A 1,500-year-old book that contains a previously unknown gospel has been deciphered.

The ancient manuscript may have been used to provide guidance or encouragement to people seeking help for their problems, according to a researcher who has studied the text.

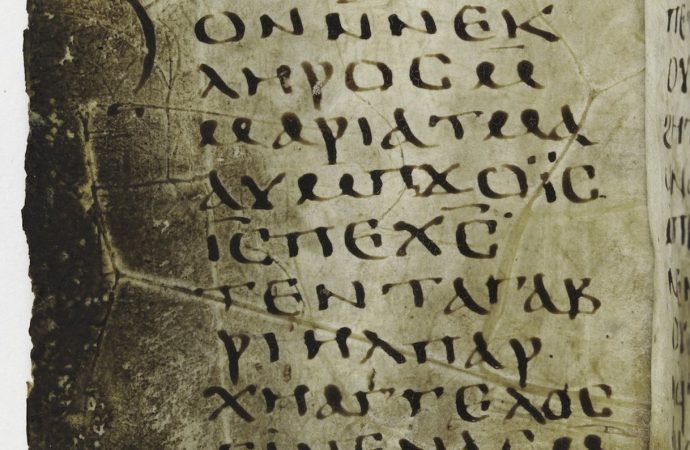

Written in Coptic, an Egyptian language, the opening reads (in translation):

“The Gospel of the lots of Mary, the mother of the Lord Jesus Christ, she to whom Gabriel the Archangel brought the good news. He who will go forward with his whole heart will obtain what he seeks. Only do not be of two minds.”

Anne Marie Luijendijk, a professor of religion at Princeton University, discovered that this newfound gospel is like no other. “When I began deciphering the manuscript and encountered the word ‘gospel’ in the opening line, I expected to read a narrative about the life and death of Jesus as the canonical gospels present, or a collection of sayings similar to the Gospel of Thomas (a non-canonical text),” she wrote in her book “Forbidden Oracles? The Gospel of the Lots of Mary” (Mohr Siebeck, 2014).

What she found instead was a series of 37 oracles, written vaguely, and with only a few that mention Jesus.

The text would have been used for divination, Luijendijk said. A person seeking an answer to a question could have sought out the owner of this book, asked a question, and gone through a process that would randomly select one of the 37 oracles to help find a solution to the person’s problem. The owner of the book could have acted as a diviner, helping to interpret the written oracles, she said.

Alternatively, the text could have been owned by someone who, when confronted with a question, simply opened an oracle at random to seek an answer.

Credit: Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of Mrs. Beatrice Kelekian in memory of her husband, Charles Dikran Kelekian, 1984.669

The 37 oracles are all written vaguely; for instance, oracle seven says, “You know, o human, that you did your utmost again. You did not gain anything but loss, dispute, and war. But if you are patient a little, the matter will prosper through the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.”

Another example is oracle 34, which reads, “Go forward immediately. This is a thing from God. You know that, behold, for many days you are suffering greatly. But it is of no concern to you, because you have come to the haven of victory.”

Throughout the book “the text refers to hardships, suffering and violence, and occasionally one finds a threat. On the whole, however, a positive outlet prevails,” Luijendijk wrote in her book.

Another interesting example, that illustrates the ancient book’s positive outlook, is oracle 24, which reads, “Stop being of two minds, o human, whether this thing will happen or not. Yes, it will happen! Be brave and do not be of two minds. Because it will remain with you a long time and you will receive joy and happiness.”

A ‘gospel’ like no other

In the ancient world, a special type of book, sometimes called a “lot book,” was used to try to predict a person’s future. Luijendijk says that this is the only lot book found so far that calls itself a “gospel” — a word that literally means “good news.”

“The fact that this book is called that way is very significant,” Luijendijk told Live Science in an interview. “To me, it also really indicated that it had something to do [with] how people would consult it and also about being [seen] as good news,” she said. “Nobody who wants to know the future wants to hear bad news in a sense.”

Although people today associate the word “gospel” as being a text that talks about the life of Jesus, people in ancient times may have had a different perspective.

“The fact that this is not a gospel in the traditional sense gives ample reason to inquire about the reception and use of the term ‘gospel’ in Late Antiquity,” Luijendijk wrote.

Where did it come from?

The text is now owned by Harvard University’s Sackler Museum. It was given to Harvard in 1984 by Beatrice Kelekian, who donated it in memory of her husband, Charles Dikran Kelekian. Charles’ father, Dikran Kelekian (1868-1951), was “an influential trader of Coptic antiquaries, deemed the ‘dean of antiquities’ among New York art dealers,” Luijendijk wrote in her book.

It is not known where the Kelekians got the gospel. Luijendijk searched the Kelekian family archive but found no information about where the text came from or when it was acquired.

It’s possible that, in ancient times, the book was used by a diviner at the Shrine of Saint Colluthus in Egypt, a “Christian site of pilgrimage and healing,” Luijendijk wrote. At this shrine, archaeologists have found texts with written questions, indicating that the site was used for various forms of divination.

“Among the services offered to visitors of the shrine were dream incubation, ritual bathing, and both book and ticket divination,” Luijendijk wrote.

Miniature text

One interesting feature of the book is its small size. The pages measure less than 3 inches (75 millimeters) in height and 2.7 inches (68.7 millimeters) in width. The codex is “only as large as my palm,” Luijendijk wrote.

“Given the book’s small size, the handwriting is surprisingly legible and quite elegant,” she wrote. The book’s small size made it portable and, if necessary, easy to conceal. Luijendijk notes that some early church leaders had a negative view of divination and put in place rules discouraging the practice.

Regardless of why its makers made the text so small, the book was heavily used, with ancient thumbprints still visible in the margins. “The manuscript clearly has been used a lot,” Luijendijk said.

Source: Live Science

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.