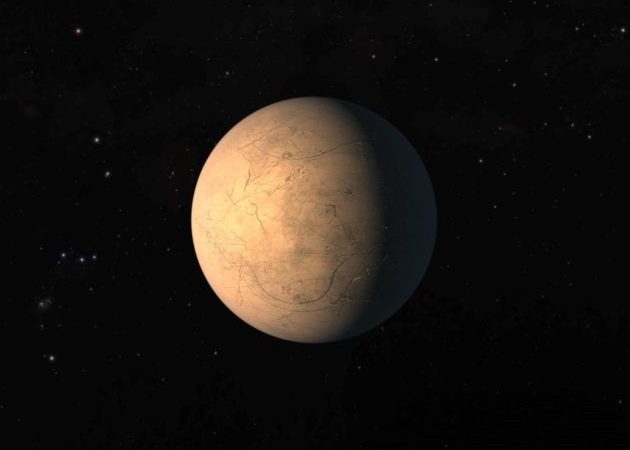

An international research team led by a University of Washington astronomer has worked out the intricate dance of seven planets circling an ultracool dwarf star known as TRAPPIST-1, nailing down the coordinates of the outermost world in the process.

The astronomers found that all seven exoplanets follow stable orbits thanks to a regular pattern of gravitational interactions, known as orbital resonance. And they determined conclusively that the seventh planet, called TRAPPIST-1h, is too cold for life – although it was could have been warmer in its ancient past.

The calculations, laid out today in the journal Nature Astronomy, will go down as another success story for the planet-hunting process.

“TRAPPIST-1h was exactly where our team predicted it to be,” the University of Washington’s Rodrigo Luger, lead author of the paper, said in a news release. “It had me worried for a while that we were seeing what we wanted to see. Things are almost never exactly as you expect in this field — there are usually surprises around every corner, but theory and observation matched perfectly in this case.”

Astronomers took note of the TRAPPIST-1 system back in February because the star is just 40 light-years from Earth, and because as many as three of its seven planets may be potentially habitable.

Data from the TRAPPIST telescope in Chile made it possible to describe the orbits of the inner six planets in detail, but more readings of planetary transits were required to confirm the orbit of TRAPPIST-1h.

Luger and his colleagues added in data from NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope, which is conducting what’s known as its K2 planet survey. Thanks to the Kepler data, the team determined that the TRAPPIST-1h has an 18.77-day orbit, and that it’s about three-quarters as wide as Earth.

They found that the timing of the seven planets’ orbits were finely tuned in a 2:3:4:6:9:15:24 pattern, a “resonant chain” that can keep the planetary system running like clockwork for billions of years without any crashes.

TRAPPIST-1 is significantly dimmer and cooler than our sun, but its planets orbit significantly closer that any of our solar system’s worlds. That’s what makes it plausible to suggest that liquid water might exist on the fourth, fifth and sixth planets under the right conditions. They orbit in the “Goldilocks Zone,” which just might be not too hot, not too cold, but just right for life.

The newly reported findings confirm that the seventh planet is way too cold. Computer modeling suggests that its average temperature is 148 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. However, it could have been in a much warmer state for a period of several hundred million years when TRAPPIST-1 was younger and brighter.

“We could therefore be looking at a planet that was once habitable and has since frozen over, which is amazing to contemplate and great for follow-up studies,” Luger said.

TRAPPIST-1 and other relatively nearby star systems, such as Proxima Centauri, Alpha Centauri and LHS 1140b, are already on the list of future targets for close-up observations. And there’s a chance that the next generation of telescopes could determine whether the atmospheres of those star systems’ planets contain the chemical signatures of life.

“It’s incredibly exciting that we’re learning more about this planetary system elsewhere, especially about planet h, which we barely had information on until now,” Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s associate administrator for science, said in a news release. “This finding is a great example of how the scientific community is unleashing the power of complementary data from our different missions to make such fascinating discoveries.”

Source: Yahoo.Tech

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.