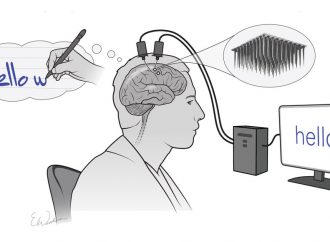

However unlikely contact with aliens may be, scientists are thinking about how they would break the news to a nervous planet.

CREDIT: AARON FOSTER/GETTY IMAGES

CREDIT: AARON FOSTER/GETTY IMAGESDetecting a signal from an extraterrestrial intelligence would be life changing for everyone on Earth – the biggest news story in history – and could potentially be dangerous, especially if badly handled.

Writing in the journal Acta Astronautica, scientists at the Search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI) institute describe a protocol for how to break it to the world that we’re not alone in the Universe – without causing global mayhem.

Rather than a conspiracy of government cover-ups so beloved of sci-fi writes, the study strongly recommends openness as the key to having a “sane global conversation” about the discovery of ET.

Nobody knows how the world would react to the discovery of extraterrestrial intelligence. All we have to go on are the bizarre occurrences where the public thought they were hearing such news.

In 1938 Orson Welles’ radio-play based on HG Wells’s novel The War of the Worlds caused widespread panic in the United States (although the scale of that panic was likely exaggerated). In 1949, a Spanish language version of the same program incited rioting in Ecuador, leading to at least seven deaths, and possibly as many as 20.

Then there’s the risk of the media misreporting or exaggerating the importance of a tentative signal. In October 2015, for example, when a newly discovered extrasolar planet, KIC 8462852, was discovered to show a periodic dip in brightness, the mainstream media latched on to the most speculative, and least likely, explanation – namely that an “alien megastructure” was passing in front of its star. (The periodic dimming is more likely caused by a cloud of comets passing by.)

As a result of these excesses, scientists have been worried about how to break SETI news for decades.

In 1989, the International Academy of Astronautics drew up a set of guidelines for releasing information about a potential alien signal. But that was before the internet and social media transformed the way we consume news stories.

Now, Duncan Forgan and Alexander Scholz, from the University of St Andrew’s in Scotland, have prepared an updated protocol for how scientists should navigate the “unprecedented media onslaught”.

First, Forgan and Scholz advise, all scientists performing a SETI experiment should clearly outline their search methodology as well as define what makes a “discovery”, before the search even begins. This information should be published in a format the media can easily access, such as a blog post.

Then if a signal is detected, the discoverers should not to try to keep it under wraps – the potential fall-out from a leak would be too damaging. Much better to announce a tentative detection, but be clear that it must be assumed to be of natural or manmade origin until proved otherwise.

The scientists should submit their findings to a peer-reviewed journal, while simultaneously uploading all data so it can be pored over by other scientists – and potential known sources ruled out.

The problem is these verifications can take a long time. The best case-study is the so-called “Wow” signal, detected in 1977. That signal was exactly what SETI scientists had been looking for – being at the right frequency to hold an interstellar conversation, and being of unprecedented strength – and is still unexplained almost 39 years later. (Although in early 2016, a study published by the Washington Academy of Sciences suggested that comets could emit such a signal, and identified two comets that were in the right place at the right time in 1977. Future measurements of radio emission by comets should hopefully clear this up.)

In the case where the detection cannot be confirmed, say Forgan and Scholz, the SETI scientists should publish an announcement saying so.

In the case of the detection is confirmed, however, the SETI scientists should become deeply involved in the global conversation by engaging across as many social media platforms as possible – a role they would likely assume for the rest of their lives. They should also be prepared for the downsides of newfound fame – such as cyber attacks.

The latest polls (conducted in Germany, the UK and US last September) show that most people in developed countries believe intelligent aliens exist somewhere in the Universe. But that doesn’t mean we’re ready for a “first contact” event.

However unlikely such a discovery is, a signal from an alien intelligence would be the most momentous discovery the human species is ever likely to make. It’s worth a little thinking ahead.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.