To hear the Romans tell it, the arrival of Huns at the empire’s border was an unmitigated catastrophe.

“The Huns in multitude break forth with might and wrath … spreading dismay and loss,” read a poem engraved on a wall in ancient Constantinople. “And naught but loss of life and breath their course shall ever stay.”

The nomadic Huns, who ranged across Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia, were called “treacherous,” “scarcely human,” “the scourge of all lands.” Historical accounts, many of them written long after the wars with the Huns were over, blamed them for the fall of Rome and the Dark Ages that followed.

It’s certainly true that the Huns’ military campaign cut the Roman Empire to its core. But Susanne Hakenbeck, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge, was suspicious of accounts by the bitter losers.

“The way they write about them is really cliched,” she said. “They say, ‘they look like animals,’ ‘none of what they do is civilized,’ ‘they’re all terrible.’ And I just thought, how can this be true? There’s so much obvious bias in these sources. What was really going on?”

To answer that question, Hakenbeck went straight to the source: She examined the bones of the Huns themselves.

For a new paper published in the journal PLOS One Wednesday, Hackenbeck studied the remains of roughly 200 people from five 5th-century sites in a Roman frontier region called Pannonia (in what is now Hungary). By examining the ratios of elements contained within the ancient people’s bones and teeth, Hackenbeck and her colleagues could figure out who they were and how they lived.

What the scientists found surprised them. While the Roman and Hunnic elites were at war, regular people living on the margins of these two empires were able to coexist, even cooperate. Bones buried in the same cemetery carried signatures of dramatically different lifestyles — some bore evidence that their owners were farmers, others had traits of nomads. Some bones suggested that the individual was born into a roaming tribe but later settled down; others indicated the opposite lifestyle change.

“There were enormous changes in people’s life circumstances, both in specific individuals and within populations,” Hakenbeck said. “People were doing all sorts of different things, but they all ended up in the same cemetery.”

This suggests that that story of inhuman violence told by Romans is “mostly inappropriate,” Hakenbeck said. “It wasn’t necessarily just a story of conflict, but more a story of cross-border exchanges, cross-border adaptability.”

A map of the sites analyzed by Hakenbeck and her colleagues. (Fred Lewsey/Cambridge University)

Hackenbeck’s analysis relies on the adage, “we are what we eat and drink,” she said. Different diets will leave characteristic signatures in the carbon, nitrogen and strontium isotopes contained inside a person’s bones (elements come in different versions, or isotopes, that differ in mass).

The nomadic Huns subsisted on meat, milk and millet, a tiny grain valued for its adaptability and short growing period, and their remains reflected that. They contained higher ratios of nitrogen 15, which is found in meat, and an isotope of carbon that’s preferred by arid-area grasses like millet. By contrast, agricultural populations ate mostly grains and other plants; their bones contained the form of carbon preferred by fruits, vegetables and wheat.

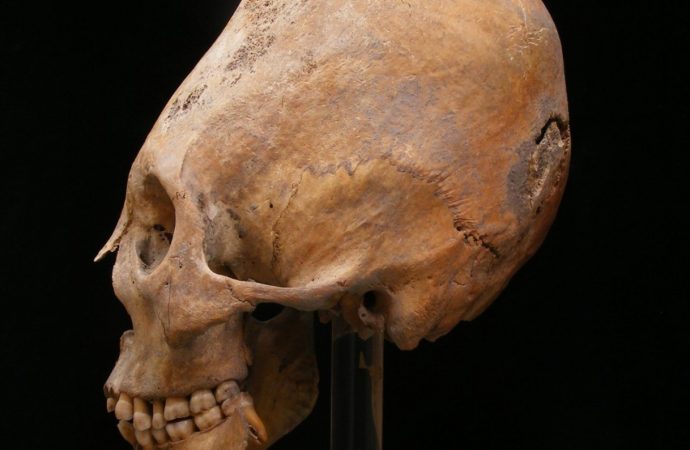

The element strontium, which dissolves in drinking water and gets incorporated into tooth enamel, could also be used to trace individuals to their birthplaces and determine how much they’d traveled since childhood. In addition, some skulls bore evidence of modification — Huns and other ancient people shaped their heads by binding infants’ skulls.

Isotopic analysis of remains from the Pannonian gravesites indicates that these communities were in flux. It appeared that some Huns were attracted to the agricultural lifestyle and settled down. In other cases, farmers seemed to have taken up arms and joined the migrating herdsmen. There are no clear patterns based on sex, skull modifications or accompanying grave goods, Hakenbeck said.

She interprets this as a sign that ordinary people on the frontier, who often faced the same political and economic pressures, continued to swap knowledge and culture even as their leaders fought.

“These were difficult times — there was violence, there was economic instability — and I imagine having recourse to different types of subsistence was a kind of insurance policy,” she said.

Though archaeologists have conducted isotope analyses at sites in Europe, Hakenbeck said she hasn’t heard of anything like this kind of mixing. The Pannonia region was unique, she believes, because it is bisected by rivers (an important mode of transportation) and because its climate was suited to both farming and herding.

She did find one written account of a Roman citizen who took up the Huns’ way of life. A 5th-century Roman emissary to Atilla, the ruler of the Huns, wrote about encountering a former merchant at the conqueror’s court. Apparently the man had been a prisoner but chose to stay with the Huns even after his ransom was paid.

In the Roman’s account, the envoy convinces the merchant to return to his life in the empire, but that could be a politically motivated embellishment, Hakenbeck said. Who knows what happened in real life, or in cases not recorded by historians?

“The thing about isotope analysis is it allows us to get to grips with what ordinary people’s lives were all about,” Hakenbeck said. “This is what, to me, is what makes archaeology so nice: The materials and the scientific methods, they don’t discriminate. They pick up everyone.”

Source: The Washington Post

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.