This will help us better understand how to use the drug for medical purposes

How exactly does marijuana make us high? We’re a little closer to knowing now that scientists have figured out the structure of the brain receptor that interacts with the drug. The discovery will help us understand how to better use marijuana for medical purposes — and solve the mystery of why synthetic marijuana is so dangerous, but nobody dies from the natural stuff.

People get stoned when an ingredient in marijuana called THC binds to a receptor called cannabinoid receptor 1, or CB1. Everyone is interested in CB1 because it holds the answer to big questions about how marijuana works and what it can be used for. Years ago, European officials approved an appetite-suppressing drug called rimonabant that worked by blocking CB1. Problem was, the drug also seemed to cause depression and anxiety, and it was eventually withdrawn. If we understand CB1, we may be able to keep this from happening again.

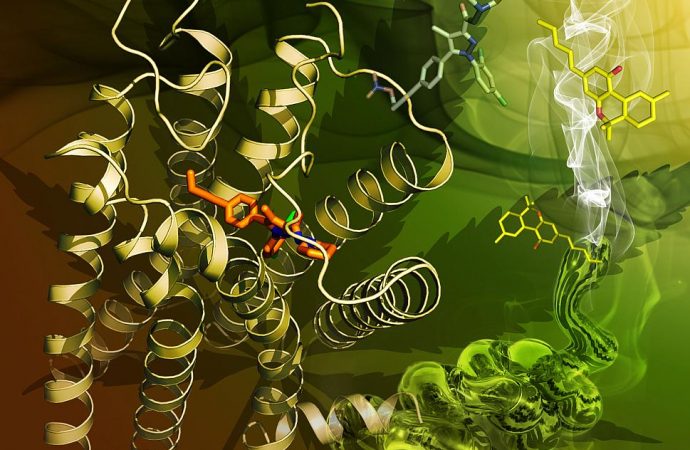

So, scientists developed a special molecule that made the receptor freeze for long enough that they could see its molecular structure, according a study published today in the journal Cell. Then, they did computer simulations to see how THC and other molecules would interact with the receptor. Knowing the structure lays the groundwork for a lot of further research on the marijuana and its side effects.

Imagine the receptor like a switchboard, says study co-author Zhi-Jie Liu, a molecular biologist at ShanghaiTech University. It’s connected to wires that can each cause pain relief, appetite suppression, or depression. If you don’t know how the wiring works, you risk having bad side effects when you tinker with the whole thing. Or you send people to the hospital after they use synthetic marijuana like K2 and Spice. Synthetic marijuana is a bunch of man-made chemicals that interact with CB1. It’s supposed to have the same effect as marijuana, yet it’s far more dangerous. But without knowing how CB1 works, it’s hard to figure out why.

It was very hard to study the CB1 receptor because it moves around too much. All receptors in our bodies are held together by both internal and external forces, says Raymond Stevens, a chemist at the University of Southern California. To study an individual receptor, scientists take it out of the natural environment with various chemicals. But these chemicals can cause the protein to fall apart, which means it’s impossible to see what it looks like. “This receptor was one of the most difficult to study given how unstable the receptor is,” Stevens wrote in an email. This was especially surprising because CB1 is so common.

One breakthrough came when co-author Alexandros Makriyannis developed a molecule that froze CB1 long enough for the scientists to figure out the structure.

And once they figured out the structure, the was one surprise. Receptors have a special place where other molecules can interact with it to turn it on or off; this is called the active site. “What was interesting here is that active site had a lot of crannies, a lot of different sites within it,” says Makriyannis. “We didn’t expect it to be so intricate.” This may be why the receptor was so unstable to begin with, and it also means that lots of different types of molecules can fit within the site. This provides opportunities to design specific molecules and drugs that might, for example, suppress appetite without causing depression.

Finally, the researchers did computer simulations of how CB1 would interact with molecules like THC. Basically, you program the receptor and molecule into the computer and tell it to figure out how the two might fit. These types of simulations are important, says Pal Pacher, a senior investigator at the National Institutes of Health who was not involved in the study. But computer simulations aren’t a replacement for seeing the molecules actually interact, so more studies should be done.

The team has received a grant from the National Institutes of Health to work on directly observing how other molecules might interact with the drug. The next step, says Stevens, is figuring out exactly how the receptor gets turned on and off to study just what makes K2 and Spice so dangerous.

Source: The Verge

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.