The question of why are we here perhaps means different things to different people, but in the field of particle physics it is a question that we may be close to finding an answer to.

Experimental results presented to the 27th International Conference on Neutrino Physics and Astrophysics (Neutrino 2016) last week could explain the tiny differences in matter and anti-matter that allow the Universe to exist.

If we take ourselves back about 13.82 billion years ago the Universe was just being created at the point of the Big Bang. According to our current understanding of physics there was an equal amount of matter and antimatter. But this provides a problem, because when a matter particle meets its antimatter counterpart they disappear leaving behind just a flash of energy.

None of us should therefore be here and in our place there would just be a Universe consisting of nothing but light.

Somehow, one 10 billionth of the matter that was created managed to survive and makes up everything we see around us today.

To explain why this small amount of matter managed to survive physicists have been looking for a tiny difference between matter and antimatter.

The neutrino, a fundamental building block of all that is around us, appears to be showing this difference.

Neutrino Facts

- The neutrino is a fundamental building block of the Universe, it cannot be broken down into further components.

- First suggested in 1930 by Wolfgang Pauli it was first detected in 1955 by Frederick Reines and Clyde Cowan.

- Previously thought to have no mass, neutrinos are the lightest known particle with mass. Their mass is 4 millionths that of an electron.

- The neutrino is the second most abundant known particle. 60 billion neutrinos from the Sun pass through an area the size of your fingernail every second.

- Extremely difficult to measure, neutrinos can easily pass through the Earth without being stopped.

- There are three types, or flavour, of neutrino: the electron-neutrino, the muon-neutrino and the tau-neutrino. Each has an antimatter counterpart.

The subject of the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physics, neutrinos were seen to exist in three different flavours: the electron-neutrino, the muon-neutrino and the tau-neutrino.

As shown in the Nobel Prize winning work neutrinos can have an identity crisis. A single neutrino particle can flip between the flavours, a process known as neutrino oscillations.

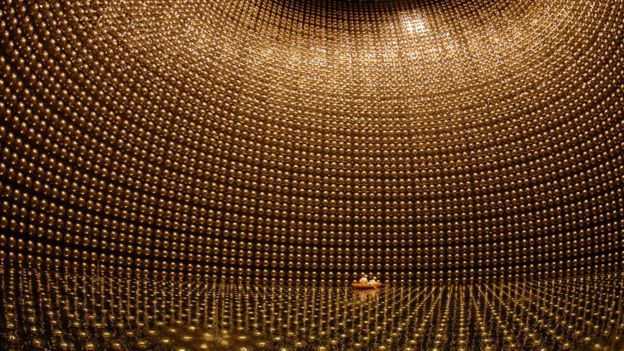

Professor Hirohisa Tanaka of Toronto University and the Tokai to Kamioka (T2K) neutrino experiment in Japan speaking to Science in Action described how T2K is investigating the oscillation process in neutrinos and their anti-matter equivalents. “We are studying this by In Japan using an [particle] accelerator to produce a neutrino of one type and sending it 295 km across Japan to the Super-Kamiokande detector,” he says.

Once the neutrinos reach the detector in the disused Kamioka mine under the mountains of western Japan, Professor Tanaka and the T2K team look to see if any of the particles have changed their flavour.

Professor Tanaka explained that three years ago the observation was made that muon-neutrinos fired across Japan between the two parts of the experiment were turning into electron neutrinos.

In 2014, the team reconfigured the experiment to fire anti-neutrinos. Explaining the results, Professor Tanaka said: “Our first results suggest that somehow the neutrino process [neutrino oscillations] happens more often than the anti-neutrino process.”

This is the first indication that the presumed asymmetry or imbalance between neutrinos and antineutrinos is actually there. Absolute confirmation will, though, require more data.

However greater confidence is provided as a similar experiment NOvA in the United States also reported results at the Neutrino2016 conference that support the same picture.

Source: BBC News

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.