Frozen beneath a region of cracked and pitted plains on Mars lies about as much water as what’s in Lake Superior, largest of the Great Lakes, a team of scientists led by The University of Texas at Austin has determined using data from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Scientists examined part of Mars’ Utopia Planitia region, in the mid-northern latitudes, with the orbiter’s ground-penetrating Shallow Radar (SHARAD) instrument. Analyses of data from more than 600 overhead passes revealed a deposit more extensive in area than the state of New Mexico. The deposit ranges in thickness from about 260 feet to about 560 feet, with a composition that’s 50 to 85 percent water ice, mixed with dust or larger rocky particles.

At the latitude of this deposit—about halfway from the equator to the pole—water ice cannot persist on the surface of Mars today. It turns into water vapor in the planet’s thin, dry atmosphere. The Utopia deposit is shielded from the atmosphere by a soil covering estimated to be about 3 to 33 feet thick.

“This deposit probably formed as snowfall accumulating into an ice sheet mixed with dust during a period in Mars history when the planet’s axis was more tilted than it is today,” said Cassie Stuurman of the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, a unit of the Jackson School of Geosciences. She is the lead author of a report in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

The name Utopia Planitia translates loosely as the “plains of paradise.” The newly surveyed ice deposit spans latitudes from 39 to 49 degrees within the plains. It represents less than 1 percent of all known water ice on Mars, but it more than doubles the volume of thick, buried ice sheets known in the northern plains. Ice deposits close to the surface are being considered as a resource for astronauts.

“This deposit is probably more accessible than most water ice on Mars, because it is at a relatively low latitude and it lies in a flat, smooth area where landing a spacecraft would be easier than at some of the other areas with buried ice,” said Jack Holt, a research professor at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, and a co-author of the Utopia paper who is a SHARAD co-investigator and has previously used radar to study Martian ice in buried glaciers and the polar caps.

The Utopian water is all frozen now. If there were a melted layer—which would be significant for the possibility of life on Mars—it would have been evident in the radar scans. However, some melting can’t be ruled out during different climate conditions when the planet’s axis was more tilted.

“Where water ice has been around for a long time, we just don’t know whether there could have been enough liquid water at some point for supporting microbial life,” Holt said.

Utopia Planitia is a basin with a diameter of about 2,050 miles, resulting from a major impact early in Mars’ history and subsequently filled. NASA sent the Viking 2 Lander to a site near the center of Utopia in 1976. The portion examined by Stuurman and colleagues lies southwest of that long-silent lander.

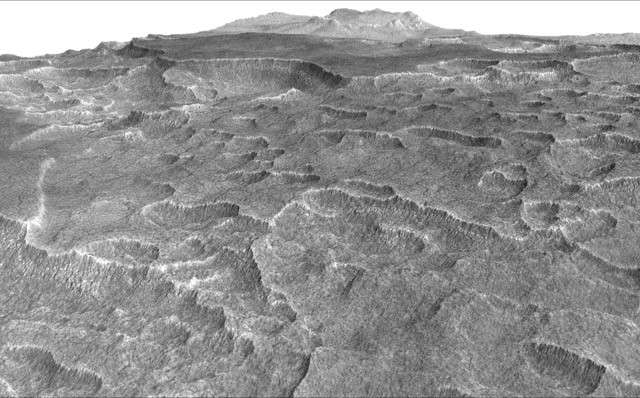

Use of the Italian-built SHARAD instrument for examining part of Utopia Planitia was prompted by Gordon Osinski at Western University in Ontario, Canada, a co-author of the study. For many years, he and other researchers have been intrigued by ground-surface patterns there such as polygonal cracking and rimless pits called scalloped depressions—”like someone took an ice cream scoop to the ground,” said Stuurman, who started this project while a student at Western.

In the Canadian Arctic, similar landforms are indicative of ground ice, Osinski noted, “but there was an outstanding question as to whether any ice was still present at the Martian Utopia or whether it had been lost over the millions of years since the formation of these polygons and depressions.”

The large volume of ice detected with SHARAD advances understanding about Mars’ history and identifies a possible resource for future use.

“It’s important to expand what we know about the distribution and quantity of Martian water,” said Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Deputy Project Scientist Leslie Tamppari of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “We know early Mars had enough liquid water on the surface for rivers and lakes. Where did it go? Much of it left the planet from the top of the atmosphere. Other missions have been examining that process. But there’s also a large quantity that is now underground ice, and we want to keep learning more about that.”

Joe Levy of the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, a co-author of the new study, agreed.

“The ice deposits in Utopia Planitia aren’t just an exploration resource. They’re also one of the most accessible climate change records on Mars,” he said. “We don’t understand fully why ice has built up in some areas of the Martian surface and not in others. Sampling and using this ice with a future mission could help keep astronauts alive, while also helping them unlock the secrets of Martian ice ages.”

The original version of this release was posted on the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory home page.

Source: Phys.org

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.