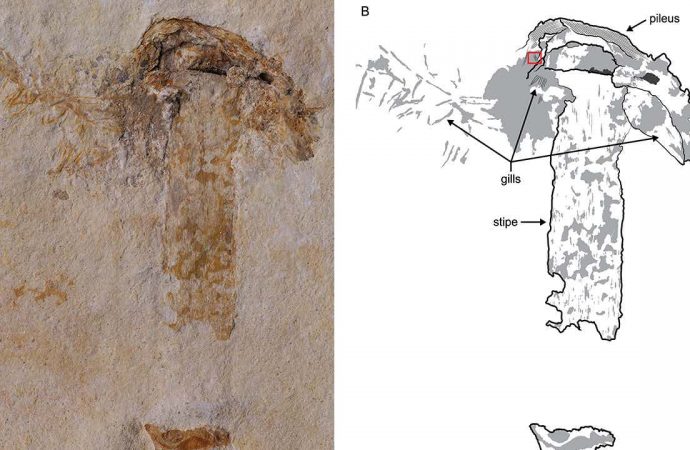

In a nod to the landmass on which it grew, the newly discovered specimen has been named Gondwanagaricites magnificus – meaning “magnificent fossil mushroom from Gondwana”. Preserved in limestone and unearthed in the Crato Formation in Brazil, the fossilised mushroom is 5cm tall and incredibly well preserved.

That, said Heads, is probably down to the environment in the lagoon which had a high salinity, little or no oxygen and nothing living on the lagoon’s floor. “Those are the sorts of conditions you need for the preservation of soft tissues,” he said.

But despite the unprecedented nature of the new discovery, the fossil nearly slipped under the radar: the specimen was among a collection of fossilised insects that had been donated to the team and only came to light when the researchers began digitising the collection.

“We actually know nothing about how it was collected, or when it was collected because it just came with this donation of material,” said Heads, adding that the discovery could prove valuable in calibrating evolutionary timescales based on so-called “molecular clock” methods.

Martin Smith, a palaeontologist from the University of Durham who was not involved in the research, said the discovery, published in the journal Plos One, is exciting.

“It’s a really cool fossil,” he said. “You look at it and you know it is a mushroom – it is not always that easy. One thing that’s true of fungi is that they tend to be very rare on [characteristics] that actually make you think, yes, this is definitely a fungus and nothing else.”

The mushroom, he adds, is very similar to those growing today – the authors note it closely resembles those in the family strophariaceae – although there is no way of knowing whether it would have been edible.

But Smith agreed that the quality of the fossil, and the fact that it was preserved at all, is remarkable. “It is almost a miracle of preservation,” he said. “We have got one fossil [mushroom] preserved in this way from the whole of the fossil record.”

Source: The Guardian

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.